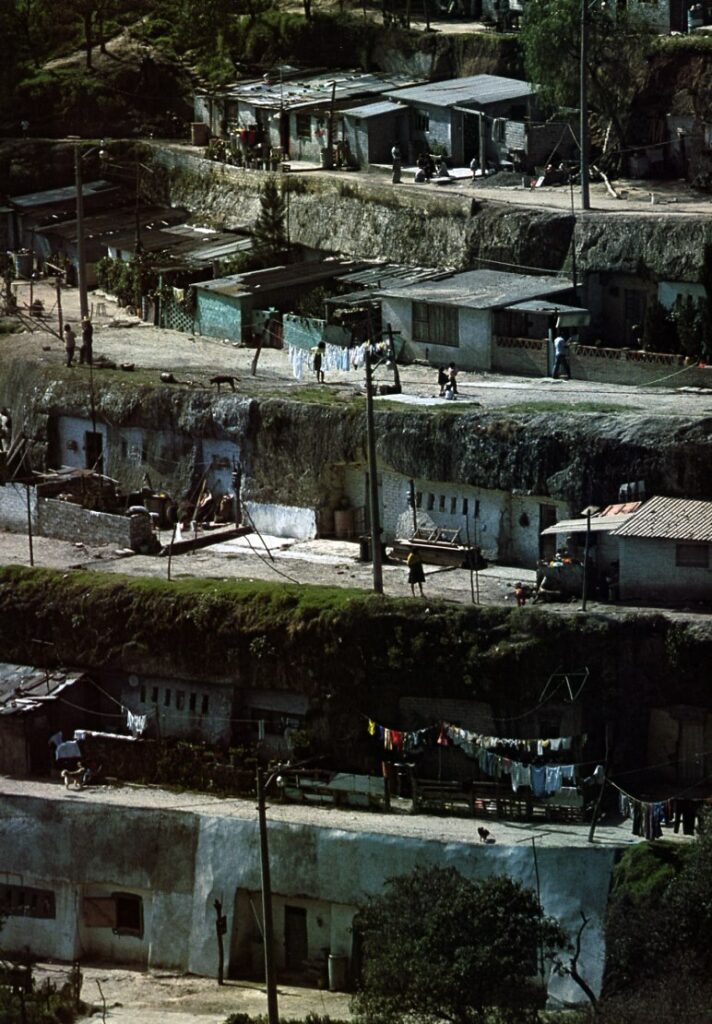

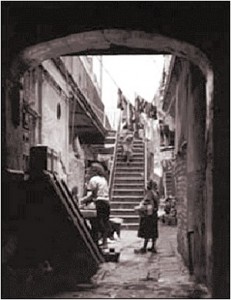

Rapid industrialization north of Mexico City after World War II brought a giant wave of immigrants aggravating a serious shortage of low income housing. With the vecindades (inner city slums) severely overcrowded, the only alternative was “irregular housing” or “colonias populares.” These were developed wherever there was vacant land, mostly in the west and north of the city on the dry former lakebed or on very steep slopes. They all followed a development pattern roughly similar to that of Nezahualcoyotl, the largest and best known colonia popular.

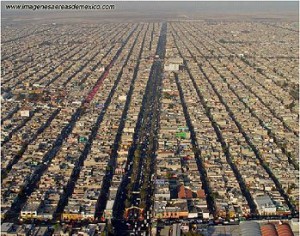

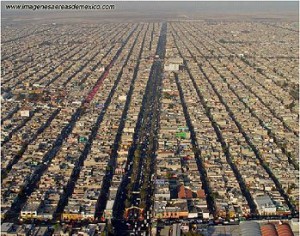

The densely packed housing of Nezahaulcoyotl in all its glory. Image: imagenesaereasdemexico.com. Follow link at end of post for more Mexico City photos

In the late 1950s, a group of speculators gained de facto possession of roughly 78 square kilometers (30 square miles) of former lakebed in Nezahualcoyotl just east of the Mexico City airport. They sold nearly 200,000 plots cheaply and on credit, a few dollars down, and a few dollars a month, for 10-20 yrs.

Families bought plots and immediately started to erect shacks. Aside from electricity, which was provided by the national utility, the plots initially lacked basic services such as potable water, sewerage, flood drainage, pavement, schools, etc. Without services, Nezahualcoyotl was illegal under State of Mexico law; but the government tolerated this situation.

The community became an immediate boom town. By 1970, the population was over 600,000, but still over half the area was without paved streets, water supply and drainage. Summer brought floods while the rest of the year it was an arid dust bowl.

Residents became frustrated with the broken promises of the developers, demanded that they be jailed for fraud, and stopped their monthly payments. The feud lasted for years and some developers were actually jailed. Eventually most of the area was “regularized”, meaning that residents got legal deeds and basic services. They continued to improve their houses and communities.

Nezahualcoyotl, the city of dreams

By 1980, the population reached about 1.3 million, making it one of the largest and most densely populated municipalities in the country.

By 2000, Nezahualcoyotl had essentially joined the mainstream. Nearly all residents had electricity and TVs, over 80% had refrigerators, 60% had telephones, nearly one in three had access to an automobile, and almost one in five had a computer. While Nezahualcoyotl has slums, gangs and crime, it also has tree-lined boulevards, parks, a zoo, banks, shopping centers, offices, libraries, hospitals, universities, cinemas, and apartment buildings. It even has a cathedral (since 2000) and an Olympic sports stadium, which hosted some 1986 FIFA World Cup matches. Currently, it is a vital part of metropolitan Mexico City and provides jobs for almost 250,000.

From irregular settlement to massive urban monster; Cd. Nezahualcoyotl has certainly come a long way!

Mexico’s cities and towns are analyzed in chapters 21, 22 and 23 of Geo-Mexico: the geography and dynamics of modern Mexico. Buy your copy today!!