There are now at least nine cable cars (teleféricos) for tourism operating in Mexico :

- Durango City, Durango

- Copper Canyon (Barrancas del Cobre), Chihuahua

- García Caves (Grutas de García), Nuevo León

- Zacatecas City, Zacatecas

- Hotel Montetaxco, Taxco, Guerrero

- Hotel Vida en el Lago, Tepecoacuilco, Guerrero

- Orizaba, Veracruz

- Puebla City, Puebla

- Torreón, Coahuila

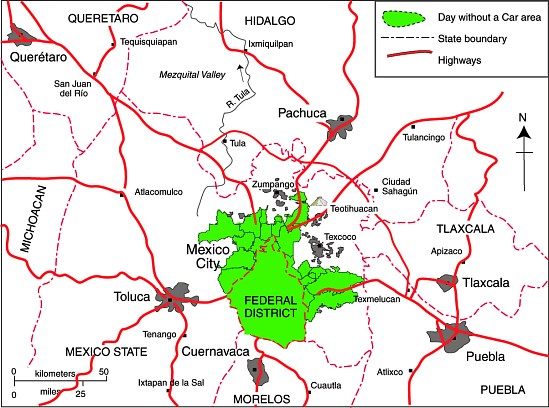

All these cable cars are primarily designed for sightseeing and tourism, rather than as a means of regular transport for local inhabitants. In addition, there is at least one urban cable car in the Mexico City Metropolitan Area designed for mass transit:

Durango City

The Durango teleférico, inaugurated in 2010, is 750 meters long. It links Cerro del Calvario in the historic center of the city with the viewpoint of Cerro de Los Remedios. It cost about $70 million to build and its two gondola cars can carry up to 5000 people a day. Parts of the ride are some 80 meters above the city. The system was built by a Swiss firm and is one of only a handful of cable cars that start from a historic city center anywhere in the world. (The Zacatecas City cable car is another).

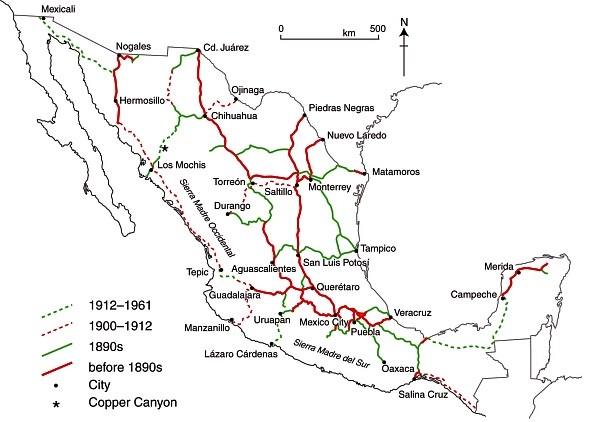

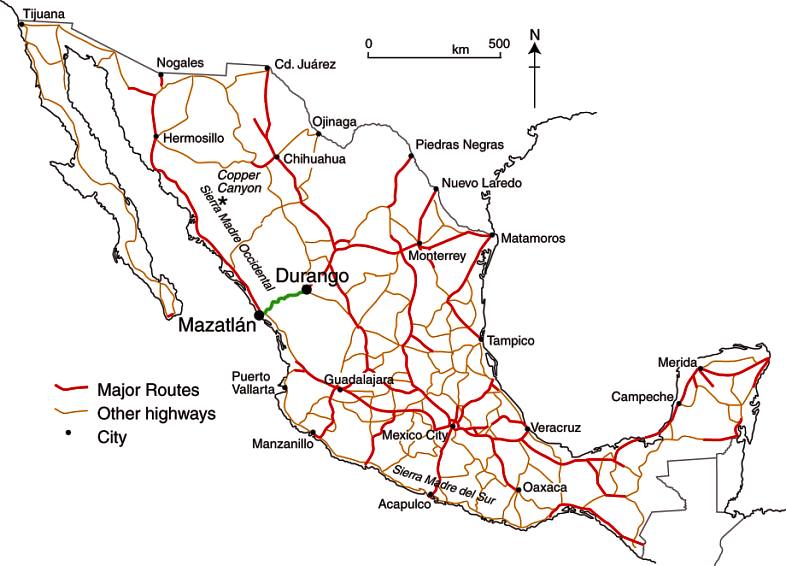

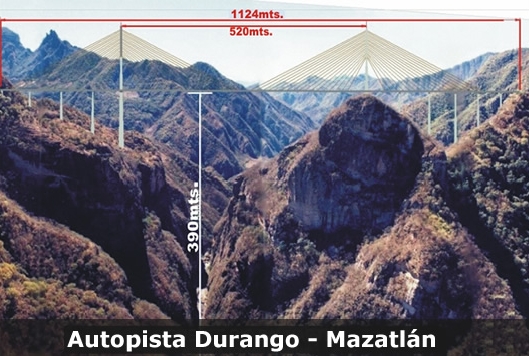

Copper Canyon (Barrancas del Cobre) in the state of Chihuahua

The Copper Canyon teleférico starts alongside Divisadero railway station in Mexico’s famous Copper Canyon region, and runs 2.8 km across a section of canyon, up to 400 meters above the ground level. Inaugurated in 2010, it is the longest cable car in Mexico, cost $25 million and can carry 500 passengers an hour, using two cabins (one traveling in each direction), each able to hold 60 people. It is a 10-minute ride each way to the Mesa de Bacajipare, a viewpoint which offers a magnificent view of several canyons.

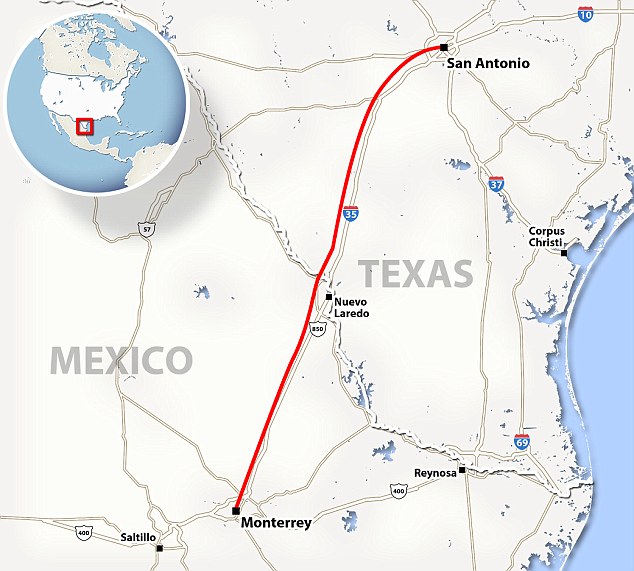

García Caves (Grutas de García) in Nuevo León

The Garcia Caves are located in the Cumbres de Monterrey National Park, 9 km from the small town of García, and about 30 km from the city of Monterrey. The caves are deep inside the imposing Cerro del Fraile, a mountain whose summit rises to an elevation of 1080 meters above sea level, more than 700 meters above the main access road. The entrance to the caves is usually accessed via a short ride on the 625-meter teleférico, which was built to replace a funicular railway.

Zacatecas City

The Zacatecas teleférico, opened in 1979, is 650 meters long and links the Cerro del Grillo, near the entrance to the El Eden mine on the edge of the city’s historic center, with the Cerro de la Bufa. It carries 300,000 people a year high over the city, affording splendid views of church domes, homes, narrow streets and plazas during a trip that lasts about ten minutes. On top of Cerro de la Bufa is an equestrian statue of General Doroteo Arango (aka “Pancho” Villa), commemorating 23 June 1914, when he and his troops successfully captured the city after a nine-hour battle.

La Bufa is also the setting for a curious children’s New Year legend involving a giant cave housing a great palace with silver floors, gold walls, and lights of precious stones. This palace is inhabited by thousands of gnomes, whose job is to look after the future “New Years”. Each December the gnomes choose which “New Year” will be given to the world outside… (For the full story, see chapter 21 of my Western Mexico, A Traveler’s Treasury)

Hotel Montetaxco, in Taxco, Guerrero

This hotel teleférico is a convenient link between the hotel, set high above the city, and the downtown area of this important tourist destination, best known for its silver workshops.

Hotel Vida en el Lago, in Tepecoacuilco, Guerrero

A second hotel in Guerrero also has its own teleférico, running from the hotel to a viewpoint atop the Cerro del Titicuilchi.

Orizaba, Veracruz

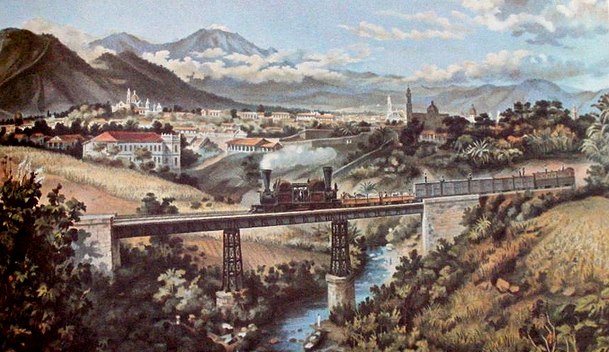

A 950-meter-long cable car, using 6-person cabins (see image), began operations in the city of Orizaba in Veracruz in December 2013. The cable car goes from Pichucalco Park, next to the City Hall in downtown Orizaba, to the summit of Cerro del Borrego. which overlooks the city. The 8-minute ride affords outstanding views over the city center.

Puebla City

Initial construction of the teleférico in the city of Puebla, in central Mexico, was halted in 2013, amidst considerable controversy about its route and the demolition of a protected, historic building (the Casona de Torno) in this UNESCO World Heritage city. The original route was 2 kilometers long and linked the historic center of Puebla with a nearby hill, home to the forts of Loreto and Guadalupe. In 1862, these forts were the site of the famous Battle of Puebla, at which Mexican forces proved victorious over the French, a victory celebrated each year on 5 May (Cinco de Mayo).

When it proved impossible to inaugurate this cable car in time for Mexico’s 2013 Tourist Tianguis (the largest tourism trade fair in Latin America), authorities boarded up the partially-completed structures (3 metal towers and 2 concrete bases) to completely hide them from public view. Construction resumed in 2014, but only of a 688-meter-long stretch which cost $11 million to build. This section, which includes a tower in Centro Expositor, the city’s main exhibition center, was officially opened in January 2016. The 5-minute ride costs about $30 pesos ($1.60) each way.

Torreón, Coahuila (opened December 2017)

Italian firm Leitner Ropeways constructed Torreón’s cable car. (Leitner built Mexico’s first cable car for regular urban transit in Ecatepec in the State of Mexico). The Torreón cable car runs 1400 meters between Paseo Morelos in the downtown area and the Cerro de las Noas, site of the large sculpture El Cristo de las Noas, reputedly the largest statue of Christ in North America.

The system will initially have nine 8-pasenger cabins giving a capacity of about 380 passengers an hour each way. The cable car cost between $9 million and $10 million. It was originally due to enter service in December 2016 but finally opened in December 2017. Users pay about 3 dollars for a round trip (about 5 minutes each way). City officials hope its completion will provide a welcome boost to Torreón’s fledgling tourism sector.

[Note: This is an updated version of a post first published in 2014]

Related posts:

- Passenger cable car for Mexico City (updated Jan 2016)

- Will Mexico City add cable cars to its mass transit system? (Apr 2013)