The following account of Mexico’s traditional (folkloric) and introduced musical instruments consists of extracts from an article by Andrea Teter. [1]

Pre-Columbian instruments

Archaeologists have noted the existence of more than 1,400 musical instruments used in pre-Columbian Mexico and Central America. These were used primarily for religious, and healing rituals and for ceremonies, but also for war, dances, fiestas and entertainment. Some of these instruments, primarily the huehuetl, and teponaztli, both percussion, and the tlapitzalli, a four-hole flute, were considered divine or endowed with supernatural powers, say Mexican archeologists, and were worshiped as idols.

The Mexica (Aztecs) used flutes and trumpets made of clay, bamboo and metal. Drums, including the ayotl, made of tortoise shells, and other percussion instruments were used extensively. The huehuetl was the principal drum used by the Mexica and was made from animal skin stretched over a hollowed-out tree trunk. The teponaztli was made from hollowed-out trees or dried gourds, and sometimes gold and silver, with grooves or tongues cut into the top. Rich and varied tones are produced when played with small mallets. Pre-Columbian musicians also used cymbals, maracas, bells and even stones to produce their music.

The Youtube clip below is one interpretation of what some of Mexico’s indigenous musical instruments may have sounded like when played:

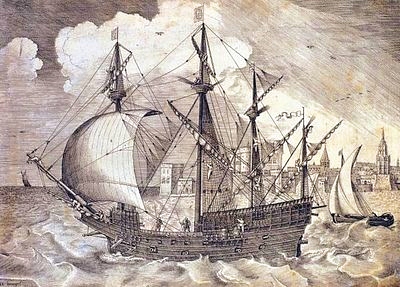

Europeans arrive

With the invasion of the Spanish, these musical instruments were immediately used to help convert the indigenous population to Christianity, while the Conquistadors began introducing European musical methods and instruments. A Franciscan missionary, Pedro de Gante, established the first music school in Mexico in 1523 and trained students in the construction and playing of European instruments.

Little by little, all of the European instruments were introduced to Latin America, starting in the 16th century with organs, guitars, harps and flutes, and later followed by the violins, trumpets, mandolins and accordions. Especially important and influential were guitars, which rose to prominence in the seventeenth century, as an easier-to-play alternative to the lute.

Six-string guitars, viheulas, became extremely popular in Mexico with other instruments of the same family also put into general use: five-string charangos, tiples, or treble guitars, and a large 12-string guitar similar to a bass, the bajo sexto.

Another string instrument that became popular in Mexico was the mandolin. The mandolin, which comes from Southern Italy, is the most recent development of the lute family. It was popularized in Mozart’s “Don Giovanni” and Verdi’s “Othello”.

The salterio, originally from Egypt, is a stringed instrument a little larger than a briefcase with a sound resembling a harpsichord and a playing method resembling a steel guitar or autoharp. The musician plucks the 97 strings while it rests on his knees; the sound is unique and quite beautiful.

Once the Spanish began importing slaves from Africa, these blacks began constructing marimbas, which imitated the African xylophone. As early as 1545, a Spanish scribe in the state of Chiapas wrote of an instrument of eight wood bars played with heavy sticks by the local natives at tribal ceremonies. The modern sophisticated Mexican marimbas was developed by Chiapas musician Corazon Borraz, who in 1896 brilliantly added a second row of half-tone bars to the common single row (like a piano’s black keys) adding to the musical scope of the original instrument, allowing it to play more complex music.

Today, a concert marimba can be three meters long, have 70 keys and weigh more than 55 kilos. This grand instrument demands four musicians; the bass man at the wide end with two sticks or baguetas having small rubber balls on the striking tips. This end has long resonance boxes hanging below the sound keys. Then the harmonics man with one or two sticks in each hand above shorter resonance boxes. Then comes the melody maker and leader, wielding two sticks per hand; then the narrow end controlled by the treble master, a stick in each hand producing counterpoint to the melody. Talk about a compact orchestra!

The variety of instruments Mexican musicians and composers have access to has resulted in a distinctive music for this country. At least one Mexican composer, Carlos Chavez, has gained international fame with his integration of Mexican pre-Hispanic instruments in his works such as “Sinfonia India,” “Xochipilli” and “Macuilxochitl.”

Some Mexican composers have been even more innovative. For example, Julián Carrillo (nominated for the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1950), one of Mexico’s top violinists, invented a microtonal music system known as Sonido 13. The system became sufficiently famous that Carrillo’s birthplace in the state of San Luis Potosí felt obliged to rename itself Ahualulco del Sonido 13: an interesting place to visit for any geographers interested in microtonal music! Ahualulco del Sonido 13 is located 39 kilometers northwest of the city of San Luis Potosí. Leaving that city, first follow federal highway 49 towards Zacatecas and then turn north on the road signed Charcas.

- Listen to a 12-minute sample mp3 of Sonido 13: Balbuceos (“Babblings”) (1958)

- Webpage with selection of Sonido 13 tracks

Want to read more?

- Sonido 13 is the subject of chapter 25 of my Mexican Kaleidoscope: myths, mysteries and mystique

- The website Indigenous Instruments of Mexico and Mesoamerica offers lots of interesting additional information about ancient musical instruments in Mexico.

Note:

[1] The bibliographic details for Andrea Teter’s article are currently unknown. Please contact us if you are able to supply any further information about these extracts, so that we can update to include the full reference.

Related posts: