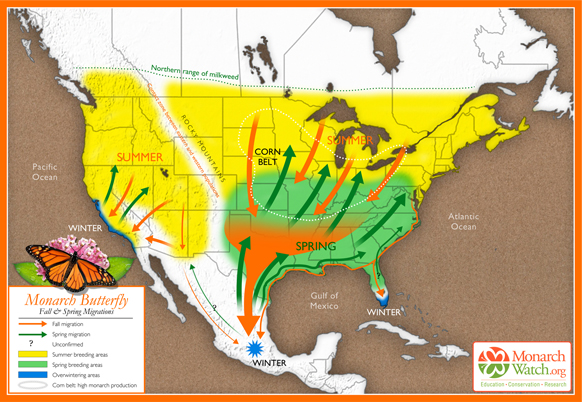

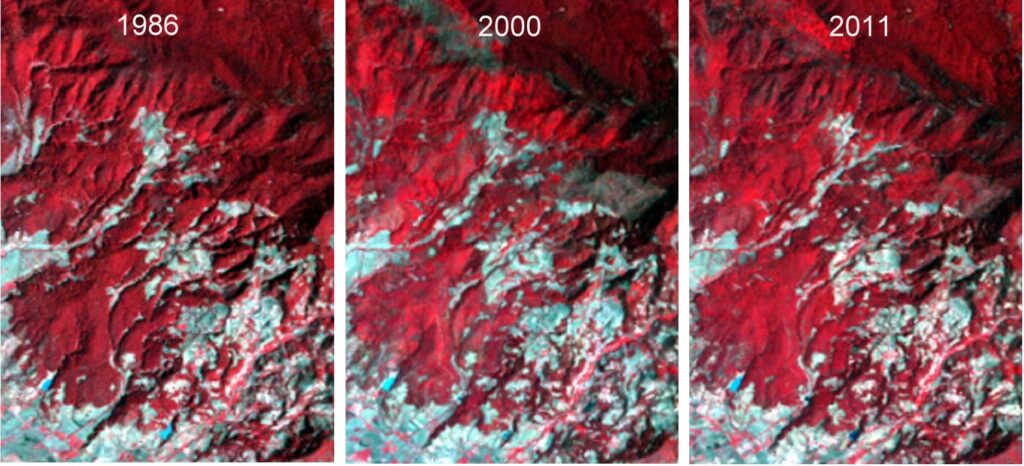

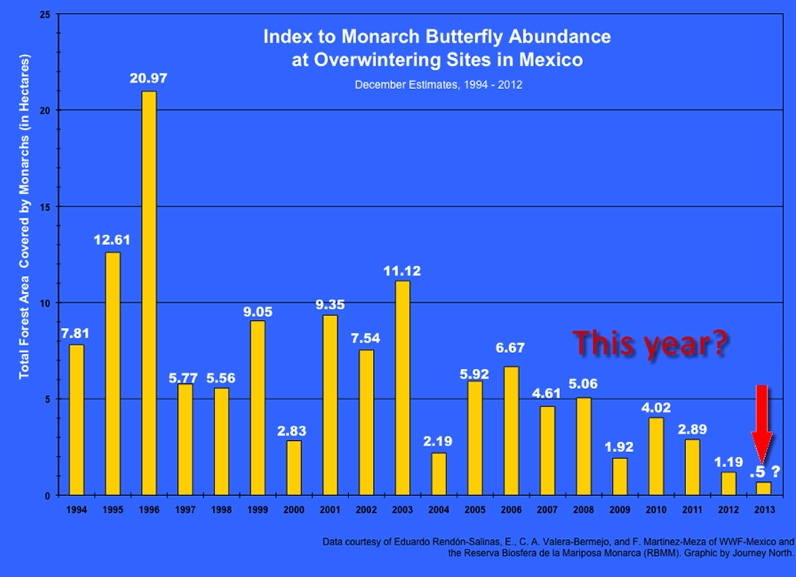

Most monarch butterflies never migrate, but one generation of the North American monarch population undertakes an annual, long distance migration, a journey without parallel in the insect world. Every winter, some one hundred million monarch butterflies fly south into Mexico from the U.S. and Canada. They congregate and spend the winter in a dozen localities high in the temperate pine and fir forests of the states of México and Michoacán.

Where do the Monarchs overwinter?

The exact sites where the butterflies overwinter were only found in the mid 1970s after a search of nearly forty years. Scientists are still unable to explain all the details of this enigmatic annual migration, but their unexpectedly sophisticated navigational ability seems to rely on an incredible innate accuracy in pinpointing their position by using their eyes and antennas to measure the angles of the sun’s rays, compensating for time of day, and ensuring they continue to fly in a southerly direction towards the state boundary separating Michoacán from the State of México.

