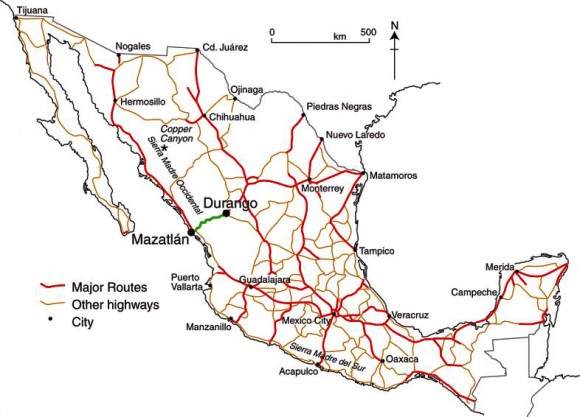

Mexico’s road network is heavily used, accounting for over 95% of all domestic travel. On a per person basis, Mexicans travel an average of 4500 km (2800 mi) by road each year.

In this post, we try to answer several general questions relating to the geography of road transport in Mexico.

How many cars are there?

On average there are about seven people per car in Mexico, compared to about six in Argentina, ten in Chile and less than two in the USA and Canada. There are far more cars in urban areas with their many businesses, taxis and wealthy residents. In poor rural parts of southern Mexico, private car ownership is quite rare.

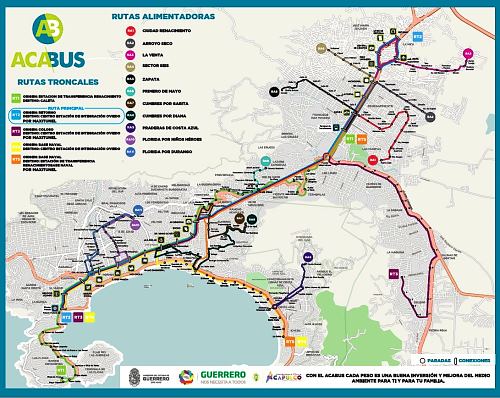

Is there an efficient bus system?

Mexico also has an inter-city bus system that is one of the finest in the world. The nation’s fleet of more than 70,000 inter-city buses enables passengers to amass almost half a trillion passenger-km per year.

Where are Mexico’s vehicles made?

Almost all the vehicles on Mexico’s roads were built in Mexico. Mexico’s automobile-manufacturing sector produces about 2.2 million vehicles a year but the majority of production (about 1.8 million vehicles each year) is for export markets. Mexico is the world’s 9th largest vehicle maker and 6th largest vehicle exporter. In recent years, the relaxation of strict import regulations has resulted in more vehicles being imported into Mexico; many of them are luxury models not currently made in Mexico.

The major international vehicle manufacturers with plants in Mexico include Volkswagen, Ford, Nissan, GM, Renault, Toyota and Mercedes-Benz. Mexican companies include Mastretta, which specializes in sports cars, and DINA, a manufacturer of trucks, buses and coaches.

For more information about vehicle manufacturing in Mexico:

Where are Mexico’s vehicles?

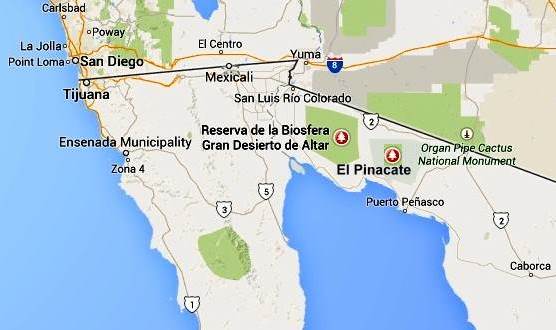

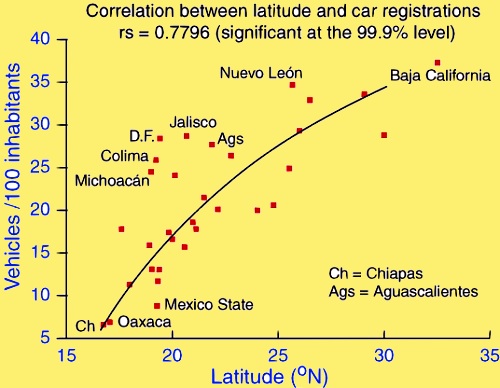

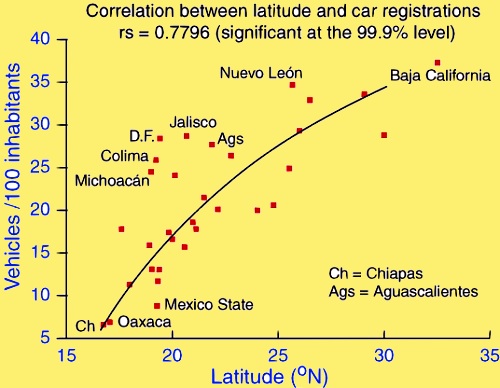

Mexico has about 20 million registered vehicles, about one for every five persons (2005). Which areas have the most and least vehicles? It turns out that the northernmost state, Baja California, has the most with 37 registered vehicles per 100 people. The southernmost states, Chiapas and Oaxaca, have about one sixth as many with 6.6 and 6.9 respectively. In fact there is a very strong statistical relationship between latitude and vehicles (see graph). How can this be?

We are not suggesting a direct causal relationship. Many factors are interrelated. First, the states in the north tend to be wealthier; the Spearman rank correlation for GDP/person and latitude is 0.58. Vehicle ownership is closely related to GDP/person (rs = 0.59). Both these correlations are significant at the 99% level.

We are not suggesting a direct causal relationship. Many factors are interrelated. First, the states in the north tend to be wealthier; the Spearman rank correlation for GDP/person and latitude is 0.58. Vehicle ownership is closely related to GDP/person (rs = 0.59). Both these correlations are significant at the 99% level.

In addition, northern states are close to the USA, a vehicle-oriented society. However, there are some anomalies to the general pattern. The very wealthy Federal District has 50% more vehicles than would be expected from its latitude alone. States with many migrants, such as Jalisco and Michoacán, also have more vehicles than expected given their latitude. An added complication is that more than a million foreign-plated cars in Mexico (imported temporarily by returning migrants or foreigners) are not included in these figures.

How many road accidents are there in Mexico?

Mexico’s National Council for Accident Prevention estimates that there are 4 million highway accidents each year in Mexico. The latest figures (for 2010) show that there were 24,000 fatalities as a result of these accidents, with 40,000 survivors suffering some lasting incapacity. These figures include some of the 5,000 pedestrians struck by vehicles each year. Traffic accidents are currently the leading cause of death for those aged 5-35 in Mexico, and the second cause of permanent injury for all ages.

Why are there so many accidents?

Driver education plays a major role in road safety. Part of Mexico’s problem is the low budget it allocates each year for road safety—just US$0.40 compared to more than $3.00/person in the USA, more than $7.00/person in Canada and up to $40.00/person in some European countries.

It is no surprise that a high percentage of drivers involved in traffic accidents in Mexico have alcohol in their system. This is one of the reasons why accidents are statistically more frequent in the evenings from Thursday to Saturday. One study reported that as many as 1 in 3 of drivers in Guadalajara was under the influence of alcohol while driving, and 1 in 5 of Mexico City drivers.

Driving without insurance is common in Mexico; according to insurance companies, only 26.5% of Mexico’s 30.9 million vehicles have any insurance.

Related posts: