Celebrations for Mexico’s Day of the Dead (Día de Muertos) or, more correctly Night of the Dead (Noche de Muertos), date back to pre-Hispanic times. Indigenous Mexican peoples held many strong beliefs connected with death; for example that the dead needed the same things as the living, hence their bodies should be buried with their personal possessions, sandals and other objects.

With the arrival of the Spanish, the Indians’ pagan ideas and customs were gradually assimilated into the official Catholic calendar. Dead children (angelitos) are remembered on November 1st, All Saints’ Day, while deceased adults are honored on November 2nd, All Souls’ Day. On both days, most of the activity takes place in the local cemetery.

In many locations, festivities (processions, altars, concerts, meals, dancing, etc) now last several days, often beginning several days before the main days of November 1st and 2nd.

Day of the Dead: Top Nine Locations

The Day of the Dead was designated an “intangible world heritage” by UNESCO in 2008. The official UNESCO description of Mexico’s “Indigenous Festivity dedicated to the Dead” summarizes its significance:

“As practised by the indigenous communities of Mexico, el Día de los Muertos (Day of the Dead) commemorates the transitory return to Earth of deceased relatives and loved ones. The festivities take place each year at the end of October to the beginning of November. This period also marks the completion of the annual cycle of cultivation of maize, the country’s predominant food crop.”

“Families facilitate the return of the souls to Earth by laying flower petals, candles and offerings along the path leading from the cemetery to their homes. The deceased’s favorite dishes are prepared and placed around the home shrine and the tomb alongside flowers and typical handicrafts, such as paper cut-outs. Great care is taken with all aspects of the preparations, for it is believed that the dead are capable of bringing prosperity (e.g. an abundant maize harvest) or misfortune (e.g. illness, accidents, financial difficulties) upon their families depending on how satisfactorily the rituals are executed. The dead are divided into several categories according to cause of death, age, sex and, in some cases, profession. A specific day of worship, determined by these categories, is designated for each deceased person. This encounter between the living and the dead affirms the role of the individual within society and contributes to reinforcing the political and social status of Mexico’s indigenous communities.”

The Day of the Dead celebration holds great significance in the life of Mexico’s indigenous communities. The fusion of pre-Hispanic religious rites and Catholic feasts brings together two universes, one marked by indigenous belief systems, the other by worldviews introduced by the Europeans in the sixteenth century.”

Here, in no particular order, are 9 of the best places to visit for Mexico’s Day of the Dead:

1. Michoacán

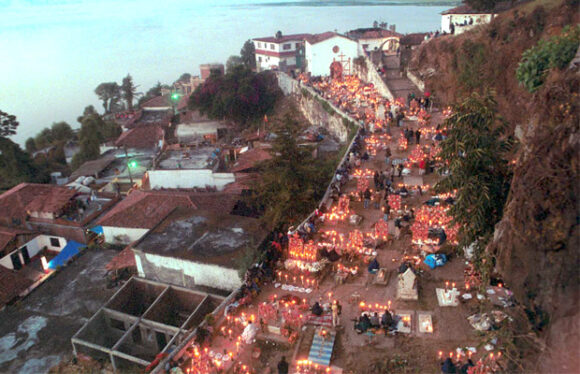

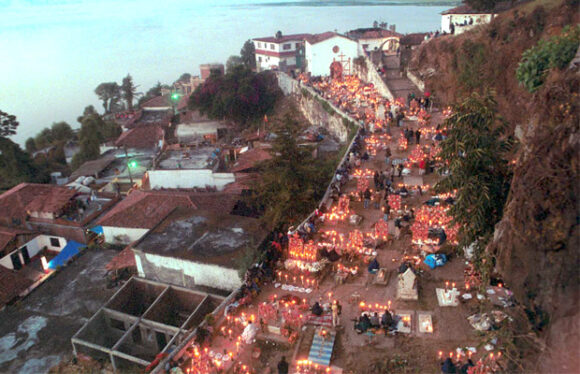

The single best-known location for Day of the Dead in the entire country is the Island of Janitzio in Lake Pátzcuaro, Michoacán. This is one of Mexico’s most famous major annual spectacles. Thousands of visitors from all over the world watch as the indigenous Purepecha people perform elaborate rituals in the local cemetery late into the night. Yes, it has become commercialized, but it remains a memorable experience, and also offers the opportunity to sample the local cuisine, which itself was declared an “intangible world heritage” by UNESCO in 2010!

Janitzio cemetery

Several other locations in the Lake Pátzcuaro area, including Ihuatzio, Tzintzuntzan, Arocutín and Jarácuaro, offer their own equally memorable (but less visited) festivities and rituals. Interesting observances of Day of the Dead also occur in many other places in Michoacán, including Angahuan (near Paricutin Volcano) and Cuanajo.

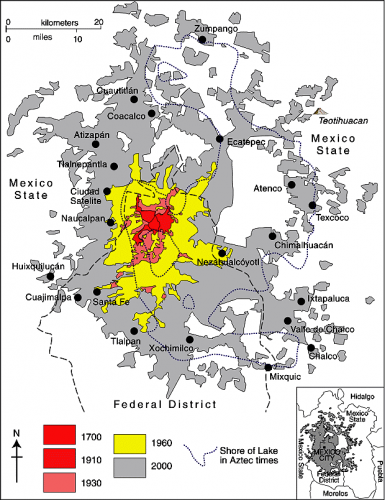

2. Mexico City

Two locations in the southern part of the city are well worth visiting for Day of the Dead.

In San Andrés Mixquic, which has strong indigenous roots, graves are decorated with Mexican marigolds in a cemetery lit by hundreds and hundreds of candles. Street stalls, household altars and processions attract thousands of capitalinos each year.

In Xochimilco, the canals and chinampas are the background for special night-time Day of the Dead excursions by boat (trajinera).

3. Morelos

Ocotepec, on the outskirts of Cuernavaca, is another excellent place to visit for Day of the Dead activities.

4. Veracruz

Xico, one of Mexico’s Magic Towns, has colorful Day of the Dead celebrations, including a flower petal carpet along the road to the graveyard. Don’t miss sampling the numerous kinds of tamales that are a mainstay of the local cuisine.

5. San Luis Potosí and Hidalgo

In the indigenous Huastec settlements of the mountainous area shared by the states of San Luis Potosí and Hidalgo, the celebrations for Day of the Dead are known as Xantolo. Multi-tiered altars are elaborately decorated as part of the festivities.

6. Chiapas

Several indigenous communities in Chiapas celebrate the Day of the Dead in style. For example, in San Juan Chamula, the festival is known as Kin Anima, and is based on the indigenous tzotzil tradition.

San Juan Chamula

7. Yucatán and Quintana Roo

In the Maya region, Day of the Dead celebrations are known as Hanal Pixan, “feast for the souls.” Families prepare elaborate food for the annual return of their dearly departed. The cemeteries in the Yucatán capital Mérida are well worth seeing, as are the graveyards in many smaller communities. See, for example, this account of the festivities in Pac Chen, Quintana Roo: Hanal Pixan, Maya Day of the Dead in Pac Chen, Quintana Roo

Tourist locations offer their own versions of Day of the Dead celebrations. For example, Xcaret theme park, in the Riviera Maya, is the scene of the Festival of Life and Death (Festival de la Vida y la Muerte) featuring parades, rituals, concerts, theater performances and dancing.

8. Oaxaca

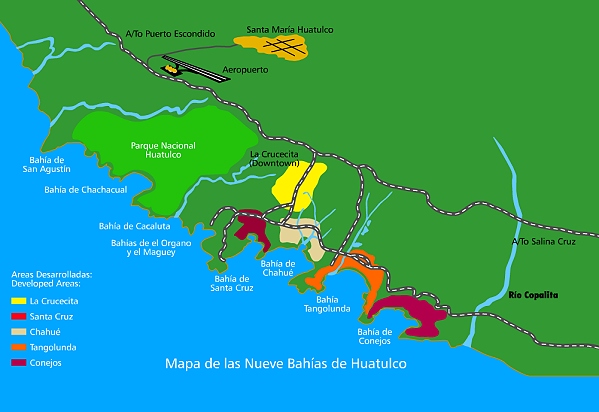

There are rich and varied observances of Day of the Dead in the state of Oaxaca. Visitors to Oaxaca City can witness vigils in several of the city’s cemeteries and night-time processions called comparsas. The celebrations are very different on the Oaxacan coast, as evidenced by this account of Day of the Dead in Santiago Pinotepa Nacional.

9. Guanajuato

The city of San Miguel de Allende in Guanajuato holds an annual four-day festival known as “La Calaca” with artistic and cultural events that are “integrated into the vibrant celebration of life and death known as Dia de Muertos”.

In Mexico, the age-old cultural traditions of Day of the Dead are still very much alive!

Note for armchair travelers

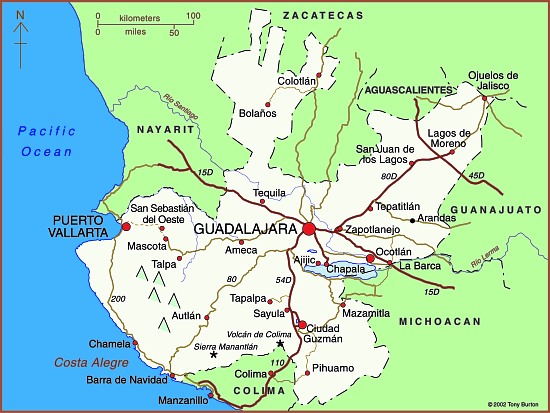

Besides the usual travel accounts describing Day of the Dead, there are numerous children’s and adult novels including vivid accounts of typical Day of the Dead activities. There are also various novels entitled Day of the Dead, though not all of them are focused on the Mexican tradition. One of the earliest of the novels entitled Day of the Dead is Bart Spicer’s 1955 spy novel, Day of the Dead, which has several scenes in Chapala, Guadalajara and Mexico City.

Related links: