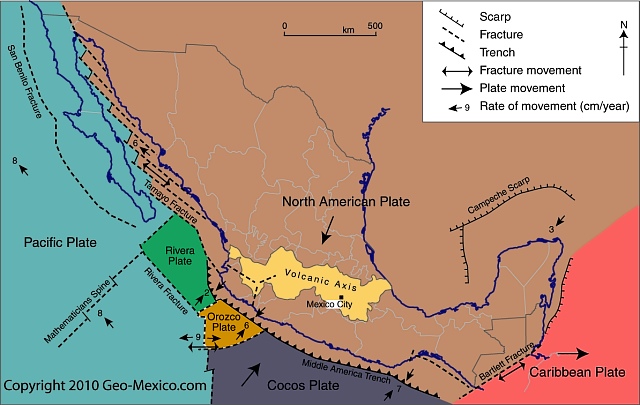

In a previous post, we identified the tectonic plates that affect Mexico. In this piece, we look at some of the major impacts of Mexico lying on or close to so many different plates.

To the east of Mexico, in the last 100 million years, outward expansion from the Mid-Atlantic Ridge (a divergent boundary) first pushed South America ever further apart from Africa, and then (slightly more recently) forced the North American plate (and Mexico) away from Eurasia. The Atlantic Ocean continues to widen, expanding the separation between the New World and the Old World, by about 2.5 cm (1 in) each year.

Meanwhile, to the west of Mexico, an analogous situation is occurring in the Pacific Ocean, where the Cocos plate is being forced eastwards away from the massive Pacific plate, again as a result of mid-ocean activity. The Cocos plate is effectively caught in a gigantic vice, its western edge being forced ever further eastwards while its leading eastern edge smacks into the North American plate.

The junction between the Cocos and North American plates is a classic example of a convergent plate boundary. The collision zone is marked by a deep ocean trench, variously known as the Middle America trench or the Acapulco trench. Off the coast of Chiapas, this trench is a staggering 6662 m (21,857 ft) deep. The trench is formed where the Cocos plate is forced to dive beneath the North American plate.

As the Cocos plate is subducted, its leading edge fractures, breaks and is partly re-melted into the surrounding mantle. Any cracks in the overlying North American plate are exploited by the molten magma, which is under immense pressure, and as the magma is forced to the surface, volcanoes form. The movement of the plates also gives rise to earthquakes. The depth of these earthquakes will vary with distance from the deep ocean trench. Those close to the trench will be relatively shallow, whereas those occurring further away from the trench (where the subducting plate is deeper) will have deeper points of origin.

As the plates move together, sediments, washed by erosion from the continent, collect in the continental shallows before being crushed upwards into fold mountains as the plates continue to come together. A line of fold mountains stretches almost continuously along the west coast of the Americas from the Rocky Mountains in Canada past the Western and Southern Sierra Madres in Mexico to the Andes in South America. Almost all Mexico’s major mountain ranges—including the Western Sierra Madre, the Eastern Sierra Madre and the Southern Sierra Madre—formed as a result of these processes during the Mesozoic Era, from 245 to 65 million years ago.

However, no sooner had they formed than another momentous event shook Mexico. About 65 million years ago, a giant iridium-rich asteroid slammed into the Gulf of Mexico, close to the Yucatán Peninsula, causing the Chicxulub Crater, and probably hastening the demise of the dinosaurs. An estimated 200,000 cubic km of crust was pulverized; most of it was thrown into the air. The resulting dust cloud is thought to have contributed to the extinction of up to 50% of all the species then on Earth. Not only did this event have an enormous impact on all life forms on Earth, it also left a legacy in the Yucatán. The impact crater is about 200 km (125 mi) across. Its outer edge is marked by a ring of sinkholes (locally known as cenotes) and springs where the fractured crust provided easy access to ground water. These locations include the ria (drowned river valley) of Celestún (now a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve), where fresh water springs mingle with salt water to create an especially rich habitat for birdlife.

In the 65 million years since the asteroid impact (the Cenozoic period), the remainder of Mexico has been formed, including many of the plateaus and plains, and the noteworthy Volcanic Axis, which owes its origin to still-on-going tectonic activity at the junction of the North American and Cocos plates.

Related posts:

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.