A case study of the Cabo Cortés tourism megaproject in Baja California Sur

The Cabo Cortés megaproject is planned for the area near Cabo Pulmo on the eastern side of the Baja California Peninsula. Cabo Pulmo, a village of about 120 people, is about an hour north of San José del Cabo, and on the edge of the Cabo Pulmo National Marine Park.The area is a semi-arid area, where water provision is a serious challenge.

The Cabo Cortés megaproject is planned for the area near Cabo Pulmo on the eastern side of the Baja California Peninsula. Cabo Pulmo, a village of about 120 people, is about an hour north of San José del Cabo, and on the edge of the Cabo Pulmo National Marine Park.The area is a semi-arid area, where water provision is a serious challenge.

The megaproject is centered on an extensive belt of mature sand dunes which fringe the coast immediately north of Cabo Pulmo.

The megaproject has been in the planning stages for several years, but Mexico’s federal Environment and Natural Resources Secretariat (Semarnat) recently gave Spanish firm Hansa Urbana the green light to begin construction. The controversial plans for Cabo Cortés involve building on the virgin sand dunes, and will undoubtedly have adverse impacts on the small village of Cabo Pulmo and the ecologically-sensitive Cabo Pulmo National Marine Park.

The Semarnat decision provoked the immediate ire of Greenpeace and other environmental campaigners, as well as local residents who fear being displaced from the small village of Cabo Pulmo by a proposed marina.

The value of the Cabo Pulmo National Marine Park

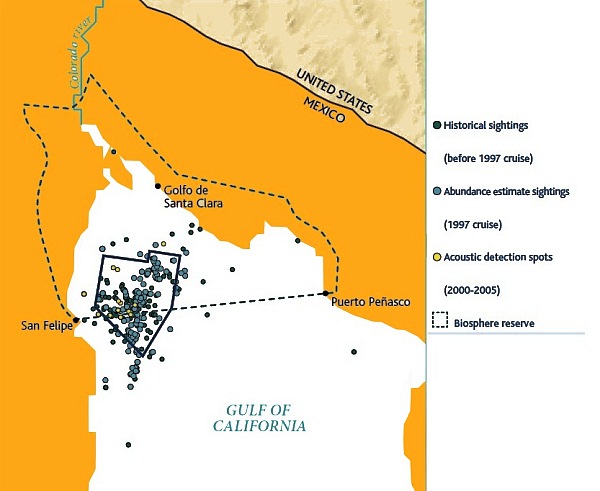

Jacques Costeau, the famous ocean explorer, once described the Sea of Cortés as being the “aquarium of the world.” This area of the Sea has been protected since 1995 and is now designated a National Marine Park. It was declared a “Natural Patrimony of Mankind” by UNESCO in 2005. The protected area, ideal for diving, kayaking and snorkeling, covers 71 sq. km of ocean with its highly complex marine ecosystem. Dive sites include underwater caves and shipwrecks.

The biological productivity of the Marine Park is amazing. Since the National Marine Park was established, the number and size of fish inside the park boundaries have increased rapidly. Studies show that the number of fish has more than quadrupled since 1995, owing to the exceptional productivity of the offshore reef area. The park is an outstanding example of the success of environmental protection efforts.

Cabo Pulmo is on the Tropic of Cancer, about as far north as coral usually grows. The water temperatures vary though the year from about 20 to 30 degrees C (68 to 86 degrees F). The seven fingers of coral off Cabo Pulmo comprise the most northerly living reef in the eastern Pacific. The 25,000-year-old reef is the refuge for more than 220 kinds of fish, including numerous colorful tropical species. Divers and snorkelers regularly report seeing cabrila, grouper, jacks, dorado, wahoo, sergeant majors, angelfish, putterfish and grunts, some of them in large schools.

The tourism megaproject

The project involves an area of 1,248 hectares (3,000 acres). Swathes of land will be cleared for two 18-hole golf courses. Water provision will require the extraction of 4.5 million cubic meters of groundwater a year from the Santiago aquifer, and the construction of 17 kilometers of aqueducts. The planned marina has 490 berths. When complete, the megaproject will offer more than 27,000 tourist rooms, almost as many as Cancún has today, and almost three times as many as currently in nearby Los Cabos. It is estimated that Cabo Cortés will generate 39,000 metric tons of solid wastes a year (about 2 kg/person/day).

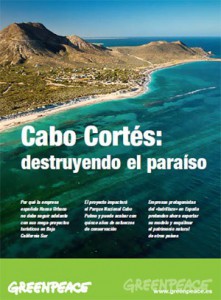

Cover of Greenpeace’s position paper on Cabo Cortés

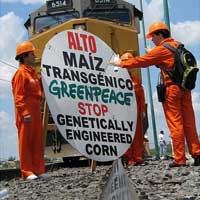

NGOs oppose Cabo Cortés

When challenged about the legality of granting permission for a project which will impact the Marine Park, Semarnat officials have claimed that the ecological criteria in Semarnat regulations are “suggestive” rather than “obligatory”.

Several NGOs have already launched protest campaigns. Alejandro Olivera is spearheading Greenpeace’s opposition to Semarnat’s decision. He has described the decision as “erroneous” and claims that the megaproject is “not congruent with the prevailing ecological regulations for the region, given that the construction of the marina is in direct contravention of the Los Cabos Ecology Plan which covers this region. The plan expressly prohibits any construction on shoreline dunes. Semarnat maintains that its authorization of a marina and elevated walkways will not affect the “structure or functioning of the area’s sand dune system”.

Olivera emphasizes that Greenpeace is not opposed to tourism as a development strategy, but that it believes in sustainable (responsible) tourism that respects the area’s carrying capacity. Meanwhile, a Greenpeace Spain spokesperson claims that the resort development model of Hansa Urbana, is fundamentally flawed and outdated, and that, when implemented in Spain, it resulted in unacceptable social and environmental costs.

Amanda Maxwell of the Natural Resources Defence Council (NRDC) has written a good summary of why the Semarnat decision should be opposed, entitled “Approval of the Cabo Cortés resort complex–next to the healthiest coral reef in the Gulf of California–is a huge step backward for Mexico“

The 120 or so local residents who live in Cabo Pulmo village also oppose the plan and have formed an NGO called Cabo Pulmo Vivo. The existing village, which has no street lights, is a haphazard collection of homes and small businesses, including dive shops, stores and restaurants.

Cabo Pulmo Vivo organized on online petition calling for the Semarnat permits to be revoked.

Personal view, written following a visit in 2008

“We arrive in Cabo Pulmo as the sun is setting, relieved to finally find the end of the initially paved, then dirt, access road, which has been bounded by barbed wire ever since we caught our last clear views of the coast near La Ribera. At intervals behind the barbed wire are warning signs making it very clear that the land either side of the road is private.

Over a beer with Kent Ryan, the owner of Baja Bungalows, our base for the next few days, I learn that the newly erected fences mark the beginning of a major development of the coast immediately outside the National Marine Park. When I eventually got a chance to examine the masterplan, I can only say that I’m glad we visited Cabo Pulmo in early 2008 before this coast is changed for ever.” (Tony Burton in MexConnect)

Further information:

For an exceptionally informative series of papers (in Spanish) on all aspects of tourism and sustainability in Cabo Pulmo, see Tourism and sustainability in Cabo Pulmo, published in 2008.

Another valuable resource (also in Spanish) is Greenpeace Spain’s position paper entitled Cabo Cortés, destruyendo el paraíso (“Cabo Cortés: destroying paradise”) (pdf file)