The total number of people living in poverty in Mexico continues to rise, though the poverty rate (as a percentage) remains roughly the same. According to Mexico’s National Political and Social Development Commission (Spanish language acronym: Coneval), the number of people in poverty has risen steadily for several years, much in line with Mexico’s rising total population. Coneval’s figures are based on a simple multidimensional poverty index, which considers the following criteria:

- household income

- access to education

- access to food

- access to health care

- access to social services

- housing quality

- access to basic household services (electricity, water, drainage)

According to Coneval, 53.3 million Mexicans (45.5% of the total population) were living in poverty in 2012, compared to 52.8 million (46.1% of the then population) in 2010 and 48.8 million Mexicans (44.5%of the population) in 2008.

Note that poverty statistics prior to 2008 in Mexico were generally based purely on income levels. From 2008, this method was replaced by a multidimensional index. The precise details of the index have been modified slightly since that time, making exact comparisons between 2012 and 2008 more problematic.

While the precise numbers are subject to debate, mainly due to differing definitions of what constitutes “poverty” and how it can be measured, the trend revealed by the Coneval numbers is supported by the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC) in its “Social Panorama of Latin America 2013“, published in December 2013. The ECLAC report found that Mexico is one of a very few countries where poverty levels rose between 2011 and 2012, from 36.3% of the population to 37.1%, according to its definition.

The dire situation in Mexico compares to a slight decrease in poverty in most larger Latin American countries, including Venezuela, Ecuador, Brazil, Peru, Argentina and Colombia.

In absolute terms, according to ECLAC, 164 million people were found to be living in poverty in Latin America, about 57.4 million (35%) of them in Mexico.

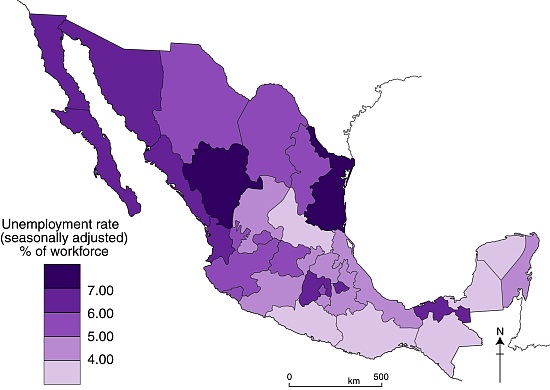

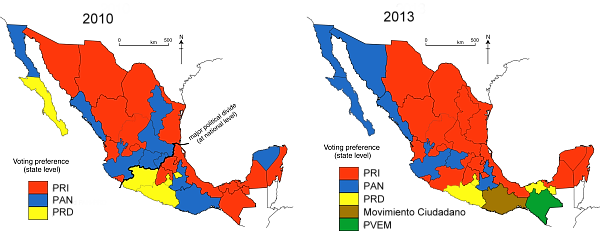

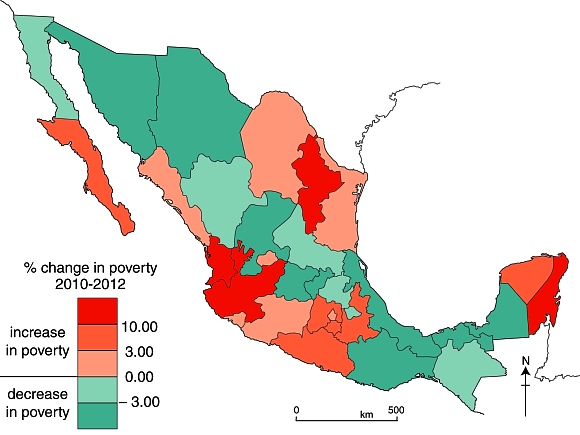

Change in poverty rates in Mexico, 2010-2012. Credit: Geo-Mexico; all rights reserved. Data: Coneval

The map shows the Coneval data for changes in the poverty rate between 2010 and 2012 by state. It appears that poverty levels increased in many of Mexico’s more prosperous areas and in the longer established industrial areas, as well as in almost all areas where tourism is important. Poverty decreased in some of Mexico’s more rural, and generally poorer, states.

Related posts:

- Mexico’s richest individuals in 2010 (Mar 2010)

- The widening income gap in Mexico; the rich earn 26 times more than the poor (Dec 2011)

- Trends in income distribution in Mexico: are the poor getting poorer? (Feb 2011)

- The GINI index: is inequality in Mexico increasing? (Oct 2011)

- Is poverty in Mexico on the rise? (Sep 2011)

- The measurement of poverty: the Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI) (Sep 2011)

- The disparities in Mexico between indigenous peoples and the remainder of the population (Apr 2010)

- J.K. Galbraith talks about Mexico’s poverty and inequality (Aug 2012)

- Mexico receives $280m in international funding to fight urban poverty (Oct 2011)

- The Ethos Foundation’s Multidimensional Poverty Index (Sep 2011)