In recent years, considerable attention has focused on the US government’s efforts to stem the flow of Mexicans migrating north of the border in search of jobs. But there was a time in history when the boot was, so to speak, very much on the other foot.

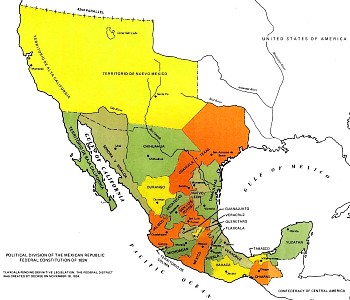

In the early 19th century, shortly after gaining her Independence from Spain (1821), Mexico’s territory extended considerably further north than it does today. It included modern-day Texas, as well as many other parts of what later became US territory.

The first British Chargé d’Affaires in Mexico was Sir Henry George Ward (1797-1860). Ward entered the diplomatic service in 1816, and first visited Mexico in 1823, as a member of a British government commission assessing the desirability of establishing trading relations following Independence. The following year, he married Emily Elizabeth Swinburne, who accompanied him on his return to Mexico in 1825 in his role as Chargé d’Affaires.

Two years later, Ward wrote a detailed description of how he saw Mexico. Mexico in 1827, which contains illustrations by his wife, was an early appraisal of the fledgling Mexican Republic, and was published on his return to the UK. Ward’s book provides numerous details of trade, mining, economic activity and topography, as well as pointing out many errors in Alexander von Humboldt’s earlier classic work Political Essay on the Kingdom of New Spain (1811).

Ward, a skilled diplomat, arrived only a few months before his American counterpart Joel Poinsett. (Poinsett, after whom the poinsettia is named, was the first US minister to Mexico). Ward was not only anti-Spanish, but also decidedly anti-American. His main goal, apparently, was to try to prevent the USA from expanding its territory at the expense of Mexico. The British diplomat believed that the incorporation of Texas into the Anglo-American states was inevitable unless the Mexican government could stem the wave of immigrants flooding southwards into the region. (How times have changed!)

The Mexican government was relatively unstable at this time, with frequent changes of leaders and some inconsistency in policies. Ward summed up the political situation that he encountered as one in which, after 13 years of civil war, the form of government had still not been determined, with great differences of opinion existing with respect to the desired degree of central authority. He found it difficult to conceive of any country less prepared than Mexico for the “transition from despotism to democracy”.

While both men were acting on behalf of their respective countries, Ward acted as a moderate balance to the interventionist politics of Poinsett. He promoted the signing of a UK-Mexico treaty of friendship, trade and migration, but the UK gradually lost influence in Mexico despite Ward’s best efforts. Meanwhile, Poinsett was trying his hardest to purchase Texas. His meddling in Mexican politics antagonized the government of Vicente Guerrero to the point where his recall was demanded in 1829.

The British Chargé d’Affaire’s greatest concern was that the USA might one day gain control over Texas ports. This would put them only three days away by boat from Tampico and Veracruz (Mexico’s main trading port) and mean that Mexico was vulnerable to invasion. Ward’s worst fears in this regard were realized later in the nineteenth century (the Mexican-American War of 1846-1848).

Original article on MexConnect.

The changing political boundaries of Mexico are described in chapter 12 of Geo-Mexico: the geography and dynamics of modern Mexico. Buy your copy today!