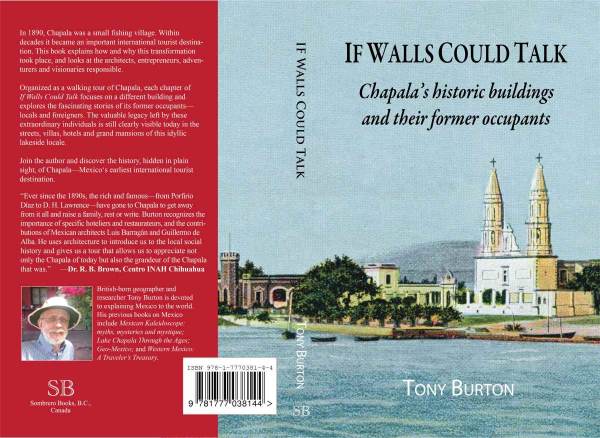

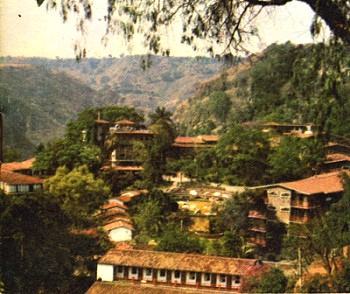

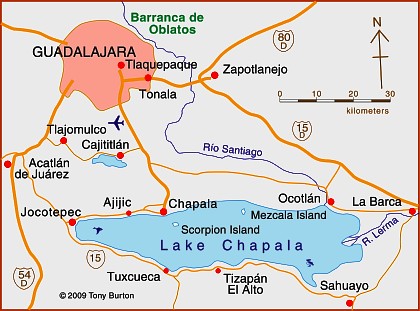

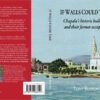

The town of Chapala, on the shores of Lake Chapala—Mexico’s largest natural lake—played an important role in the history of tourism in North America and has become one of the world’s premier retirement destinations. Yet, the details of how and why this transformation occurred have never been adequately reconstructed… until now!

My latest book If Walls Could Talk: Chapala’s historic buildings and their former occupants, reveals the results of more than two decades of research. The book explores the history of the town’s formative years and shares the remarkable and revealing stories of its many historic buildings and their former residents.

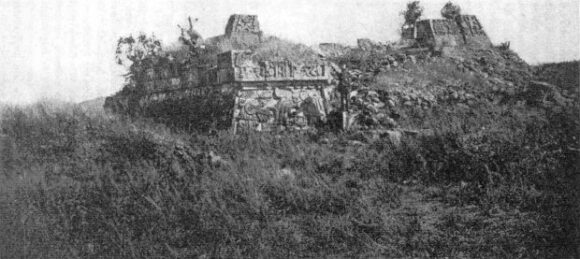

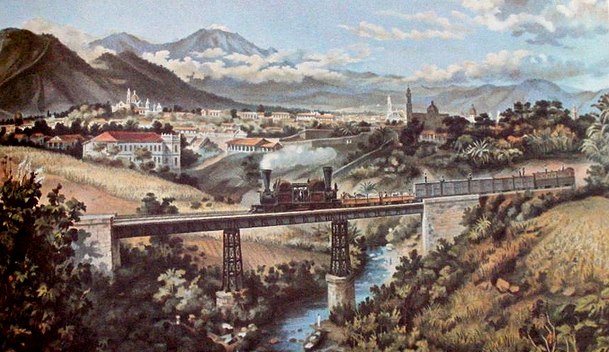

The front cover shows the waterfront of Chapala at the start of the twentieth century. On the right is the parish church of San Francisco, which dates back to the sixteenth century and features in D. H. Lawrence‘s novel The Plumed Serpent, set at the lake. (The house Lawrence rented in 1923 is now a boutique bed and breakfast.) The turreted tower on the left is part of the Villa Ana Victoria which was built by the Collignon family of Guadalajara in the 1890s, right at the start of the village’s explosive growth.

The illustration is a photograph by American photographer Winfield Scott that was colorized and published in about 1905 by Jakob Granat, a postcard publisher based in Mexico City.

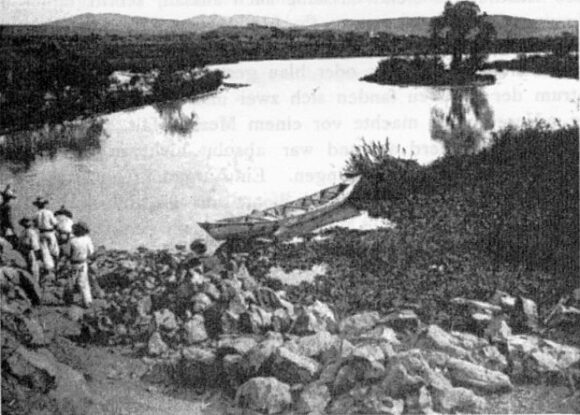

In 1890, Chapala was a small fishing village. Within decades it became an important international tourist destination. This book explains how and why this transformation took place, and looks at the architects, entrepreneurs, adventurers and visionaries responsible. The cast of characters includes Mexican and British politicians and diplomats, as well as the eccentric Englishman Septimus Crowe, who abandoned his wife and child in Norway and carved out a new life for himself by investing in Mexican mines and importing a German-built yacht to sail the lake. Crowe was the area’s first real estate developer and pressured friends and acquaintances to join him in Chapala. One of the town’s central streets is named after him.

Chapala’s transformation into an international tourist destination was aided by its links to dictatorial President Porfirio Díaz, whose wife’s relatives lived on the outskirts of the town, and by a host of business leaders and wealthy, high society families from Mexico City and Guadalajara.

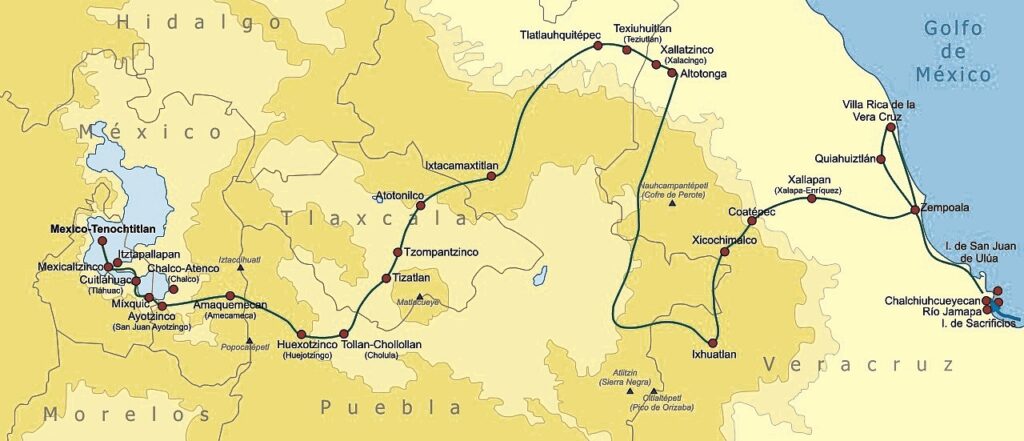

The story of Chapala is truly international. The visionary Norwegian entrepreneur Christian Schjetnan refused to take no for an answer as he worked tirelessly to organize a Chapala Development Company, start a yacht club, run steamboats on the lake, and build a branch railroad linking Chapala to the Central Mexican Railroad mainline at La Capilla, near Atequiza.

Chapala’s first major hotel, the Hotel Arzapalo which opened in 1898, was built by a Mexican businessmen and had a succession of Italian managers, some more honest than others. Many members of the extensive French and German communities in Guadalajara also played key roles in the area, both by building private family villas in Chapala and by helping finance improvements and public buildings in the town.

Organized as a walking tour of Chapala, each of the 42 chapters of If Walls Could Talk focuses on a different building and explores the fascinating stories of its former occupants—locals and foreigners. The valuable legacy left by these extraordinary individuals is still clearly visible today in the streets, villas, hotels and grand mansions of this idyllic lakeside locale.

- Print Version (US/Canada)

- Kindle E-book version

- Print Version (Mexico)

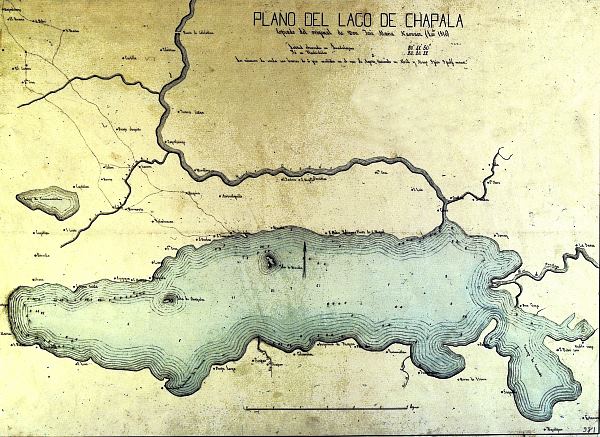

The book includes more than 40 vintage photographs and four original maps showing how Chapala’s street plan has changed over the years. The text is supported by a bibliography, index and detailed reference notes.