Six months ago, we gave an optimistic mention of Maya Biosana, a cacao megaproject in Quintana Roo, noting that it had received the support of the federal Agriculture Secretariat (Sagarpa):

We also noted that the project was not without its critics. In this post, we look at some of the claims, counterclaims and available evidence.

What is Maya Biosana?

The Maya Biosana project aims to make Mexico the leading producer of organic cacao in the Americas. In the early phases, Maya Biosana claims it will plant one million cacao trees to create 500 hectares (1200 acres) of irrigated orchards in 12 communities near Chetumal in Quintana Roo, with similar numbers of new trees to be planted annually for another three years. The trees are expected to yield 2.4 metric tons of cacao per hectare, produce 4800 metric tons of cacao a year (destined for high quality chocolates) by 2017 and provide up to 2,000 additional jobs.

A fuller description of the intended project (pdf file, in Spanish) is available on the Sagarpa website.

Pipedream or reality?

Industry insiders, such as Denver-based chocolate maker Steve DeVries, who leads specialist tours to the cacao growing regions of Mexico, Costa Rica and Ecuador, have drawn our attention to the fact that such numbers will be virtually impossible to achieve. In their view, producing and planting one million cacao plants will take far longer than a year, even in ideal circumstances. They also point out that a million trees on 500 hectares would be an average planting density of 2000 plants/hectare. According to the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), about half that figure, 1025 plants/hectare, would be a more normal spacing.

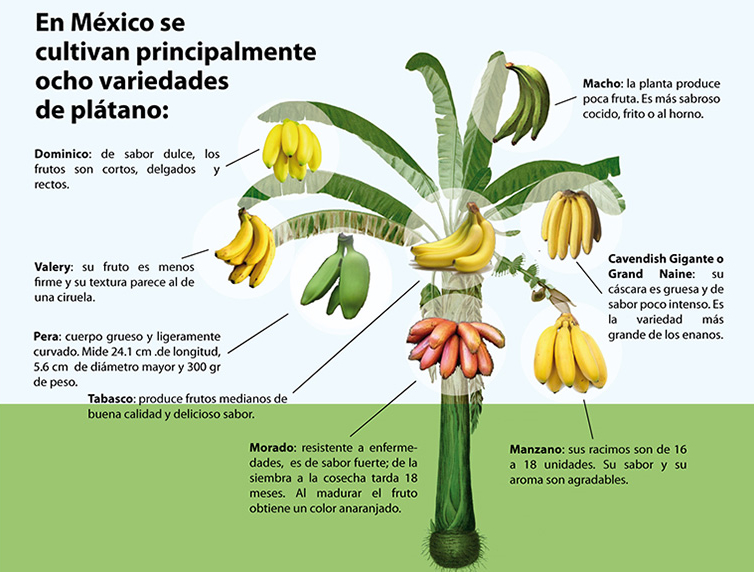

The Maya Biosana project apparently intends to plant only cacao Criollo. Of the three main varieties of cacao (see further reading for more details) – Forastero, Criollo and Trinitario – Criollo produces the most flavorful chocolate, but is little used at present in the mainstream chocolate industry because it is very susceptible to disease, and takes longer to reach maturity. The most widely grown variety is Forastero, which is hardy but least flavorful, while Trinitario, a hybrid of the first two, falls somewhere in the middle.

This makes Criollo a very strange choice for such a major plantation. In fact, industry insiders say, there is no source anywhere in Mexico for the huge quantity of Criollo grafts that the Maya Biosana project would require.

Maya Biosana claims that the first phase of its megaproject is already underway on land in the Los Divorciados ejido, about 100 km from Chetumal, and recently released a promotional video. The film includes lots of “feel good” footage and memorable quotes, but some of the footage of mature cacao appears to have been shot elsewhere, presumably in Tabasco state. More importantly, what exactly does the Maya Biosana team bring to the table, besides good intentions?

Who are the main players in Maya Biosana?

The two main players in Maya BioSana, according to press reports, are Jim Walsh and Fernando Manzanilla.

Entrepreneur Jim Walsh is the self-styled “reinventor of chocolate”, CEO of Hawaiian Vintage Chocolate from 1992, and CEO of the closely-related Intentional Chocolate since 2007. Fernando Manzanilla Prieto is a well-connected Mexican politician, member of Partido Acción Nacional (PAN), and businessman who is currently the Secretary General of the government of the state of Puebla in central Mexico.

According to its website, samples of Intentional Chocolate, co-founded by Walsh and Manzanilla, were given by former president Bill Clinton as a gift to the Japanese Royal family and have the seal of approval of the Dalai Lama. The company “treats” regular chocolate using “breakthrough licensed technology” that “helps embed the focused good intentions of experienced meditators and then infuses those intentions into chocolate”. An early press release stated that such chocolate can “significantly decrease stress, increase calmness, and lessen fatigue in those who consume it”.

The major claim made for this chocolate is that it elevates the mood of consumers more than non-intentioned chocolate does. This claim is based, apparently in its entirety, on a single “double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled experiment”, the results of which were published in an article, co-authored by Walsh, entitled Effects of Intentionally Enhanced Chocolate on Mood in EXPLORE: The Journal of Science & Healing, an Elsevier journal, in the September/October issue of 2007 (Vol 3, No 5: 485-492).

The sample size was small, 62 individuals in total. For one week, participants self-recorded their mood by means of a recognized “profile of mood states”. Some participants consumed “intentioned” chocolate, and others “non-intentioned” chocolate, twice a day, at the same times, for three consecutive days, in the middle of the week.

The most fascinating part of the article is actually the last paragraph, where the authors recommend that efforts to replicate the findings should “seriously consider sources of intentional enhancement and contamination that might influence the postulated effect.” They call for intentional imprints to be provided only by “highly experienced meditators or other practitioners”, writing that “persons holding explicitly negative expectations should not be allowed to participate for the same reason that dirty test tubes are not allowed in biology experiments.” Even more bizarrely, they claim that vigilance about the intentions of people involved in the test may even extend to “people who learn about the experiment in the future after the study is completed”.

Put another way, skeptics and disbelievers should stay home.

To the best of our knowledge, the Explore study has not been replicated, while statisticians and others have criticized the methods used and the conclusions drawn. See, for example, Debunked: Effects of Intentionally Enhanced Chocolate on Mood.

The other two authors of the Explore study besides Walsh are Dean Radin and Gail Hayssen. Radin is a prolific author of articles about parapsychology and also just happens to be a co-editor of Explore. Both Radin and Hayssen hold posts at the Institute of Noetic Sciences in Petaluma, California.

Walsh and Radin, together with Manzanilla, all have connections to the Human Energy Systems Alliance (HESA) Institute, “an alliance of scientists, philosophers, entrepreneurs, and spiritual leaders devoted to unlocking the potential of the human energy system and to developing technologies and products that transform human health and increase human flourishing.”

According to the HESA Institute’s list of its main members (webpage no longer active) , Walsh is the institute’s founder and CEO, and Radin is a prominent member. Manzanilla’s bio claims that he was, too, founded HESA but, curiously, his name is absent from the HESA Institute list.

Between them, Walsh and Manzanilla have created an impressive web of interlinked and overlapping projects, supported by an equally dazzling range of positions on advisory boards. For example, both men are members of the three-person advisory board of the Institute for Spirituality and Wellness (ISW) at the Chicago Theological Seminary (CTS), which continues “to educate and prepare future leaders for a multitude of ministries” (Ref). The CTS is an affiliated seminary of the United Church of Christ, “a mainline Protestant Christian denomination primarily in the Reformed tradition but also historically influenced by Lutheranism” (Ref).

Several of the projects associated with Manzanilla, according to his CTS bio, have surprisingly little or no web presence. For example, he founded (in 2007 according to his Linkedin profile) and remains CEO of ImaginaMéxico, which “directs a network of organizations whose brands encompass the areas of food and beverages, agro forestry and wellness, human capital and technology, all under the common theme of helping individuals lead more meaningful and vital lives.” Yet, as of last week, the ImaginaMéxico website was “under construction”. According to the bio, Manzanilla also founded Cielo y Tierra (no web links found), Facthum-Mexico (no website found) and Kakaw Universal (no evidence from a Google search that it even exists)…. Manzanilla also co-founded Baja BioSana, “an intentional community with a vision to become an example of sustainable living and educational center” (Ref) located in the small village of El Choro in Baja Califórnia Sur.

Financial shenanigans

It now looks as if the Maya Biosana project may be dead in the water, before it ever really gets off the ground. According to this document from the Superior Audit Office of Mexico (Auditoría Superior de la Federación), Maya BioSana received two payments in 2010 from Financiera Rural, acting on behalf of Sagarpa, as part of the latter’s Strategic Project for Sustainable Rural Development in the South-South-East Region of Mexico (Proyecto Estratégico para el Desarrollo Rural Sustentable de la Región Sur Sureste de México). The two payments totaled 15 million pesos (about $1,140,000 dollars). The document states that Sagarpa is already requesting the return of these funds because the Maya Biosana project has fallen behind schedule.

The Superior Audit Office document says that visits to the site did not find any cacao plantation and alleges that the Sagarpa funds had been transferred from one company account to another before a payment for 12,400 million pesos (about $946,000 dollars) was made to a foreign bank account belonging to one of the individuals who had signed on behalf of the company “Maya Biosana S.A.P.I de C.V.” Perhaps this was the cost of the recently-released video?

For the sake of the ejidatorios of Los Divorciados in Quintana Roo, who were counting on the success of the Maya BioSana cacao-growing megaproject, we hope that they have gained, and will gain, more from this experience than they lost. They deserve far better than a mere handful of chocolate-coated intentions.

This is one chocolate megaproject that appears to be melting fast. Maya BioSana looks much more like Maya Bio-Insana.

Further reading:

- Cacao domestication I: the origin of the cacao cultivated by the Mayas

- Cacao domestication II: progenitor germplasm of the Trinitario cacao cultivar

Related posts: