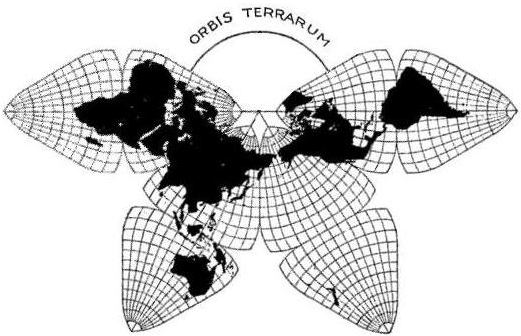

One of the more beautiful, unusual and useful map projections ever devised was created by cartographer Bernard Cahill. The butterfly projection was first published in the Scottish Geographical Magazine in 1909. Cahill (1866-1944) later applied for a US patent to protect his creation.

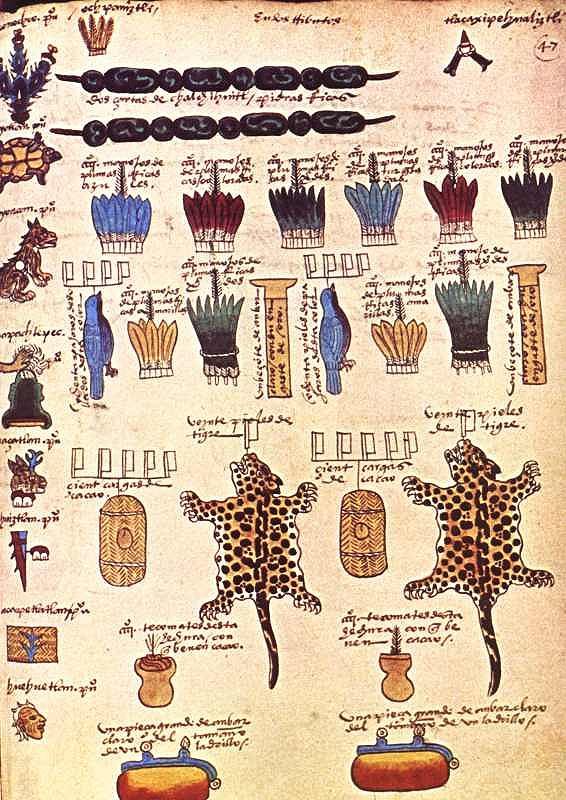

I first came across Cahill’s projection on a stamp issued in Mexico in 1964. The design of the stamp (see image) shows his world map, an octahedral whose eight faces have been flattened into a shape resembling a butterfly. Ever since then I have wondered why such an unusual map would be chosen for a Mexican stamp that commemorated the 10th Conference of the International Bar Association (IBA), held that year in Mexico City. Coming some 20 years after the cartographer’s death, it seems an unlikely choice. So far, all my efforts to find a link between Cahill, the IBA and Mexico have drawn a blank. (Note to readers: Help needed!)

Cahill’s butterfly map, like Buckminster Fuller’s later Dymaxion Maps (1943 and 1954) enabled all the continents to appear linked, and with reasonable fidelity to a globe. Cahill demonstrated this principle by also inventing a rubber ball globe which could be placed under a pane of glass and flattened into the “Butterfly” form. When removed, the map/globe reverted to its original shape.

Largely in honor of his cartographic innovation, Cahill was elected a Fellow of the Royal Geographical Society. In 1913 he started the Cahill World Map Company, but this company was not successful and his map has since been largely forgotten by most people.

But not by cartographer Gene Keyes! Except for Cahill himself, no follower of Cahill’s projection has ever been as dedicated as Gene Keyes, a former student of Buckminster Fuller. Keyes’ website is a mine of information about Cahill and his map projection, and is well worth reading.

Born in the UK, Bernard Joseph Stanislaus Cahill (18661944) was an architect, town planner and cartographer who moved to San Francisco, California, in 1888. He was an early proponent of the San Francisco Civic Center and designed that city’s Neptune Society Columbarium.

Cahill encountered some stiff obstacles in the many years it took him to develop his butterfly projection. For example, he lost all his initial drawings and papers in the disastrous San Francisco earthquake and fire of 1906. At least one major publisher signed a contract to publish the butterfly map as a wall map and in an atlas, but then failed to follow through.

Cahill’s world map used for world tours

Soon after its creation, Cahill’s butterfly map was used to illustrate a flying trip around the world, or circumaviation, proposed for the Panama Pacific International Exposition held in San Francisco in 1915. The map was exhibited at this exposition and won a gold medal for cartography. Some time later, the map was used by both the State of California and the City of Charleston to illustrate shipping routes.

In 1924, the American Express Company chose the map for use during a world tour aboard the Cunard ocean liner Laconia. According to Keyes, the map was prominently displayed on the Palm Deck of the ship and seen by Robert Ripley, a participant on the world tour, who later featured it in his Believe it or Not series.

Perhaps the closest Cahill came to seeing his map in more general use came in 1937, when the International Meteorological Committee apparently came within a single vote of adopting a version of his projection for all world weather charting.

No wonder, then, that in Keyes’ words, “Cahill should be seen in company with other pioneers such as Charles Babbage or Gregor Mendel, who died long before their efforts gained wider appreciation. As well, he antedates Buckminster Fuller, prophet of Spaceship Earth.”

Keyes goes on to note that, “Cahill was not merely an astute architect and cartographer, but, that like Fuller, his map expressed an underlying whole-earth philosophy much like themes which emerged 60 years later. Cahill used the term “geosophy” in that regard….” (And used it as early as 1912, well before the geographer J.K. Wright, commonly credited for having coined the term in 1947).

Will Cahill’s map ever catch on? The latest sign of renewed interest in Cahill’s projection comes from its adaptation by the New York Times as the basis for a series of 10 maps published in December 2011 illustrating the changing world of computing, communications and technology.

Keyes closes his account of Cahill’s map by quoting Ambrose Bierce, who in a letter to Cahill, wrote that, “The Butterfly Map is indubitably the right one, but it will be a long time before it gets into general use….”

Sadly, that has proved to be all too true, despite its inclusion in the design of a Mexican postage stamp.

Related posts using Mexican stamps for illustration:

- First map of Mexico on postage stamp

- Earliest landscapes on Mexican postage stamps

- A matter of scale: Mexico compared to Spain

- The rapid expansion of electricity provision in Mexico

- The geography of honey production in Mexico

- Tomato production in Mexico

- Mexico’s mega-biodiversity

- Bicycle manufacturing in Mexico

- Mexico’s long connection with the Philippines – exploration, seafaring and geopolitics

- Mexico’s major dams and reservoirs

- The story of Paricutín volcano in Michoacán