In honor of the award of the 2019 Nobel Prize for Economics to Abhijit Banerjee, Esther Duflo and Michael Kremer for their experimental approach to alleviating global poverty, we republish this post from five years ago in which we highlighted the significance of the pioneering work of Banerjee and Duflo:

Every so often a book comes along that shakes up established wisdom and forces us to rethink our viewpoints and beliefs. The latest such book to cross my desk is Poor Economics: A Radical Rethinking of the Way to Fight Global Poverty by Abhijit V. Banerjee and Esther Duflo, published by PublicAffairs in 2011.

This is a worthy read for anyone interested in development theory, policy, practice and economics. The authors are professors of Economics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and co-founded the Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab (J-PAL). Their book reports on the effectiveness of solutions to global poverty using an evidence-based randomized control trial approach.

This is a worthy read for anyone interested in development theory, policy, practice and economics. The authors are professors of Economics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and co-founded the Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab (J-PAL). Their book reports on the effectiveness of solutions to global poverty using an evidence-based randomized control trial approach.

Banerjee and Duflo argue that many anti-poverty policies have failed over the years because of an inadequate understanding of poverty. They conclude that the battle against poverty can be won, but it will take patience, careful thinking and a willingness to learn from evidence.

The authors look at some of the unexpected questions related to poverty that empirical studies have thrown up, such as :

- Why do the poor (those living on less than 99 cents a day) need to borrow in order to save?

- Why do the poor miss out on free life-saving immunizations but pay for drugs that they do not need?

- Why do the poor start many businesses but do not grow any of them?

The book was supported by an outstanding website that included:

- Introductions to each chapter

- Maps showing cited studies with links to original sources

- Data and figures used with interactive data tools

- A “What Can You Do” page with links to major organizations working in the field or for the problem discussed in the chapter

The website’s links to research papers mentioned in the book included four studies related to Mexico:

1. Do Conditional Cash Transfers Affect Electoral Behavior? Evidence from a Randomized Experiment in Mexico, by Ana L. De La O.

The evidence comes from the pioneering Progresa, the original Mexican conditional cash transfer (CCT) program (since repackaged as Oportunidades). This CCT program led to a 7% increase in turnout and a 16% increase in the incumbent vote share, with clear implications for politicians in areas where CCT programs reach a large percentage of voters.

2 School Subsidies for the Poor: Evaluating the Mexican Progresa Poverty Program, by T. Paul Schultz of Yale University (August 2001).

This study considered how a CCT program affected school enrollment. The CCT program increased enrollment in school in grades 3 through 9, with the increase often greater for girls than boys. The cumulative effect was estimated to add 0.66 years to the baseline level of 6.80 years of schooling.

3 Experimental Evidence on Returns to Capital and Access to Finance in Mexico, by David McKenzie and Christopher Woodruff (March 2008)

Microenterprises are often unable to access suitable financing, even though they are responsible for employing a large portion of the total workforce. This experiment, which gave cash and in-kind grants to small retail firms, demonstrated that this additional capital generated large increases in profits, with the effects concentrated on those firms which were more financially constrained. The estimated return to capital was found to be at least 20 to 33 percent per month, three to five times higher than market interest rates.

4 Working for the Future: Female Factory Work and Child Health in Mexico, by David Atkin (April 2009)

Atkins’ paper found that children whose mothers lived in a town where a maquiladora (export factory) opened when the women were sixteen years old were much taller than those children born to mothers who did not have a similar opportunity. The effect was so large that “it can bridge the entire gap in height between a poor Mexican child and the “norm” for a well-fed American child.” (Poor Economics, 229)

The increase in height could not be fully explained by the changes in family income resulting from employment in a maquiladora. As Bannerjee and Duflo suggest, “Perhaps the sense of control over the future that people get from knowing that there will be an income coming in every month -and not just the income itself- is what allows these women to focus on building their own careers and those of their children. Perhaps this idea that there is a future is what makes the difference between the poor and the middle class.” (Poor Economics, 229)

Conclusion

Banerjee and Duflo’s positive message is that poverty can indeed be alleviated, but we need to take one small measurable step at a time with constant evaluation of whether or not particular policies are successful, based on evidence, not just on belief systems.

“Poor Economics: A Radical Rethinking of the Way to Fight Global Poverty” deserves its place of honor alongside other such genuine classics as E.F. Schumaker’s “Small Is Beautiful: A Study of Economics As If People Mattered” (1973). It is a must-read for geographers, regardless of your political persuasion.

Note: this is a lightly edited version of a post first published 27 January 2014.

