This account of the rope-making industry in the small village of Villa Progreso in the state of Querétaro, is based on information collected during numerous student interviews conducted in the village in the 1980s.

Villa Progreso in the 1980s

Villa Progreso is nestled in the hills at the end of a road, east of the town of Ezequiel Montes. The rocky soil is not very fertile, and water is in short supply, so agricultural production is limited, though maguey plants grow well here, even when neglected. The local maguey plants used to supply the raw material for rope-making, the main “secondary” occupation in the village.

However, as the village’s population increased, and as more and more families became dependent on rope-making, another maguey product, ixtle de henequen (henequen fibers), had to be trucked in as the raw material from other states, in particular from Yucatán and Tamaulipas.

The trucks are either rented by the villagers or supplied by the village “distributors” (who eventually buy the finished ropes from the village). About 40 metric tons of henequen are needed each week to keep the rope-makers supplied.

In the 1980s (all monetary figures are from that time), raw henequen was bought by the distributors for about 50 pesos a kilo, and then resold to the villagers at about 95 pesos a kilo. The distributors are “middle men” who, in the words of one student, “make a lot of money doing nothing” and “live in the largest, most expensive homes in the village.”

Once the villagers have purchased a supply of henequen, they perform the various tasks to turn it into ropes. The first step is to “comb” it to make fine fibers and to clean the henequen.

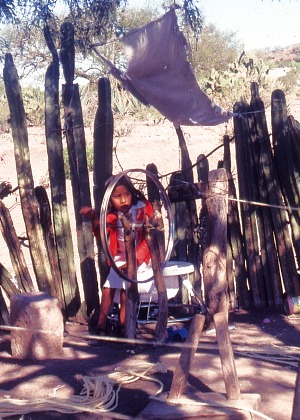

The fibers are then shaken in the wind to further separate them before being stored in a large sack. The ends of the top fibers are then tied onto three wires (see first photo). These wires are made to spin by a wheel.

This is often an old bicycle wheel. Some villagers turn the wheel themselves as they walk backwards feeding fibers onto the wires, via a rope that is wound over the wheel; others rely on children or family members to turn the wheel.

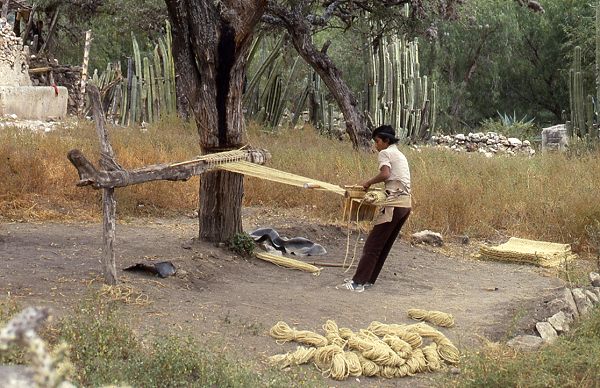

As the person carrying the sack walks backwards, they continue to feed the three strands of fiber, gradually creating three fine strands of rope. The spinning process is repeated, using the fine strands as the basis, and the rope can be made as thick as you like by successive spins.

The main output from this system is strands of rope of various thicknesses, used for things such as clothes lines. Short strands of henequen are not wasted, but formed into natural cleaning pads.

The work is done by the entire family. One worker pointed out that “it is better to have a large family as like this all can work for each other”. Any workers who have no family have to hire extra workers and are unlikely to make any profit.

On a good day, one family can produce about 72 ropes, each about 5 meters long, which can be sold for around 1800 pesos. However, it takes about 1 kilo of henequen to make 7 or 8 ropes, so the family only makes about 800 pesos [about 5 dollars at the then exchange rate] a day after they have paid for the “raw” henequen. The average family size, including children, in the village was between 5 and 6 individuals. 800 pesos a day is not much income to support the entire family!

The finished ropes are bought by the distributors, who in turn sell it on to other distributors in other places, and so on. The main markets are Mexico City, where about 90% of these ropes are eventually sold.

The workers in the rope-making industry in Villa Progreso have tried to organize themselves, but with only limited success. For example, three years before the interviews, they had formed a cooperative, but decided to quit the group when they realized that the managers of the cooperative also wanted part of the profits. So, at the time of the interviews, they had returned to working independently without any outside help.

Sales of rope fluctuate with the economy, and also seasonally, with the highest demand during the rainy season, partly because these natural fiber ropes tend to disintegrate more quickly during damp conditions.

As one student concluded, “It is very visible here how the middle men (distributors) take advantage of the cheap labor available and make a large profit by only buying and selling raw materials and by buying and selling finished products. thus, the distributors are getting richer by exploiting the workers and the workers are remaining as poor or getting poorer than before. The workers have been pulled into a situation that they can not easily escape from.”

How have things changed since the 1980s?

Sadly, I haven’t had the chance to return to Villa Progreso since then, but things appear to have changed considerably. Newspaper accounts such as “Artesanos dan nuevo aire al ixtle” (“Artisans give new life to Ixtle”), which appeared in the national daily El Universal in 2008, suggest that the residents of Villa Progreso are now emerging from some very hard times.

The price of natural fiber ropes could not compete with cheaper plastic alternatives and the rope-making industry went into near-terminal decline. Many of the able-bodied young men left to look for work north of the border. A small number (mainly the older inhabitants) remained home and continued to make ropes by hand for the limited market that remained for their products.

Now, though, a new industry has arisen based on the henequen fibers (usually known simply as ixtle). Enterprising villagers have turned their hands to fashioning nativity scenes and decorative items out of ixtle. Isaías Mendoza Guzmán is described in the article as making pieces that are more than two meters tall and take three months to complete, clearly indicating a high level of sophistication in the final product.

Villa Progreso now holds an Ixtle and Nopal Fair (Feria del Ixtle y el Nopal) towards the end of April each year in the La Canoa “ecotourism park”.

Villa Progreso is by no means the only place in Mexico where rope-making is an important activity. Similar rope-making methods are used elsewhere in Mexico. For example, John Pint describes in “Mexican artisans of Lake Cajititlán” how rodeo-quality lariats are made in the village of San Miguel Cuyutlán, near Guadalajara. Demand for these high-end products apparently remains strong.

Photo credit:

All photos in this post are by Tony Burton; all rights reserved.

How to get there:

Villa Progreso is about 10 km east of the town of Ezequiel Montes in Querétaro. From Mexico City, take the Querétaro highway (Hwy 57D) north-west to San Juan del Río. Then take Highway 120 past Tequisquiapan to Ezequiel Montes. Once in the town, turn right for the road to Villa Progreso. Allow 2.0 to 2.5 hours for the drive.

Related posts about the same general area:

- The geography of Tequisquiapan, a spa town in the state of Querétaro

- Rocks and relief fieldtrip: Tequisquiapan and the Peña de Bernal

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.