Many common garden flowers were developed from samples collected in Mexico by a German botanist financed by Britain’s Horticultural Society.

Karl Theodor Hartweg (1812-1871) came from a long line of gardeners and had gardening in his genes. Born in Karlsruhe, Germany, he worked in Paris, at the Jardin des Plantes, before moving to England to work in the U.K. Horticultural Society’s Chiswick gardens in London. Keen to travel even further afield, he was appointed an official plant hunter and sent to the Americas for the first time in 1836. What was originally intended to be a three-year project eventually became an expedition lasting seven years.

By Hartweg’s time, Europeans already knew that Mexico was a veritable botanical treasure trove, full of exciting new plants. For example, the humble dahlia, a Mexican native since elevated to the status of the nation’s official flower, had already become very prominent in Europe. Mexican cacti were also beginning to acquire popularity in Europe at this time.

The Horticultural Society saw both academic and financial potential in sponsoring Hartweg to explore remote areas of Mexico, and collect plants that might flourish in temperature climes such as north-west Europe.

Fuchsia fulgens

Hartweg proved to be an especially determined traveler, who covered a vast territory in search of new plants. He collected representative samples and seeds of hundreds and hundreds of species, many of which had not previously been scientifically named or described. Orchids from the Americas were particularly popular in Hartweg’s day. According to Merle Reinkka, the author of A History of the Orchid, Hartweg amassed “the most variable and comprehensive collection of New World Orchids made by a single individual in the first half of the [19th] century”.

Shortly after arriving in Veracruz in 1836, Hartweg met a fellow botanist, Carl Sartorius (1796-1872), of German extraction, who had acquired the nearby hacienda of El Mirador a decade earlier. Sartorius collected plants for the Berlin Botanical Gardens. His hacienda, producing sugar-cane, set in the coastal, tropical lowlands, became the mecca of nineteenth century botanists visiting Mexico.

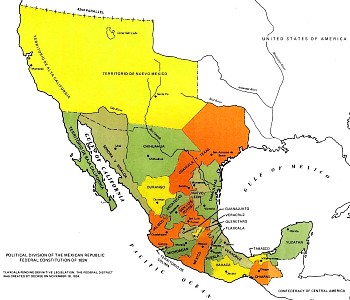

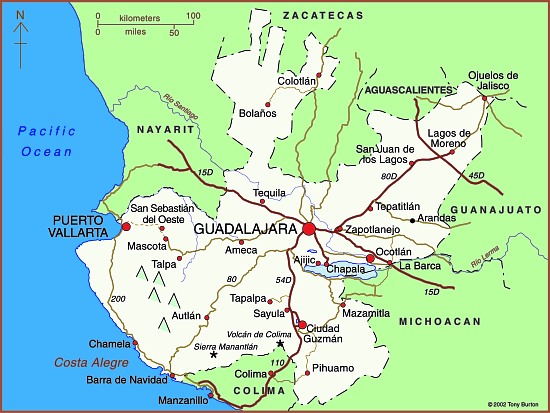

From 1836 to 1839, Hartweg explored Mexico, criss-crossing the country from Veracruz to León, Lagos de Moreno and Aguascalientes before entering the rugged landscapes around the mining town of Bolaños in early October 1837. In his own words, reaching Bolaños had involved “travelling over a mountain path of which I never saw the like before”, one “which became daily work by the continual heavy rains.” From Bolaños, Hartweg visited Zacatecas, San Luis Potosí (in February 1838) and Guadalajara, where he did not omit to include a detailed description of tequila making. From Guadalajara, he moved on to Morelia, Angangueo [then an important mining town, now the closest town of any size to the Monarch butterfly reserves], Real del Monte, and Mexico City, from where he sent a large consignment of plant material back to England. Hartweg then headed south to Oaxaca and Chiapas en route to Guatemala, Ecuador, Peru and Jamaica. He arrived back in Europe in 1843.

