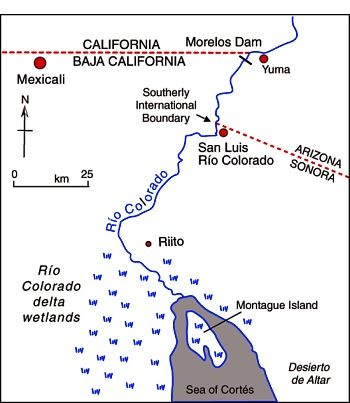

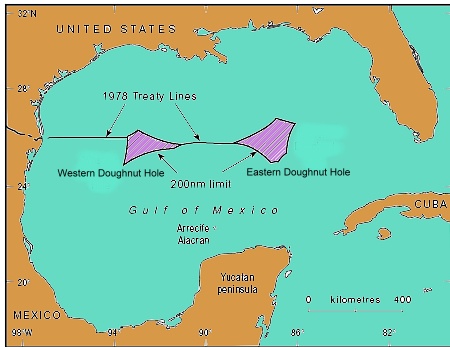

The USA and Mexico share the Gulf of Mexico, with periodic arguments about the precise offshore limits of each country’s jurisdiction. An earlier post includes a brief summary of the history of negotiations over this contentious maritime boundary:

The reason this boundary matters is because the deep waters of the Gulf of Mexico are thought to have massive deep-water oil and gas fields. The USA has encouraged major oil multinationals such as Shell and BP to explore relatively deep parts of the Gulf, those lying more than 500 meters or 1,640 feet below sea level.

Developing these fields requires advanced, specialist deep-water drilling techniques, which only a small number of major international (multinational) oil firms currently have the expertise to undertake. As was seen not long ago, accidents in these fields can be very difficult to avoid and any resulting damage very difficult to clean up:

Developing these fields requires advanced, specialist deep-water drilling techniques, which only a small number of major international (multinational) oil firms currently have the expertise to undertake. As was seen not long ago, accidents in these fields can be very difficult to avoid and any resulting damage very difficult to clean up:

The legal battle connected to that spill has been postponed; it had been due to start today (27 February 2012) in a New Orleans court. The April 2010 accident killed 11 oil workers and released up to 5 million barrels of oil into the Gulf.

In the Mexican sections of the Gulf of Mexico, very little oil exploration and development has yet been carried out. All oil exploration and development in Mexico is managed by state-owned oil giant Petroleos Mexicanos (Pemex), though they can contract other firms to undertake work on their behalf if or when needed. Pemex is the world’s third-largest oil producer and the largest contributor to Mexico’s federal budget. It is one of the very few oil companies worldwide that manages all aspects of the productive chain, from exploration to refining and marketing. Pemex has had more than its fair share of serious environmental issues:

Mexican experts believe that up to 29.5 billion barrels of oil might reside in Mexico’s share of the Gulf, but Pemex has little to show for almost a decade of deep-water drilling apart from some relatively minor gas finds.

A few days ago, Mexico and the USA finally signed an accord that, in the words of Mexican President Felipe Calderón, “ensures that each country can develop its corresponding oil and natural gas deposits in the trans-border area of the Gulf of Mexico.” In a joint formal statement, Mexico’s Foreign Affairs and Energy Secretariats said that the “historic” agreement “will generate the necessary legal certainty for the long-term development of resources that may be found in that area.” It remains to be seen just how quickly and efficiently Pemex can actually take advantage of the deep-water drilling opportunities that the new agreement is designed to safeguard.

Related posts: