Numerous academic studies have looked at different aspects of the long-established Ajijic retirement community at Lake Chapala. The earliest studies, in the 1970s, looked almost exclusively at the characteristics of the incoming migrants.

Mexican sociologist Francisco Talavera Salgado in Lago Chapala, turismo residencial y campesinado, focused exclusively on the varied impacts of foreign residents on the local Ajijic community.

Anthropologist Eleanore Moran Stokes homed in on Ajijic and suggested that the evolution of the village after ‘Discovery’ could be divided into three distinct phases: Founder (1940s to mid 1950s), Expansionary (mid 1950s to mid 1970s) and Established Colony (mid 1970s through the 1980s). During the Founder phase, Ajijic served, in her view, largely as an artists’ colony, whereas later (Expansionary phase) arrivals tended to be members of the affluent and retired middle class; these newer arrivals began to materially change the village by infusing cash into the local economy and starting businesses. They upgraded village homes and created “a new wage labor class in the village.”

Anthropologist Eleanore Moran Stokes homed in on Ajijic and suggested that the evolution of the village after ‘Discovery’ could be divided into three distinct phases: Founder (1940s to mid 1950s), Expansionary (mid 1950s to mid 1970s) and Established Colony (mid 1970s through the 1980s). During the Founder phase, Ajijic served, in her view, largely as an artists’ colony, whereas later (Expansionary phase) arrivals tended to be members of the affluent and retired middle class; these newer arrivals began to materially change the village by infusing cash into the local economy and starting businesses. They upgraded village homes and created “a new wage labor class in the village.”

In the Established Colony phase vacant houses became increasingly scarce, agricultural land was parceled for vacation and retirement homes, and philanthropic activities became important. Stokes estimated that, by 1979, foreigners occupied about 300 of the 950 houses in the village, but comprised less than 8% of the population.

Geographer David Truly built on Stokes’ framework to develop a matrix of retirement migration behavior. Like Stokes, Truly concluded in 2002 that newer visitors (including retirees), and unlike earlier migrants, had less desire to adapt to the local culture and were more keen on ‘importing a lifestyle’ to the area.

Sociologist Stephen Banks, studied the identity narratives of retirees while he was living in Ajijic in 2002-2003. He concluded that the responses he received during dozens of in-depth interviews revealed:

a struggle to conserve cultural identities in the face of a resistant host culture that has been colonized…. The Lakeside economy is dominated by expatriate consumer demand; indigenous commerce in fishing has disappeared as new employment opportunities opened up in the services sector; local prices for real estate (routinely listed in US dollars), restaurant dining, hotel lodging and most consumer goods are higher than in comparable non-retirement areas; traditional Mexican community life centered around the family has been supplemented, and in some cases supplanted, by expatriate community life centered around public assistance and volunteer programs… and the uniform use of Spanish in public life is displaced by the use of English.”

Some more recent work has focused on the changes in the host community. For example, Marisa Raditsch investigated the impacts of international migrants “based on the perceptions of Mexican people in the receiving context.” Her 2015 study found that these perceptions tended “to be favorable in terms of generating employment and contributing to the community; and unfavorable in terms of rising costs of living and some changes in local culture.”

Even more recently, Mexican researcher Mariana Ceja Bojorge focused squarely on the relationships and interactions between local Ajijitecos and foreigners. She concluded in 2021 that the shift “endangers the acceptance of the presence of the other” and that “Although the presence of foreigners has generated economic well-being in the area, it has also been responsible for the reconfiguration of space, where locals have been forced to leave their territory.”

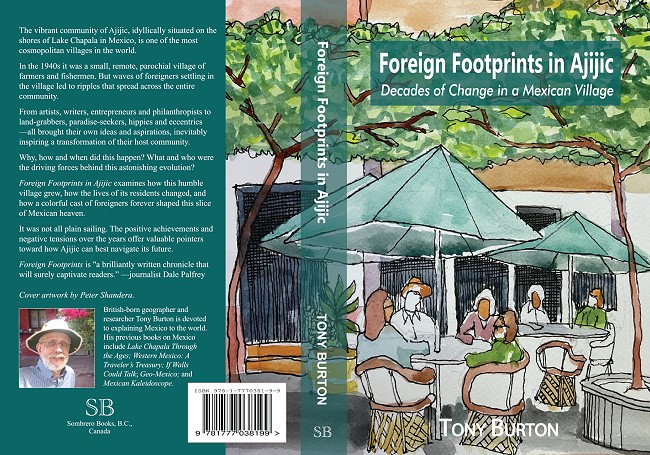

The details of the extraordinary changes that have taken place in Ajijic since the 1930s are the subject of my 2022 book, Foreign Footprints in Ajijic: Decades of Change in a Mexican Village.

This cover of the book shows a popular restaurant on Ajijic plaza, a perfect example of these changes or reconfiguration of space. The plaza was originally a Mexican space, where locals filled water containers, met friends, gossiped, socialized and bargained at the weekly market. The chapel and all the stores around the plaza were exclusively run by village residents to meet local needs. In those years, if there was a center for foreigners it was the Posada Ajijic bar, restaurant and gardens.

The use of the plaza has changed. After Cine Ajijic opened on the north side of the plaza in 1969, its weekly English-language films actively encouraged foreigners (en masse) to share the same social space as the local community. The supermarket on the south side of the plaza also became a shared space for locals and foreigners, a dual role which continued after the premises became a bank. Stores and restaurants either owned by, or designed to serve, foreigners were established around the plaza. An even stronger foreign focus is evident in the plaza coffee shops which spill over onto what was formerly public space. This has inevitably resulted in a debate about the appropriateness of a private enterprise occupying public space, and whether even paid use, via concessions, is an acceptable tradeoff for the loss of such space. Compromise is needed by all; there will never be any one-size-fits-all solution to any of the issues arising from migration and cultural change.

Full bibliographic details of all the studies mentioned above are included in the bibliography of Foreign Footprints in Ajijic: Decades of Change in a Mexican Village

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.