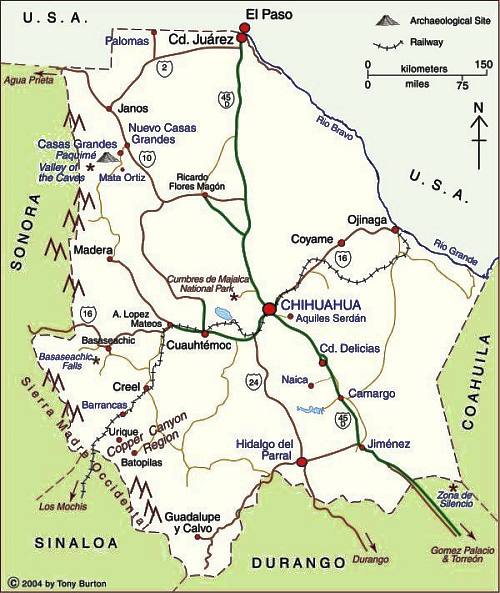

Hartweg visited Mexico again in 1845-46. After arriving in Veracruz in November 1845, he traversed the country via Mexico City (early December) to Tepic, where he arrived on New Year’s Day 1846, to wait for news of a suitable vessel arriving in the nearby port of San Blas which could take him north to California. In the event he had to wait until May, so he occupied himself in the meantime with numerous botanical explorations in the vicinity, including trips to Ceboruco Volcano. From California, he sent further boxes of specimens back to England, including numerous plants which would subsequently become much prized garden ornamentals. During this trip, he also added several new conifers to the growing list found in Mexico. It is now known that Mexico has more of the world’s 90+ species of pine (Pinus) than any other country on earth. This has led botanists to suppose that it is the original birthplace of the entire genus.

It took several years for the boxes and boxes of material sent back to England by Hartweg to be properly examined, cataloged and described. Many of the samples from his early trip were first described formally by George Bentham in Plantae Hartwegianae, which appeared as a series of publications from 1839 to 1842. Among the exciting discoveries were new species of conifers, such as Pinus hartwegii, Pinus ayacahuite, P. moctezumae, P. patula, Cupressus macrocarpa, and Sequoia sempervirens. Hartweg’s collecting prowess is remembered today in the name given to a spectacular purple-flowering orchid, Hartwegia purpurea, which is native to southern Mexico.

Numerous garden plants derive directly from plants Hartweg sent back to Europe. These included Salvia patens (a blue flowering member of the mint family) which became the ancestor of modern bedding salvias, the red-flowering Fuchsia fulgens, ancestor of a very large number of Fuchsia cultivars, and the red-flowering Zauschneria californica, commonly known as California fuchsia.

Original article on MexConnect

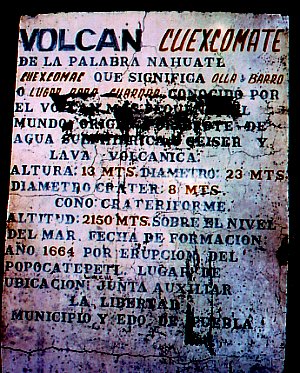

Let’s hope that never happens. It would bring an end to one of the more unusual tourist attractions in this part of Mexico. Climbing down a spiral staircase into claustrophobic darkness is hardly an everyday experience for a tourist, or indeed for a vulcanologist. The crater is about eight meters across. Inside there is, frankly, not much to see apart from the inevitable lava!

Let’s hope that never happens. It would bring an end to one of the more unusual tourist attractions in this part of Mexico. Climbing down a spiral staircase into claustrophobic darkness is hardly an everyday experience for a tourist, or indeed for a vulcanologist. The crater is about eight meters across. Inside there is, frankly, not much to see apart from the inevitable lava!

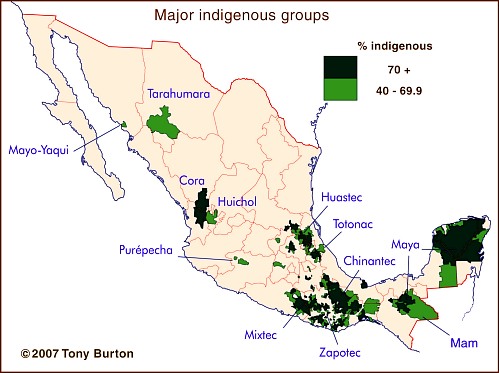

From 1950-1970, the Mexican government opted for a modernization approach, building roads (including the Pan-American highway) and attempting to upgrade agricultural techniques. The mainstay of the regional economy is coffee. During this period, most Mam were peasant farmers, subsisting on corn and potatoes, gaining a meager income by working, at least seasonally, on coffee plantations. Working conditions were deplorable, likened in one report to “concentration camps”. Plantation owners forced many into indebtedness. The Mam refer to this period as the time of the “purple disease”:

From 1950-1970, the Mexican government opted for a modernization approach, building roads (including the Pan-American highway) and attempting to upgrade agricultural techniques. The mainstay of the regional economy is coffee. During this period, most Mam were peasant farmers, subsisting on corn and potatoes, gaining a meager income by working, at least seasonally, on coffee plantations. Working conditions were deplorable, likened in one report to “concentration camps”. Plantation owners forced many into indebtedness. The Mam refer to this period as the time of the “purple disease”: