The Mexican holiday of Cinco de Mayo (5 May) commemorates the Battle of Puebla, fought on May 5, 1862. The battle marks Mexico’s best-known military success since its independence from Spain in 1821.

Today, in a curious example of cultural adaptation, the resulting holiday is celebrated far more widely in the USA than in Mexico.

The background to the Battle of Puebla

The nineteenth century in Mexico was a time of repeated interventions by foreign powers, including France, Spain, Britain and the USA, all of which hatched or carried out plans to invade.

The first French invasion, in 1838, the so‑called Pastry War, lasted only a few days. A decade later, US troops entered Mexico City, and Mexico was forced to cede Texas, New Mexico and (Upper) California, an area of 2 million square kilometers, about half of all Mexican territory, in exchange for 15 million pesos.

The first French invasion, in 1838, the so‑called Pastry War, lasted only a few days. A decade later, US troops entered Mexico City, and Mexico was forced to cede Texas, New Mexico and (Upper) California, an area of 2 million square kilometers, about half of all Mexican territory, in exchange for 15 million pesos.

A new constitution in 1857 provoked an internal conflict, known as the Reform War (1858‑60), between the liberals led by Benito Juárez, who supported the new constitution, and the conservatives. The War decimated the country’s labor force, reduced economic development and cost a small fortune. Both sides had serious financial problems. At one point in this war, the liberals reached an agreement with the USA to be paid four million pesos in exchange for which the USA would receive the “right of traffic” across the Isthmus of Tehuantepec “in perpetuity”. Fortunately, this treaty was never ratified by the US Senate.

The financial crisis deepened, eventually leading Mexico to suspend all payments on its foreign debt for two years. The vote was approved by the Mexican Congress by a single vote. The foreign powers involved were furious; in 1861, Britain, France and Spain decided on joint action to seize the port of Veracruz on Mexico’s Gulf coast and force Mexico’s government to pay. The UK and Spain quickly agreed terms and withdrew their military forces, but the French decided to stay.

The French are confident of victory

France’s emperor, Napoleon III (Louis Napoleon Bonaparte) had grand ambitions and envisaged a Mexican monarchy. To this end, he decided to place Austrian archduke Maximilian von Habsburg as his puppet on the Mexican throne. The French Army moved inland from Veracruz and occupied the city of Orizaba. The French commander was supremely confident that his forces could crush any opposition. (Following their defeat at Waterloo in 1815, no-one had beaten the French in almost fifty years.) The Commander, Charles Ferdinand Latrille, the Count of Lorencez, confidently boasted that, “We are so superior to the Mexicans in race, organization, morality and devoted sentiments that I beg your Excellency [the Minster of War] to inform the Emperor that as the head of 6,000 soldiers I am already master of Mexico.” (Quoted in “Betterment for Whom? The Reform Period: 1855‑1875” by Paul Vanderwood, chapter 12 of The Oxford History of Mexico (edited by Michael C. Meyer and William H Beezley, O.U.P. 2000).

Mexican resistance

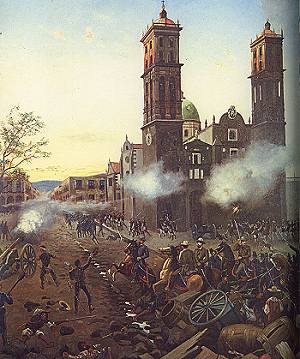

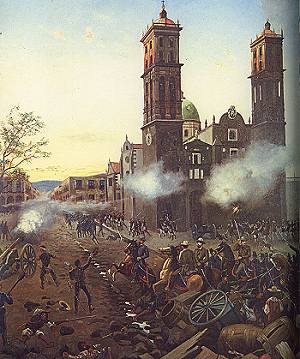

Marching towards Mexico City, the French needed to secure Puebla, which was defended by 4,000 or so ill‑equipped Mexican soldiers. Ironically, given the eventual outcome, many of the defenders were armed with antiquated weapons that had already beaten the French at Waterloo, before being purchased in 1825 by Mexico’s ambassador to London at a knock-down price! The Mexican forces, the Ejército de Oriente (Army of the East) were commanded by General Ignacio Zaragoza, a Texas‑born Mexican. Zaragoza dug his forces into defensive positions centered on the twin forts of Loreto and Guadalupe.

The events of 5/05

On the 5 May 1862, Zaragoza ordered his commanders to repel the invaders at all costs. Mexicans received unexpected help from the weather. After launching a brief artillery bombardment, the French discovered that the ground had become so muddy from heavy unseasonable downpours that maneuvering their heavy weapons was next to impossible.

Bullets rained down on them from the Mexican troops that occupied the higher ground near the forts. At noon, the French commander ordered his troops to charge the center of the Mexican lines. But the lines held strong, and musket fire began to take its toll. Successive French attacks were rebuffed. The Mexican forces then counter‑attacked, spurred on by well-organized cavalry, led by Porfirio Díaz who would subsequently become President of Mexico.

As the afternoon wore on, and the smoke began to clear, it became apparent that the defenders of Puebla had successfully repelled the European invaders. The French troops fled back to Orizaba before retreating back to the coast to regroup. A crack European army had been soundly defeated by a motley collection of machete‑wielding peasants from the war‑torn republic of Mexico….

A few days later, on 9 May, President Benito Juárez declared that the Cinco de Mayo would henceforth be a national holiday.

Aftermath: the French return with reinforcements

Back in Paris, Napoleon was enraged. He ordered massive reinforcements and sent a 27,000-strong force of French military might to Mexico. This strengthened French army (under Marshal Elie Forey) took Mexico City in 1863, forcing Benito Juárez and his supporters to flee. Juárez established himself in Paso del Norte (now El Paso) on the US border, from where he continued to orchestrate resistance to the French presence. Supported by the conservatives, Maximilian finally ascended to the throne in May 1864. By this time, in the USA, the Unionists had taken Vicksburg, and the US government was considering its position. In May 1865, General Philip Sheridan led 50,000 US soldiers to ensure that French troops did not cross the Mexico‑USA border. Diplomatic pressure for a French withdrawal intensified and Napoleon III finally agreed to remove his troops in February 1866.

After the French had departed, President Juárez reestablished Republican government in Mexico, and put Maximilian on trial, ending an extraordinary period in Mexican history.

The significance of 5/05

With the passing of time, the Cinco de Mayo has assumed added significance because it marks the last time that any overseas power was the aggressor on North American soil.

In Mexico, the Cinco de Mayo is still celebrated with lengthy parades in the state and city of Puebla, and in neighboring states like Veracruz. There is at least one street named Cinco de Mayo in almost every town and city throughout the country.

In the USA, the Cinco de Mayo has been transformed into a much more popular cultural event, and one where many of the revelers think it commemorates Mexican Independence, not a battle. (Mexico’s Independence celebrations are in mid-September each year).

Many communities in the USA, especially the Hispanic communities, use Cinco de Mayo as the perfect excuse to celebrate everything Mexican, from drinks, music and dancing, to food, crafts and customs. The Cinco de Mayo has become not just another day in the calendar, but a very significant commercial event, one now celebrated with much greater fervor north of the border than south of the border.

Where to go to see more — Texas

General Ignacio Zaragoza died on September 8, 1862, only a few months after the Battle of Puebla. In 1960, the General Zaragoza State Historic Site was established in his birthplace, near Goliad, Texas, to commemorate his famous victory. In Zaragoza’s time, the town was known as La Bahía del Espíritu Santo.

Where to go to see more — Puebla

The Guadalupe and Loreto forts are in parkland, about 2 km north‑east of Puebla city center. The Fuerte de Guadalupe is ruined. The Fuerte de Loreto became state property in 1930. It is now a museum, the Museum of No Intervention (Museo de la No Intervención), complete with toy soldiers. The park has an equestrian statue of General Zaragoza and is the setting for the Centro Civico 5 de Mayo, with its modern museums, including the Regional Museum (history and anthropology), the Natural History Museum and the Planetarium (IMAX screen).