During the Irish potato famine more than one million people died of starvation when their staple crop failed, and many of those who survived were forced to emigrate. This tide of emigration carried many Irish people to North America, particularly to the north-east of the USA.

How did the potato famine come about? The census of 1841 in Ireland recorded a population of about 8 million. This figure was a staggering 300% more than sixty years earlier. The staple Irish food at that time was the humble potato and Ireland’s rapid population growth during the early part of the nineteenth century was based on the so-called “potato economy”. Ireland was bursting at the seams in 1841, but just a decade later, after the potato famine, the population had fallen to 6.5 million and by 1900 to around 4 million.

And where does a Mexican mold come in? The cause of famine was a water mold (Phytophthora infestans) that originated in Mexico. This fungus-like mold results in a disease called “late blight” in which entire fields of mature potato plants are destroyed within days. The name “late blight” is because the mold strikes late in the growing season, close to harvest time. Infected tubers are subject to soft-rot bacteria which render them useless as food. What is worse, the discarded rotting tubers can easily re-infect the succeeding year’s crop.

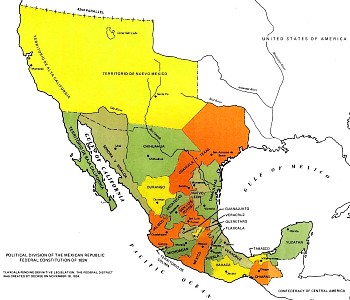

One kind of late blight mold, A1, crossed the Atlantic in the 1840s, reaching Europe in 1845 before rapidly spreading across the continent to reach Ireland. Although cultivated potatoes (Solanum tuberosum) originated in Peru, the late blight mold appears to have originated in the Toluca Valley of Mexico (adjacent to the western edge of Mexico City) where it is found in several related wild-growing Solanum tubers.

One kind of late blight mold, A1, crossed the Atlantic in the 1840s, reaching Europe in 1845 before rapidly spreading across the continent to reach Ireland. Although cultivated potatoes (Solanum tuberosum) originated in Peru, the late blight mold appears to have originated in the Toluca Valley of Mexico (adjacent to the western edge of Mexico City) where it is found in several related wild-growing Solanum tubers.

After the Irish potato famine, farmers learned to control the A1 mold through careful fungicide applications and by choosing varieties that had some resistance to late blight and planting only healthy tubers.

Since the 1980s, however, farmers are once again fighting late blight as the direct result of the escape of a second kind, A2, into the cultivated potato population. The problem stems from the fact that A1 and A2 can reproduce sexually, with the potential to have offspring that are strains with greater virulence or increased resistance to fungicides. Having two different kinds of late blight as parents greatly magnifies the genetic variability available for future generations of the mold .

The A2 mold first appeared outside Mexico in the 1970s and has already spread with serious economic consequences to the Middle East, Africa and North and South America. It seems almost certain that it will eventually also disrupt harvests in India and in China, the world’s largest potato producer. The A2 mold is considered the most important threat to potato cultivation worldwide. The current response of hitting it with higher and more lethal doses of fungicide is not in line with public demands for greener farming methods.

How did the A2 mold escape from Mexico? It was probably unintentionally carried by potatoes exported to Europe during the winter of 1976-77. Europe needed potatoes because a drought a year earlier had reduced its potato yields significantly. Unrecognized, the mold was then re-transported in seed potatoes throughout Europe and to the Middle East and Africa.

Scientists are studying wild potatoes in the Toluca Valley in an effort to try and identify precisely which gene or combination of genes provides these particular wild potatoes with some degree of defense against the worst ravages of the mold. Mexico’s main center for potato research is the Agricultural University at Chapingo, near Texcoco, on the eastern edge of Mexico City. The University is well worth a visit – if only to admire the magnificent Diego Rivera murals, including one of the world’s great nudes.

Happy St. Patrick’s Day, wherever you may be!

This is an edited version of an article originally published on MexConnect – Click here for the original article

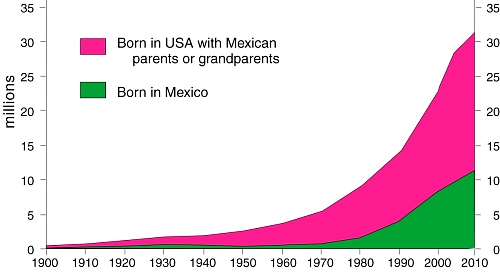

Mexico’s innumerable links (economic, social, demographic and cultural) to the world are relevant to many chapters of Geo-Mexico: the geography and dynamics of modern Mexico.