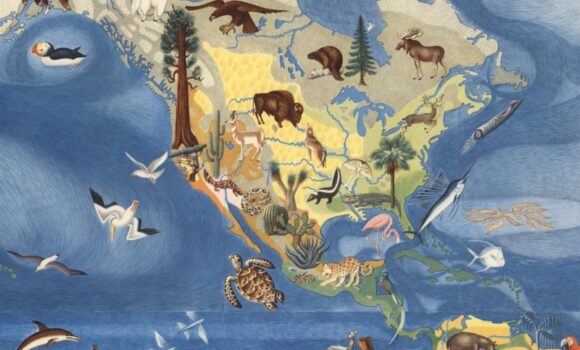

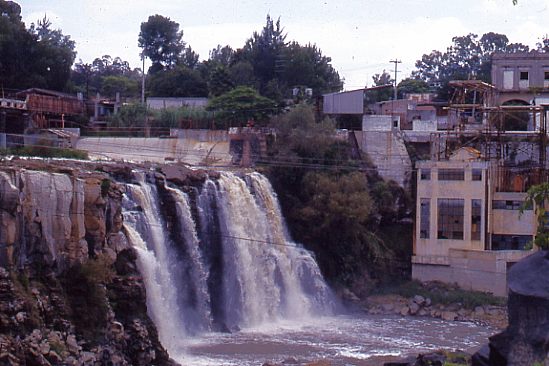

Ecotourism at La Ventanilla on the coast of Oaxaca, a small community of about 100 inhabitants, located between the beach resorts of Puerto Escondido and Puerto Angel, began more than twenty years ago. It is based on trips run by local guides through the mangroves lining a lagoon on the Tonameca River; the area’s wildlife includes iguanas, birds, crocodiles and sea turtles.

The main local cooperative that conducts tours is called Servicio Ecoturisticos de La Ventanilla (La Ventanilla Ecotourism Services). Income from its tours supports reforestation and other ecological projects, including a greenhouse for mangrove reforestation and a nursery to hatch and raise crocodiles for release on Uma Island, in the lagoon. A breakaway co-operative, Cooperativa Lagarto Real, also runs some local excursions, though its profits do not contribute to local conservation efforts.

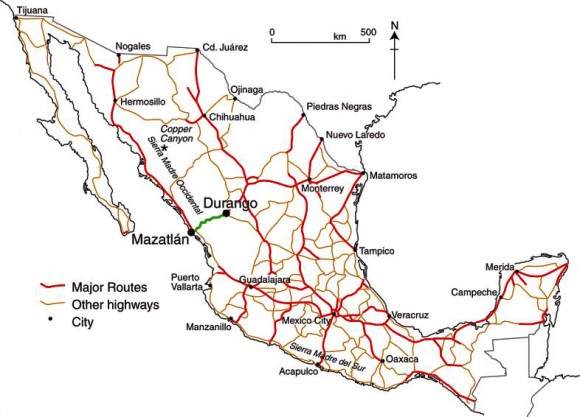

La Ventanilla (Google Earth)

Most visitors to La Ventanilla come only for the day; the small local community offers only limited services or accommodations for tourists. The community of La Ventanilla is often held up as a shining example of how a well-implemented “assistive conservation” ecotourism approach can combine environmental conservation with economic sustainability, while enhancing the local quality of life.

But is this apparent success story quite as idyllic as usually portrayed in the mainstream press? Dr. David Vargas-del-Río, a researcher at ITESO in Guadalajara, sets out to explore this question in his recent article, “The assistive conservation approach for community-based lands: the case of La Ventanilla”, published in the December 2014 issue of The Geographical Journal. The article is based on Vargas-del-Río’s doctorate thesis at the UPC University, Barcelona.

As Vargas-del-Río explains, “The assistive conservation approach includes strategies for conserving community-based lands based on a complex combination of traditional and modern scientific knowledge. It enjoys broad legitimacy and seems promising for conserving territories with autochthonous populations. However, as a novel strategy, it has been applied mostly to societies and environments that are fragile in conservationist terms.”

