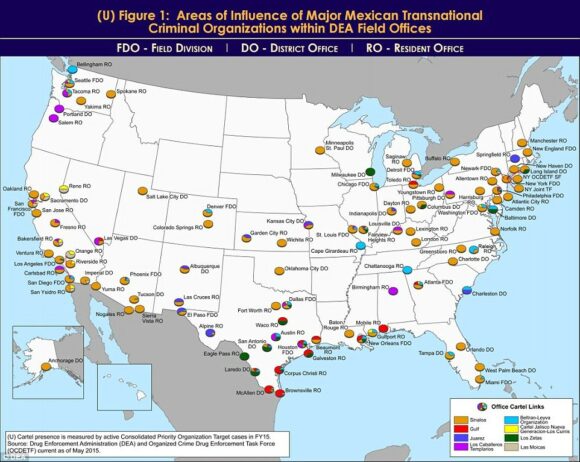

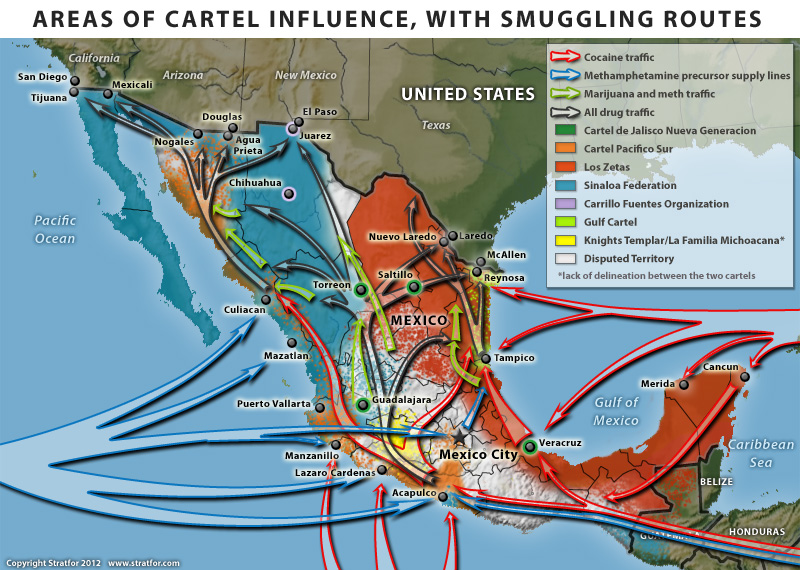

An unclassified DEA Intelligence Report from a year ago has just resurfaced on my desk. Entitled United States: Areas of Influence of Major Mexican Transnational Criminal Organizations, it includes two particularly interesting maps.

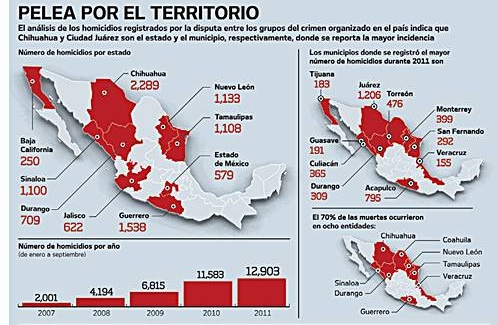

The report states that “Mexican transnational criminal organizations (TCOs) pose the greatest criminal drug threat to the United States; no other group is currently positioned to challenge them. These Mexican poly-drug organizations traffic heroin, methamphetamine, cocaine, and marijuana throughout the United States, using established transportation routes and distribution networks. They control drug trafficking across the Southwest Border and are moving to expand their share, particularly in the heroin and methamphetamine markets.”

As of May 2015, the DEA identified the following cartels that operate cells within the USA: the Sinaloa Cartel, Gulf Cartel, Juarez Cartel, Knights Templar (Los Caballeros Templarios or LCT), Beltran-Leyva Organization (BLO), Jalisco New Generation Cartel (Cartel Jalisco Nueva Generacion or CJNG), Los Zetas, and Las Moicas.

The maps reflect “data from the Organized Crime Drug Enforcement Task Force (OCDETF) Consolidated Priority Organization Target (CPOT) program to depict the areas of influence in the United States for major Mexican cartels.”

Figure 1 (click map to enlarge) shows the distribution of DEA Field Offices. The pie chart for each office shows “the percentage of cases attributed to specific Mexican cartels in an individual DEA office area of responsibility”.

“Since 2014, the Arellano-Felix Organization, LCT, and the Michoacán Family (La Familia Michoacán LFM) cartels have been severely disrupted, which subsequently led to the development of splinter groups, such as, “La Empresa Nueva” (New Business) and “Cartel Independiente de Michoacan” (Independent Cartel of Michoacan) representing the remnants of these organizations.”

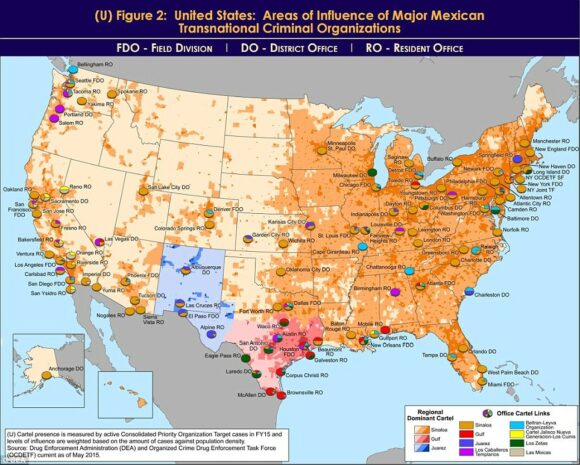

Figure 2 (below) shows the dominant transnational criminal organization (TCO) in each domestic DEA Field Division, relative to other active TCOs in the same geographic territory. The map includes population density shading which “is intended to depict potential high density drug markets that TCOs will look to exploit through the street-level drug distribution activities of urban organized crime groups/street gangs.”

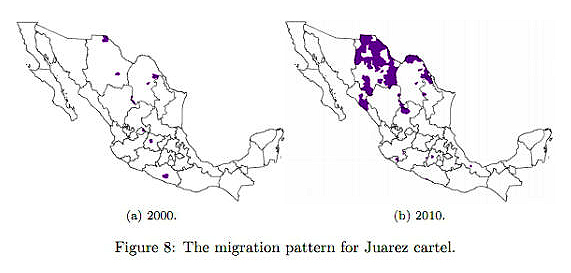

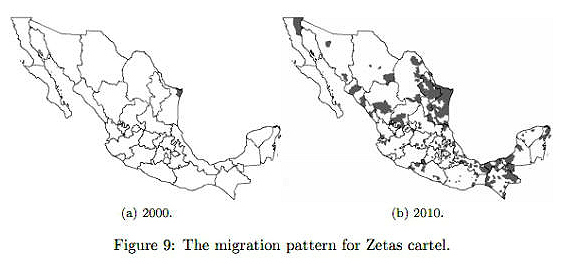

“The Sinaloa Cartel maintains the most significant presence in the United States. They are the dominant TCO along the West Coast, through the Midwest, and into the Northeast. While CJNG’s presence appears limited to the West Coast, it is a cartel of significant concern, as it is quickly becoming one of the most powerful organizations in Mexico, and DEA projects its presence to grow in the United States over the next year. In contrast, Mexican cartels such as the Gulf, Juarez, and Los Zetas hold more significant influence closer to the Southwest Border, but as shown on the map, their operational capacity decreases with distance from the border.”

Other, smaller, “splinter groups from the disrupted LCT organization continue to traffic drugs from the Michoacán, Mexico area into the United States. The BLO, former transportation experts for the Sinaloa Cartel, is most active along the East Coast and is also responsible for the majority of heroin in the DEA Denver area of responsibility. Las Moicas is a Michoacán-based organization with former LFM links, but remains a regional supplier in California and operate on a smaller scale relative to other major Mexican TCOs.”

Related posts:

- The geography of Mexico’s drug trade: an index page (Mar 2016)

- How much drugs money is laundered in Mexico each year? (Apr 2012)

- Purity of illicit drugs declines with distance from the Mexico-USA border (Mar 2011)

- How might the USA adjust to “narco-refugees” from Mexico? (Jan 2012)

- How a migration channel from Mexico explains Denver’s heroin delivery system (May 2015)