How fast can they fly?

The tagging of butterflies has proven that they make the 2500 kilometer trip each way at an impressive average speed of 20 km/h, with maximum speeds of up to 40 km/h (25 mph). Monarchs don’t fly at night, partly because they need daylight to navigate and partly because they fly best when sunlight has warmed their wings, like miniature solar panels, raising their body temperatures some 10 to 15 degrees Celsius above ambient air temperatures.

The butterflies are energy-efficient flyers, making regular nectar stops along the way to refuel. One third of their dry body weight is energy-giving fat but far from losing weight on their exhausting journey south, they actually appear to gain it! There are still many mysteries about the monarchs but they certainly provide one of the most amazing natural spectacles to be seen anywhere on earth. Millions of orange butterflies, with black and white-spotted wings, whether flying overhead or, as on cooler days, clinging apparently lifeless to the grey-green fir trees in such numbers that the trees appear to be in blossom, are an absolutely unforgettable sight.

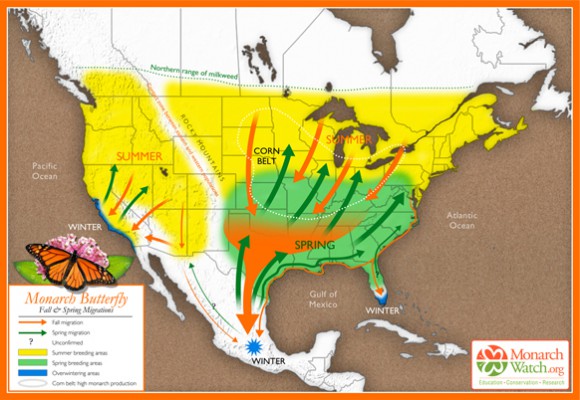

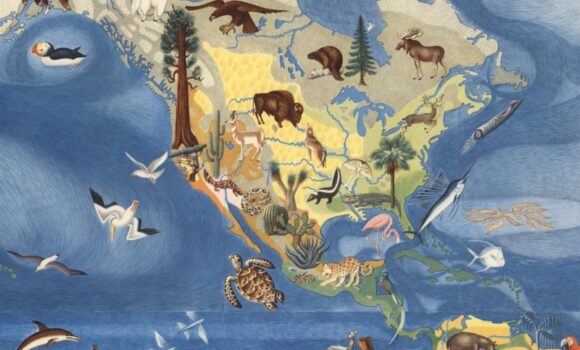

Based on original map design created by Paul Mirocha (paulmirocha.com) for Monarch Watch.

The journey south

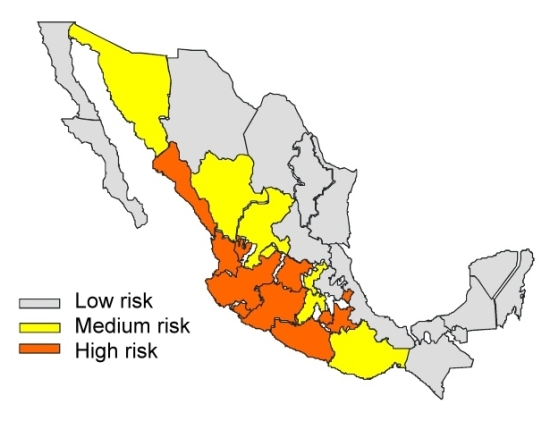

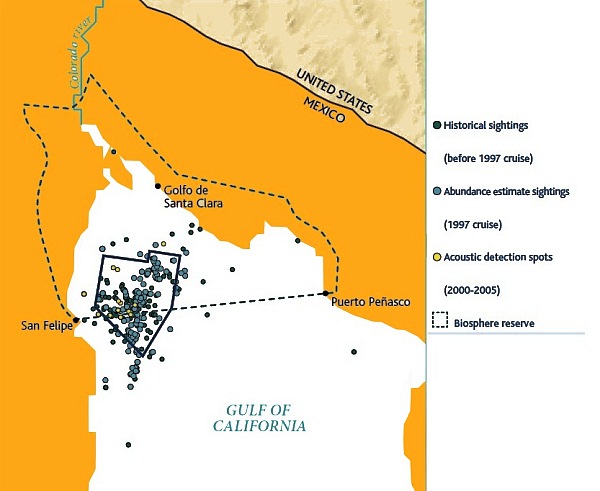

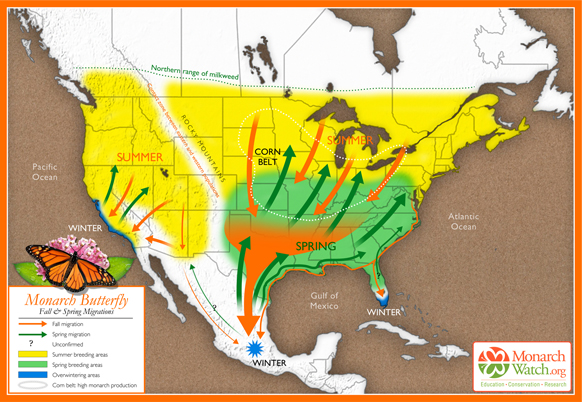

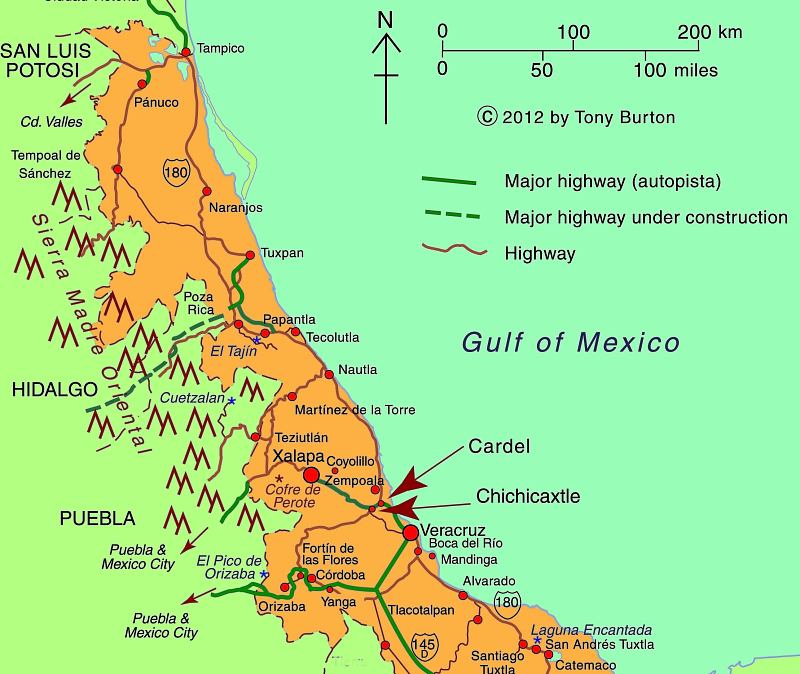

In September and October, as temperatures in the U.S. and Canada fall, and food supplies become scarce, the monarchs fly south in small groups. Some of these groups fly only as far as Florida or western California where they spend their winters in milder conditions. But many of the small groups from east of the Continental Divide eventually coalesce and fly much further south, as far as Mexico, arriving en masse in the state of Michoacán towards the end of November.

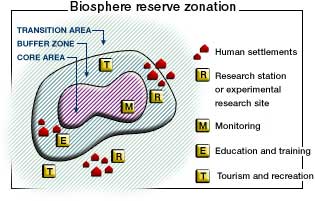

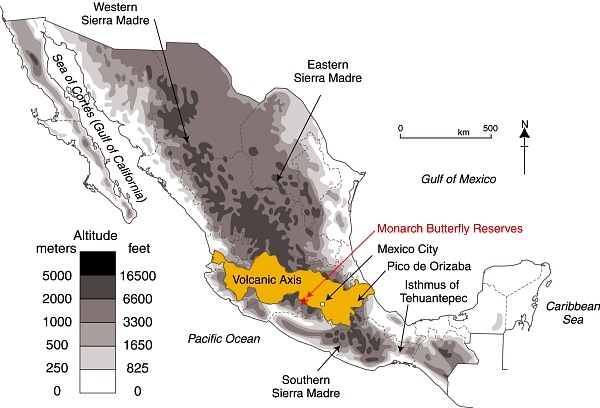

This migratory group is comprised of as many as 120 million individuals and spends the winter in semi-dormancy, on the pine and oyamel (sacred fir, Abies religiosa) trees found at elevation of about 3050 meters (10,000 feet) along Mexico’s central Volcanic Axis. Until spring comes, in March or April, these butterflies cling to the branches and trunks of the trees, enjoying temperatures between 10 and 16 degrees Celsius, protected from cold northerly winds. Their metabolism slows down in these low temperature, low oxygen conditions and they exhibit movement only on warm, sunny, days.

The generation that flies into Mexico does not mature sexually until the following spring. In February and March, the best months to see them, early spring sunlight begins to penetrate the groves of fir trees, temperatures begin to rise and the forest floor slowly comes alive with new plant growth. The butterflies, having successfully overwintered the worst weather, unfurl their wings and flutter about in search of food and water. As they regain their strength, so they become sexually mature and the mating process starts.

The journey north

After mating, the butterflies begin to leave the reserves, flying back towards the north. Five days later, in northern Mexico and the southern U.S., each female lays two to three hundred eggs on the underside of milkweed leaves. They first check (by smell and touch) that no eggs have already been laid there, and then space their eggs in such a way so as to ensure that each larva that hatches two to three days later will have an adequate supply of food. The larvae grow quickly, changing their skins five times before becoming pupae. After a further two weeks, butterflies emerge, and fly northwards. Each generation of monarchs probably acquires a different chemical “blueprint”, based on the exact species of milkweed it eats, giving it the information it needs to know where to fly. Eventually, by April, the northernmost butterflies reach Canada.

No individual butterfly completes the entire 5000 kilometer round trip. Most of those that fly south die soon after mating in spring (with males often dying in the reserves and never starting their homeward trip), while those who head north cannot hope to survive long into the summer, when normal reproductive cycles, each lasting from four to six weeks, are reestablished.

The last generation of each summer, perhaps prompted by shorter days, soon departs on the next wave of mass migration to Mexico. Those from furthest north will cross the Great Lakes on their return in a single day’s flight, an impressive feat in its own right. They have been spotted flying south at heights up to 1500 meters and exploit thermals to gain height and save energy.

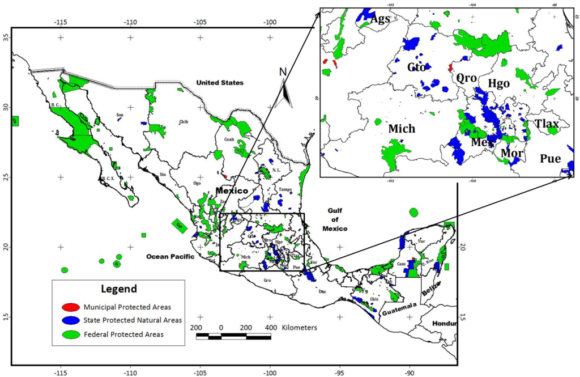

Where to see Monarch Butterflies

Several monarch reserves are open to the public each year. Each has its own distinctive character. Two of the most important reserves are close to the town of Angangueo. Sierra Chincua, north of the town, is the site where the first Canadian-tagged monarch was found in the mid 1970s. This is also where I first saw the butterflies, in 1980, while looking for a potential site for geography fieldwork. It was a serendipitous discovery, and led to me being mistaken for a BBC reporter, but that’s another story!

Angangueo. Sketch by Mark Eager; all rights reserved.

The most accessible reserve open to the public is El Rosario, south of Angangueo, where there are dozens of souvenir stalls and rustic snack stands—don’t miss sampling the delicious hand-made blue-corn tortillas. The narrow trails in the sanctuary, with information boards at regular intervals, wind steeply several hundred meters uphill, reaching a maximum altitude of 3050 meters. This altitude can cause some shortage of breath and air temperatures are generally low, so be sure to bring a sweater.

El Rosario can be reached from either Angangueo (steeper but more direct approach) or Ocampo. Anyone driving their own vehicle to El Rosario is advised to use the route via San Felipe (on Highway 15) and then Ocampo. From Ocampo any vehicle with adequate ground clearance, including the local taxis, can negotiate the fourteen kilometers to the monarch sanctuary parking lot.

The San Felipe-Ocampo junction on Highway 15 is marked by a line of fruit and soft-drink stalls, many of which in season sell delicious granadas (pomegranates). Also at this junction is an interesting sixteenth century church which, until as recently as 1995, had tombstones in its atrium, unusual in Mexico. Normally, the Spanish buried their dead as far away from the churchyard as possible, presumably to avoid the risk of disease.

Want to read more?

This post is based on chapter 36 of my “Western Mexico: A Traveler’s Treasury” (link is to Amazon’s “Look Inside” feature), also available as either a Kindle edition or Kobo ebook.

Related posts:

![birds-ibas-2 Important Bird Areas in Mexico [Birdlife.org]](http://geo-mexico.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/07/birds-ibas-2.jpg)