The author explores how there has been a gradual shift in the protection of natural areas from ‘top-down’ to ‘bottom-up’ models of environmental management, before turning to his case-study of La Ventanilla. La Ventanilla lends itself to such a case study since an assistive conservation approach was first implemented there more than twenty years ago, More than sufficient time to allow for some follow-up evaluation. His eventual conclusion is that while assistive conservation approaches sound good in theory, they may, over time, make local ecologies “more vulnerable to social and environmental degradation, especially as traditional management institutions once responsible for ecological integrity become obsolete”.

In reviewing the background literature, Vargas-del-Río asserts that there are “three broad critical currents” of criticism of the assistive conservation approach. These include the potential adverse impacts of utilizing protected areas for tourism. The provision of attractions, installations and other services, leads to “new dynamics, impacts and transformations” in terms of tourism providers, and may result in “competition between local actors and powerful tourism agents, both conventional and emergent.” Potential issues include changes in local consumption and behavior patterns, and the view that nature and local culture are commodities.

Just how was this manifested in the context of La Ventanilla?

Initial effects of the assistive conservation approach in La Ventanilla were positive. Restrictions were placed, and enforced, on “activities considered ‘disruptive’; that is, hunting, selling local species, harvesting turtle eggs, and felling mangrove trees…”The cooperative soon won praise for its environmental responsibility and received more funds from the government to conduct volunteer conservation projects, including reforestation in the mangroves, a deer reserve, a turtle egg nursery, and areas for iguanas, among other initiatives. Hence, it continued to receive financial and moral power which it exercised over the rest of the population, while promoting conservation and tourism over traditional uses.”

Following extensive fieldwork in the community, Vargas-del-Río found, “a marked tendency towards spatial segregation, social fragmentation, inequality and speculation; phenomena that have emerged as a direct result of the ‘conservation’ initiative with its nature-based tourism activities and imposed environmental restrictions.”The La Ventanilla Ecotourism Services Cooperative (CSELV) is “controlled by six local leaders who own the lands where the cooperative’s main assets are located, handle all accounts, and elaborate support and funding applications.” Other members of the co-operative are “simple wage earners”.

Inequality triggered by the project led to segregation, in terms of housing quality, in the central area of the community. A group of nine disgruntled members of the initial co-operative, broke away in 2004 and founded a second co-operative, Lagarto Real. They “disregarded the management plan”, “sabotaged some conservation and ecotourism initiatives undertaken in this sub-zone, and set up restaurants, shops and camping sites of their own that lacked the ‘green’ image that others were marketing.” The growth of ecotourism has led to land speculation, including a controversy over the construction and (illegal) sale of a small hotel built on communal property.

The island of Uma is controlled by the original co-operative and no longer accessible for traditional activities such as agriculture. There has been a dramatic shift in economic activities. “Agriculture and fishing are now practiced by just 7% of inhabitants and represent an important source of income for only 10.7% of households. In contrast, tourism-related activities occupy 34.7% of the people, represent 70.1% of the economically active population, and are the main source of income for 67.9% of households.”

Vargas-del-Río concludes that previous assessments failed “to take into account slow, gradual changes”. One outcome has been “a higher risk of land degradation in social and environmental terms as the local society fragments, inequality increases, more actors (external and local) strive to profit from the territory, and regulation becomes more difficult.”

In conclusion, “assistive approaches modify ways of approaching nature, restrict traditional uses in favour of tourism, weaken local management institutions and degrade environmental and social relations.” The assistive approach “undermines the cultural, economic and local environment while creating new spaces for consumption.”

Source:

David Vargas-del-Río, 2014. “The assistive conservation approach for community-based lands: the case of La Ventanilla”, The Geographical Journal, Vol. 180 #4 (December 2014) 377–391.

Related posts: