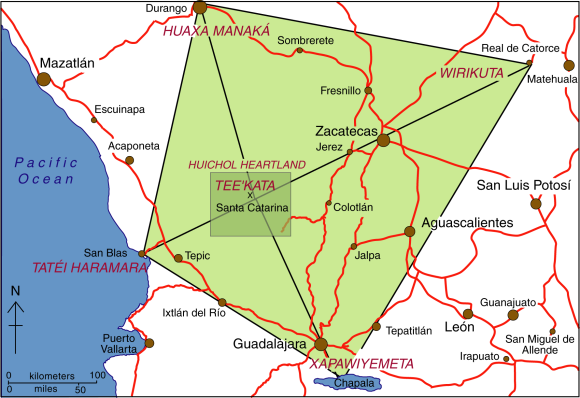

The remote mountains and plateaus of the north-west corner of Jalisco where it shares borders with the states of Nayarit, Durango and Zacatecas (see map) is home to some 18,000 Huichol Indians, as well as their close cousins, the Cora.

The Huichol heartland (central part of the rectangle on map) is an area of about 4100 square kilometers which straddles the main ridges of the Western Sierra Madre, with elevations of between 1000 and 3000 meters above sea level. There are dozens of dispersed small Huichol rural settlements (ranchos) in the area. We will take a detailed look at their settlements and traditional way of life in a future post.

In this post we focus on the regional setting of the Huichol heartland and the links that now exist between the Huichol and other places in the same general region of Mexico.

The Huichol refer to all other Mexicans (whatever their ethnic origin) as “mestizo”. The nearest non-Huichol “mestizo” towns are Mezquitic, Colotlán, Bolaños, Chimaltitán and Villa Guerrero, all in Jalisco, and all about 2-3 days’ walk from most Huichol settlements.

Migration to the tobacco fields

Many Huichol have left their home villages, where economic prospects are limited, in search of employment elsewhere. This kind of migration is often temporary or seasonal. For example, some Huichol undertake seasonal agricultural work, from November to May, on the tobacco plantations of coastal Nayarit. This may guarantee some income but the living conditions are poor, the work is hazardous and pesticide poisoning is all too common. Most of these Huichol return home each summer to plant their corn, beans and squash.

The center of tobacco cultivation is Santiago Ixcuintla, a town which has a very interesting support center for Huichol Indian culture and crafts. Tobacco cultivation, no longer as important as it once was, required as many as 15,000 local plus 27,000 temporary workers. While the businesses involved all have guidelines about how chemical sprays (including including Lannate, Diquat, Paraquat and Parathion) should be applied, these have rarely been effectively enforced. Many of the Huichol live in shanty-like accommodation in the fields, with no ready access to potable water. Some studies have shown that pesticide containers are sometimes used to carry drinking water. There have also been many cases of organophosphate (fertilizer) intoxication from working and living in the tobacco fields.

The tobacco workers often have no place to purchase basic food supplies apart from a store run by the same company they work for. The company holds their wages until the end of the week, and deducts the cost of any items they have bought. This is a virtually identical system to the “tienda de raya” system that was employed by colonial hacienda owners to economically enslave their workers.

Making the pesticide problems for the Huichol even worse is the fact that chemicals including DDT have been used to fumigate parts of Sierra Huichol in order to kill malarial mosquitoes. The Huichol refer to the DDT sprayers as “matagatos” (cat killers). The effects of most of these chemicals are cumulative over time.