Related posts

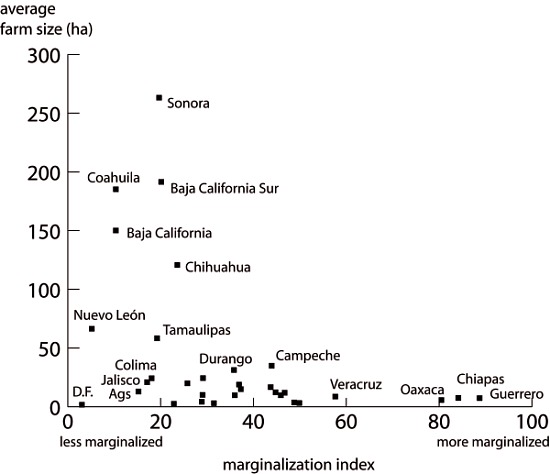

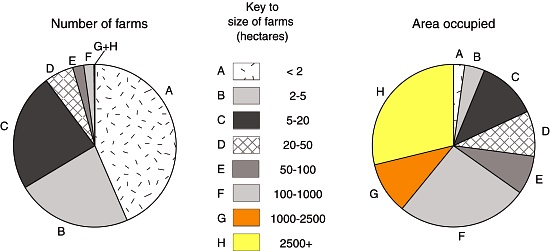

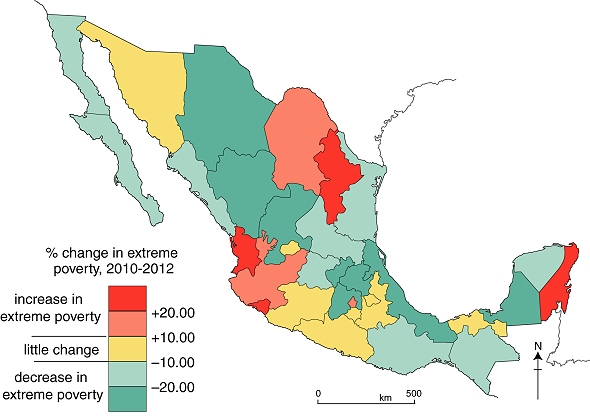

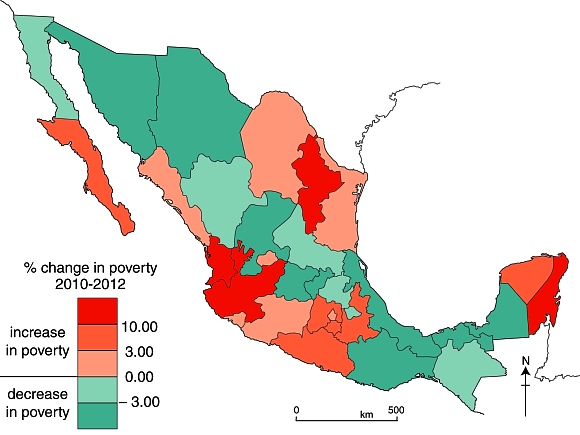

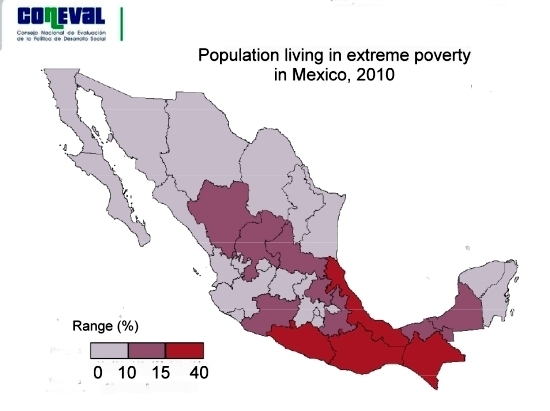

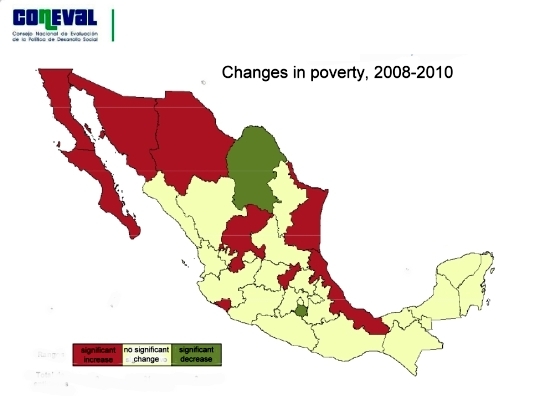

- Poverty on the rise in some states in Mexico (Jan 2014)

- The world’s richest man is one of 15 Mexican billionaires on 2013 Forbes list (Mar 2013)

- The widening income gap in Mexico; the rich earn 26 times more than the poor (Dec 2011)

- The GINI index: is inequality in Mexico increasing? (Oct 2011)

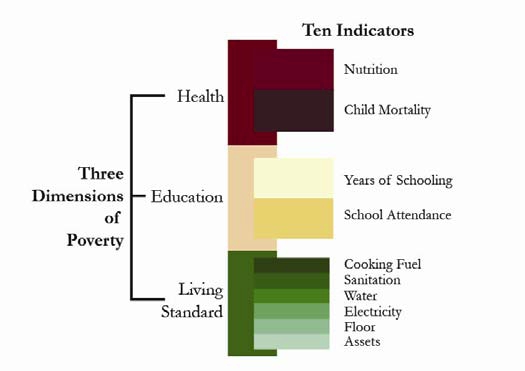

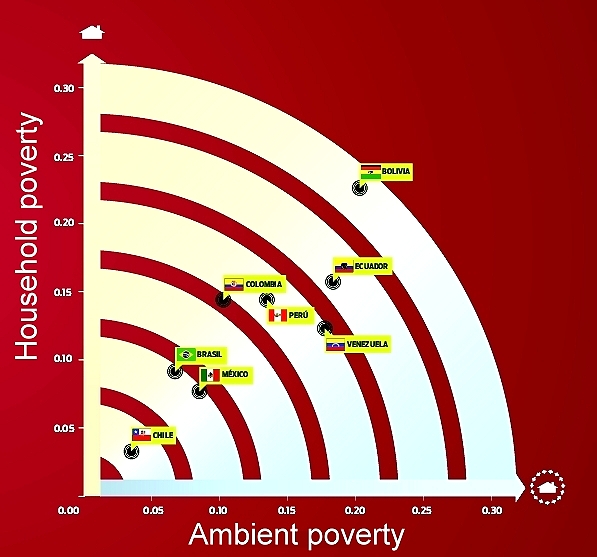

- The measurement of poverty: the Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI) (Sep 2011)

- J.K. Galbraith talks about Mexico’s poverty and inequality (Aug 2012)

- The Ethos Foundation’s Multidimensional Poverty Index (Sep 2011)

- Oportunidades – Mexico’s flagship social development program (Jan 2010)