Beer was introduced to New Spain by the Spanish. The first permit to produce beer in New Spain was awarded by Spain’s King Charles V to Alonso Herrera in 1544.

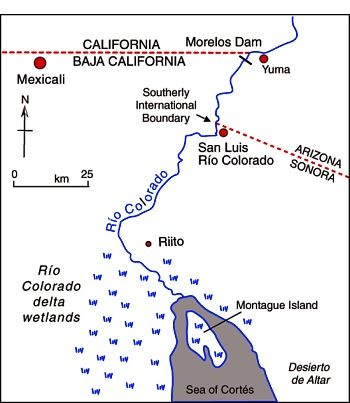

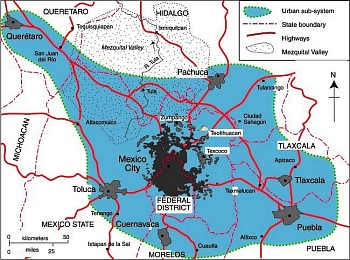

Initially, beer was a pleasure of the upper classes, and a series of local beer shops supplied their needs. During the 17th and 18th centuries, the status of beer changed and it gradually gained popularity among other social classes. Prior to the 20th century, the main breweries were in major urban centers such as Mexico City and Puebla. (Puebla was Mexico’s second largest city until 1870 when it was replaced by Guadalajara).

The relative difficulty of transportation links meant that a single brewery could only serve a limited area. Only after the major railways were built in the last quarter of the 19th century, was it possible for a brewery to ship beer further afield. This same period saw significant foreign investment in breweries, primarily from Germany. Technological improvements enabled the breweries to expand production, industrialize more processes and meet the needs of the ever-growing population. The commercial manufacture and distribution of ice also helped the beer producers. Foreign investment, from the USA and Europe, continued to develop the beer industry until the Mexican Revolution began in 1910.

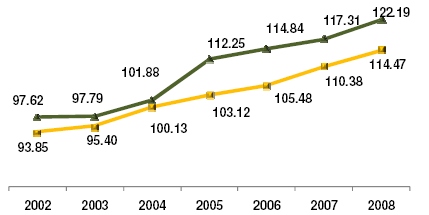

During the 20th century, two major brewery companies emerged, expanding by a combination of building new breweries and acquiring existing ones to bring more and more of the nation into their market areas. These two brewery groups are Grupo Modelo (main brands: Corona, Modelo Especial, Negra Modelo, Pacífico, Victoria, Estrellita, León) and Femsa (Fomento Mexicano; main brands: Tecate, Carta Blanca, Superior, Sol, Indio, Bohemia, Dos Equis, Noche Buena). Between them the control about 80% of the market.

Grupo Modelo

Grupo Modelo currently has a brewing capacity (7 breweries) of 60 million hectoliters. Its new brewery in Nava (Coahuila) will add another 10 million hectoliters to this figure. Modelo started exporting beer (to the USA) in the 1930s. It now exports to more than 150 countries worldwide. It is the world’s 6th largest brewer, accounting for 63% of the combined export and domestic Mexican market.

The granddaughter of the founder of Grupo Modelo is María Asunción Aramburuzabala, whose net worth of $2 billion makes her the richest woman in Mexico.

Femsa

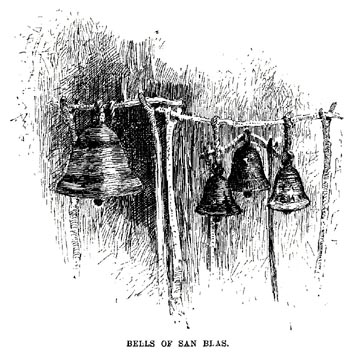

Femsa is the oldest major beer-maker in Mexico. Its brewery division started life in the northern city of Monterrey in 1890 as the Cuauhtemoc Moctezuma brewery (see photo). Femsa brews about 31 million hectoliters of beer a year, including three of the top 5 beer brands in Mexico’s domestic market. In 2010, the company entered into a joint venture with giant Dutch brewers Heineken to become the leading global brewing concern.

In 1943, one of Femsa’s executives co-founded the Tec. de Monterrey (ITESM), a prestigious university that started in Monterrey and now has 31 campuses in 25 cities across the country.

We will continue our look at the geography of Mexico’s beer industry in a later post.

Mexico’s economic geography is analyzed in chapters 14–20 of Geo-Mexico: the geography and dynamics of modern Mexico. Buy your copy of this invaluable reference guide today!