Movement to the cities

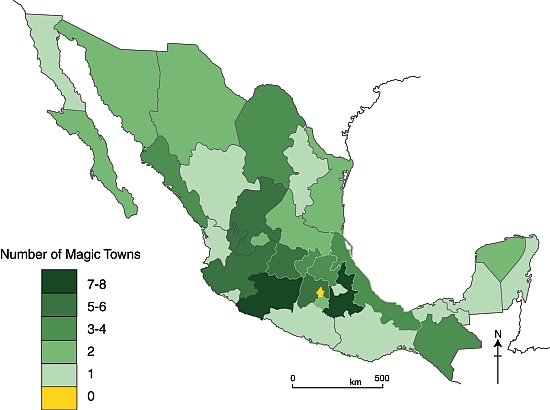

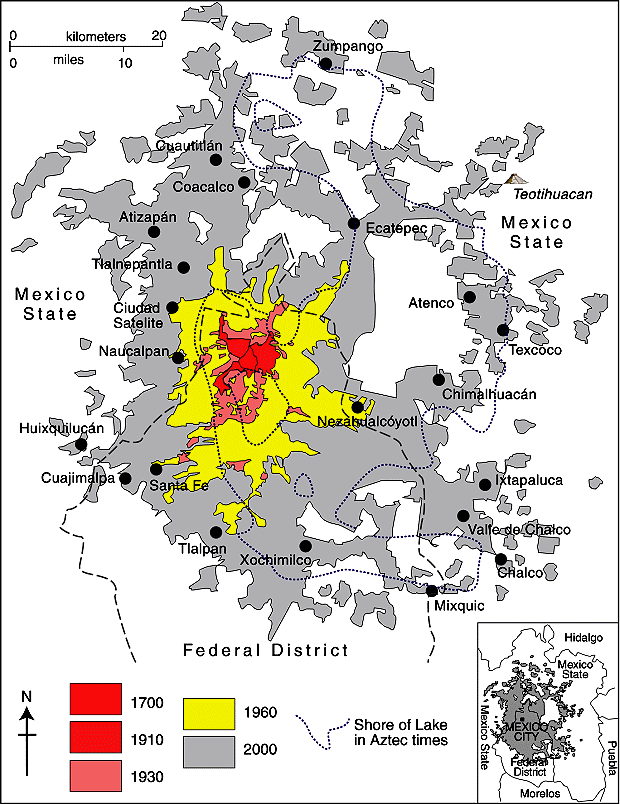

In the past thirty years, about four thousand Huichols have migrated to cities, primarily Tepic (Nayarit), Guadalajara (Jalisco) and Mexico City. It has also become quite common to see Huichol Indians (usually the menfolk in their distinctive embroidered clothing) in tourist-oriented towns, such as San Blas and Puerto Vallarta. To a large extent, it is these city-wise Huichols who, in search of funds, have drawn attention to their rich culture through their artwork and handicrafts. In addition to embroidered bags and belts, the Huichol make vibrant-colored bead work, yarn crosses and (more recently) yarn paintings, often depicting ancient legends. Income from artwork is very variable, but it is an activity that can include the participation of women. However, trading may depend on middle men who siphon off potential profits, and the Huichol artists now face stiff competition from non-Huichol imitators.

Encroachment by outsiders

As we saw in an earlier post—The sacred geography of Mexico’s Huichol Indians—the Huichol consider themselves the guardians of a large part of western Mexico. Inevitably, traditional Huichol lands have been encroached upon by outsiders for agriculture and ranching. Some non-Huichol ejidos have been established on land that was formerly communal Huichol land. Unfortunatley, the Huichol have had little defence against these pressures.

Mining interests are also threatening some traditional Huichol areas. For example, there is a serious dispute between the Huichol and the First Magestic Silver company over the area the Huichol call Wirikuta (where they gather their sacred peyote on an annual 800-km round-trip pilgrimage). First Majestic Silver has obtained permission from the Mexican government for its proposed La Luz Silver Project, which will extract silver from the Sierra de Catorce, despite this area’s historic significance for the Huichol.

Want to see their artwork?

One of the museums in the city of Zacatecas houses one of the relatively few museum quality displays of Huichol Indian art anywhere in Mexico. The collection was bought by the Zacatecas state government, in order to prevent its sale to the University of Colorado. The 185 embroideries (as well as many other items) were collected by Dr. Mertens, an American doctor who lived in Bolaños and worked for the Bolaños mining company. After the company closed its mines, Mertens continued to live in Bolaños, and to offer medical services to the Huichol, asking only for the occasional embroidery in lieu of payment. Another place to see high quality Huichol art is the small museum in the Basilica de Zapopan in the Guadalajara Metropolitan Area.

Related posts: