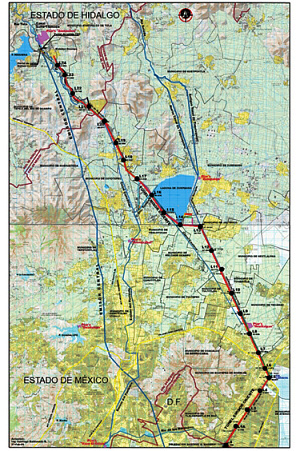

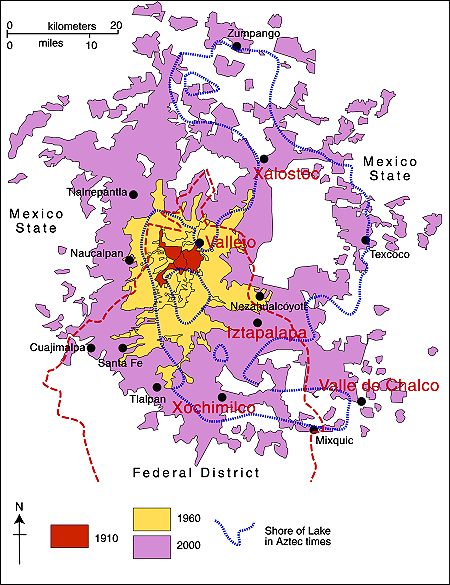

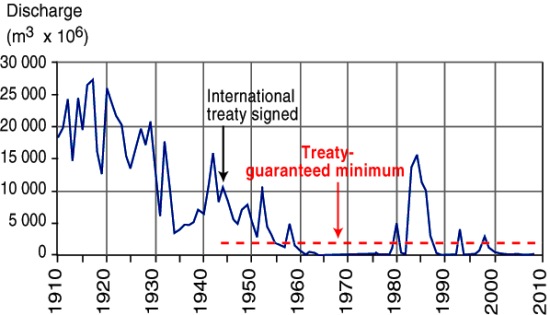

A recent report from researchers at the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM) and the Metropolitan Autonomous University (UAM) confirms that the height of the water table below Mexico City is dropping by about one meter a year, as more water is pumped out of the aquifer than the natural replenishment rate from rainfall. About 60% of Mexico City’s drinking water comes from wells, with the remainder piped into the city, mainly via the Cutzamala system. The researchers say that up to 65% more water is taken from some parts of the Mexico City aquifer than the amount replaced each year by natural recharge.

As we reported in a previous post – Why are some parts of Mexico City sinking into the old lakebed? – this has resulted in parts of Mexico City sinking more than seven meters (23 ft) since 1891, with implications for water pipelines, drainage systems, building foundations and the city’s metro network, as well as an increased incidence of ground subsidence.

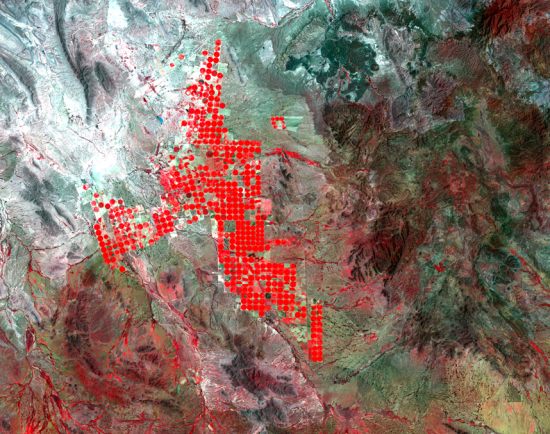

According to this latest research, the clay soil of the former lake bed below the city is sinking by between 6 and 28 cm/yr in most places, with rates in the southeast part of the city (where numerous wells have been drilled in recent years) sinking by up to 35 cm/yr.

How can the problem of sinking ground be resolved?

The report emphasizes the importance of conserving as much green space as possible within the city, to reduce runoff (and demands on the city’s drainage system) while simultaneously recharging aquifers. The three major alternatives, some combination of which is needed to resolve the problem are:

- introduce more water-saving strategies so that demand does not continue to increase

- bring more water from outside the Valley of Mexico (this would be costly and unpopular)

- feed more wastewater back into the underground aquifers via “surface soaks”. As one example, the National Water Commission (Conagua) has announced plans to build a 200-million-dollar wastewater treatment plant (“El Caracol”) that will inject water back into the aquifer after treatment. It would be Mexico’s first ever large-scale reinjection project.

Perhaps not surprisingly, Mexico City residents pay more for their water than users anywhere else in the country, with an average water rate of US$1.23/cubic meter. Elsewhere, the two states sharing the arid Baja California Peninsula also have higher than average rates of $1.05/cubic meter (Baja California Sur) and $0.94/cubic meter (Baja California). The lowest rate in the country, well below the true cost of supplying water, is in Nayarit, and is just $0.25/cubic meter.

Within Mexico City, access to potable water is far from equally/fairly distributed across the city, as revealed by this thought-provoking quote :

In a study of water access in Mexico City, geographer Erik Swyngedouw found that “60 per cent of all urban potable water is distributed to three per cent of the households, whereas 50 per cent of the inhabitants make do on five per cent of the water”. Critical geographers like Swyngedouw ask us to take note of the spatial nature of power imbalances revealed in patterns of city design and growth: “mechanisms of exclusion… manifest the power relationships through which the geography of cities is shaped and transformed.” [quote comes from page 31 of Nature’s Revenge: Reclaiming Sustainability in an Age of Corporate Globalization ; the reference is to Erik Swyngedouw’s Social Power and the Urbanization of Water: Flows of Power (OUP 2004).]

This grossly unequal distribution of potable water remains a critical problem that successive administrations in Mexico City and the surrounding State of México have done little to resolve.

Related posts:

- Why are some parts of Mexico City sinking into the old lakebed?

- More ground cracks appearing in Mexico City and the Valley of Mexico

- Subsidence incident leads to demolition of 31 homes in the State of Mexico

- Attempts to provide drainage for Mexico City date back to Aztec times

- The Eastern Drainage Tunnel: a solution to Mexico City’s drainage problems?

- Mexico D.F. administration offers amnesty to illegal water users

- The challenge of building and maintaining Mexico City’s metro system