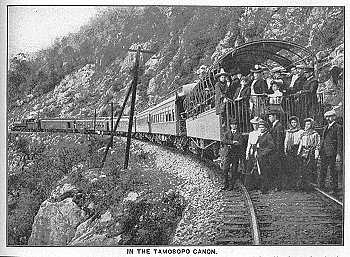

As mentioned in a previous post about tourist guidebooks, the introduction of railways into Mexico and the gradual expansion of the railway network encouraged the development of all kinds of social, industrial and tourist activities.

The Mexico City-Puebla line was completed in 1886 and went via the small town of Cuautla in the state of Morelos. Cuautla is about 25 kilometers south-east of Cuernavaca.

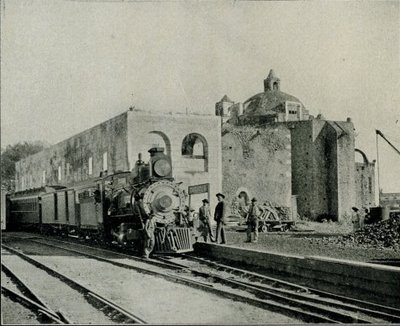

In Cuautla, the builders of the railway found a perfect location for the town’s new station, very close to the center. They station was constructed around the cloisters of an abandoned building, the former Dominican convent of San Diego, which dated back to 1657. Its ecclesiastical life ended some years before parts of it were incorporated into the railway station in 1881.

The 1899 edition of Reau Campbell’s famous Guide provides an idea of what visitors to Cuautla could expect when the train was in its heyday:

The train stops some minutes in Cuautla and there may be time for a walk through the little alameda, just outside of the station, where there are trees and flowers, a hotel where there are good wines, coffee and lunches to be had. As the approach to the station has been through a grove of tropical trees and gardens, so is its departure, and the train continues southward through the cane country to Yautepec…

A decade later, the British-born journalist William English Carson (1870-1940) spent four months in Mexico. Carson also visited Cuautla:

It is a quaint, old-fashioned place, with narrow, cobble-paved streets, and houses of the usual low, flat-roofed type. As I strolled about the town the next morning, I noticed some unusually amusing signs of Americanization. An enterprising barber, for example, displayed a big signboard with the English inscription, “Hygienic, non-cutting barber shop,” as a tempting inducement to tourists, and one or two other establishments displayed in their windows the interesting announcement, “American spoke here.”

The Oldest Railway Station in the World. Cuautla. Inter-Oceanic Railway (from Carson).

Carson also describes the railway station:

Cuautla is also famous for having the oldest railway station in the world, the crumbling, ancient structure which is now used for this purpose having been the Church of San Diego built in 1657. … The day after my arrival I went into the old church, the body of which is now used as a warehouse, while one side of it bordering the railway line provides accommodation for the waiting-room and various offices. A quantity of wine-barrels were piled up at the spot where the high altar had formerly stood, and all kinds of merchandise were stored in other parts of the building. Over the door was an inscription, the first words of which seem appropriate enough to the present condition of the once sacred edifice: “Terribilis est iste hic domus dei et porta coeli ” (How dreadful is this place. This is none other but the house of God and this is the gate of heaven).

In October 1973, the original narrow gauge track from Mexico City to Cuautla was replaced with standard gauge line, bringing a premature end to the lives of several steam engines. These engines were among the very last steam locomotives used in regular service anywhere in North America. Fortunately, the oldest section of narrow gauge in Mexico, built between Amecameca and Cuautla still survives. Originally built in 1881 as the Ferrocarril Morelos (Morelos Railroad), it was partially re-opened, between Cuautla and Yecapiztla, for a tourist steam train service in July 1986, using engine #279 and four restored second class coaches. Engine 279 is a Baldwin locomotive, built in Philadelphia, first brought into service in 1904, and now spends most of its time resting contentedly in the Cuautla museum, the museum that is housed in the oldest building ever used as a railway station anywhere in the world.

Postscript: The rival claims of Red Hall, Bourne, U.K. to be the oldest station building in the world

I am very grateful to Tony Smedley and Ian Jolly, two very alert railway enthusiasts from the U.K., for bringing to my attention the rival claims of a railway station building in Lincolnshire to be the oldest in the world. The original owner of Red Hall, in Bourne, died in 1633. The Hall was later used as the Station Master’s house and Ticket office for the Bourne & Essendine Railway, which began operations in 1860. The last passenger train through Bourne station was apparently in 1959, with freight services ending a few years later. (For more details, click on Red Hall and Bourne Railway Station respectively.

Since the Red Hall (Bourne) station no longer has any rail tracks or trains associated with it, I stand by my claim (for now at least) that Cuautla station (which still does have rail tracks and trains) is the oldest railway station in the world. Apparently, Carson, at the time he was writing, was unaware of the rival claims of Red Hall.

Sources:

Campbell, Reau. Campbell’s New Revised Complete Guide and Descriptive Book of Mexico. Chicago. 1899.

Carson, William English. Mexico: the wonderland of the south. 1909

This is an edited version of an article originally published on MexConnect.

Click here for the complete article

The growth of the railway network and the importance of railways in Mexico are examined in depth in chapter 17 of Geo-Mexico: the geography and dynamics of modern Mexico and tourism in Mexico is the subject of chapter 19.

The Spanish conquistadors found the Aztec roads completely unsuitable for horse traffic and animal-drawn carts. They were forced to undertake expensive re-routing, flattening, widening, and upgrading. In 1550, they started construction of the first section of El Camino Real (the royal highway) linking Mexico City with Spain through the port of Veracruz. The opening of this new road greatly facilitated communication and the transfer of Aztec gold to Spain, and Spanish goods to Mexico’s interior. To counter the threat of bandits, the road was constantly patrolled by soldiers.

The Spanish conquistadors found the Aztec roads completely unsuitable for horse traffic and animal-drawn carts. They were forced to undertake expensive re-routing, flattening, widening, and upgrading. In 1550, they started construction of the first section of El Camino Real (the royal highway) linking Mexico City with Spain through the port of Veracruz. The opening of this new road greatly facilitated communication and the transfer of Aztec gold to Spain, and Spanish goods to Mexico’s interior. To counter the threat of bandits, the road was constantly patrolled by soldiers.