In a previous post — The re-opening of the giant El Boleo copper mine in Santa Rosalía, Baja California Sur — we looked at the repeated boom-bust-boom history of the copper mining center of Santa Rosalía on the Baja California Peninsula. The arid peninsula did not offer much in the way of local resources for the construction of a mining settlement. When mining took off, an entire town was needed, virtually overnight. Almost all the materials necessary for the construction and exploitation of the mines and for building the houses and public buildings had to be imported, primarily from the USA.

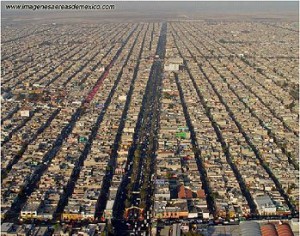

As the town grew at the end of the nineteenth century, a clear geographic (spatial) segregation developed, which is still noticeable even today:

- Workers’ homes were built on the lowland near the foundry and port

- Higher up the slope was the Mexican quarter where government workers and ancillary support staff lived

- The highest section of town, overlooking everything, was the French quarter.

The contrasts of Santa Rosalía at this time were well summed by María Eugenia B. de Novelo:

“Santa Rosalía was a place of clashing contrasts and situations. It had a scarred backdrop of copper hills, a black-tinted shore, French silks, fine perfumes, crystal, Bordeaux wines and Duret cooking oil, sharing the scene with flour tortillas, giant lobsters, abalone and chimney dust.”

The French quarter has retained its distinctive architecture to the present day. At one end is the Hotel Francés, opened in 1886, which has an incredibly stylish period interior and still operates today.

The gorgeous architecture of many of the homes of the French quarter is reminiscent of New Orleans. Beautiful wooden houses stand aloof on blocks with porches, balconies and verandas, competing for the best view over the town below. Wooden homes are decidedly unusual in this part of Mexico, which was never forested, and are, indeed, rare almost everywhere in the country. There are so many wooden homes here that Santa Rosalía has long had its own fire department, just in case!

At the other end of the French quarter are the former mining offices, now the Museo Boléo, an interesting museum where interior details are little changed from a century ago. Standing in the main hall, it is possible to imagine the hustle and bustle of former days, as clerks work feverishly to keep up with their superiors’ numerous demands. The mining company attracted workers from far afield. Three thousand Chinese workers arrived, settling the districts still known as La Chinita and Nuevo Pekin.

The most conspicuous landmark in the main part of town remains the former foundry, no longer open to the public. The next most conspicuous landmark is the church of Santa Bárbara. There are serious doubts as to who designed this unusual church, assembled out of pre-fabricated, stamped steel sheets or plates. Most guidebooks attribute the church to Gustave Eiffel, the famous French architect responsible for the Eiffel Town in Paris. According to this version, Eiffel’s design won a prize at the 1889 Universal Exposition of Paris, France, and was originally destined for somewhere in Africa. It was later discovered in Belgium by an official of the Boleo mining company, who purchased it and brought it back to Santa Rosalía in 1897.

The latter part of the story may be correct, but research by Angela Gardner (see Fagrell, 1995) strongly suggests that the original designer was probably not Eiffel but is far more likely to have been a Brazilian, Bibiano Duclos, who graduated from the same academy as Eiffel in Paris. Duclos took out a patent on pre-fabricated buildings, whereas there is no evidence that Eiffel ever designed a pre-fabricated building of any kind. Whoever designed it, it is certainly a unique design in the context of Mexico, and well worth seeing.

Other well-preserved buildings dating back to the heyday of the town’s success include the municipal palace or town hall (formerly a school designed by Gustave Eiffel), the Central Hotel, the DIF building, the Club Mutualista, the Post Office and the Mahatma Gandhi library, currently being restored. The library is in Parque Morelos, which is also the last resting place for a Baldwin locomotive dating back to 1886.

If walking around town looking at the architecture makes you hungry, try the French pastries (and Mexican sweet breads) from the Panadería El Boleo on the main street. With slight hyperbole, Panadería El Boleo boasts on its wall of being the World’s most famous bakery. Expect to queue, but enjoy the smells of fresh baked goods while you wait.

The distinctive history, architecture (and pastries) of Santa Rosalía, assuming they are conserved, should prove in the future to be an excellent basis for the development of cultural tourism to supplement the ecotourism and adventure tourism already in place.

Sources:

- de Novelo, María Eugenia B. A History of Santa Rosalía in Baja California. The Journal of San Diego History: Winter 1989, vol 35 #1. Includes a link to some wonderful old photos.

- Fagrell, Truls M. Mystery of Santa Rosalia’s Church. The Mexico City News. July 15, 1995.

- Luft, Wendy A. Where Eiffel Towers Over Mexico. Travel Mexico, May-June 1994.

- North of Loreto: Mulege and Santa Rosalía, sun, beaches, hotels and history (Original article on MexConnect).

Want to read more?

- How sustainable is organic agriculture on the Baja California Peninsula in Mexico?

- Desalination plants for the Baja California Peninsula

- Why is the world’s largest salt-works in Baja California Sur?

- The re-opening of the giant El Boleo copper mine in Santa Rosalía, Baja California Sur

Note : This post was first published 11 October 2011.