Mexico’s 2010 population of 112 million makes it the world’s 11th largest country in terms of population. The rate of population increase is now slowing down as fertility rates fall. The rate of increase, which was 2.63%/yr for the period 1970-1990, fell to 1.61%/yr for the period 1990-2010.

Even as the total population continues to grow over the next few decades, some very important changes are underway in Mexico’s population structure.

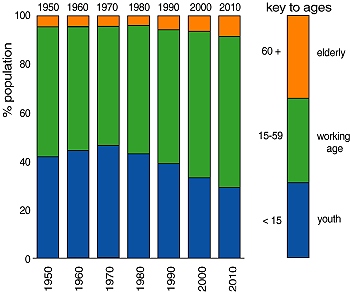

The graph divides Mexico’s population into three age categories: under 15 (youth), 15-59 (working age) and 60+ (elderly).

The percentage of the total population of youthful age peaked in about 1970 at 46.2% and has since fallen to 29.3% in 2010. Over the same time period, the percentage of working age population has risen from 48.2% to 61.6%, while the percentage of elderly has gone from 5.6% to 9.1%.

Why is this important?

Perhaps the most obvious change is that government spending on schools and services for youth needs to shift towards spending on health care, pensions and services for the elderly. There are already some suburbs of the Mexico City Metropolitan Area that have experienced a dramatic shift in average age. Perhaps the most notable example is the Ciudad Satelite area, an area originally intended to be, and planned as, a genuine satellite settlement. A few decades later, the urban expansion of Mexico City had swallowed it up. An area which once had many young families now has very few children. The homeowners association of Ciudad Satelite estimates that 75% of the area’s 50,000 inhabitants is now elderly.

The major benefit of the changing population structure would appear to be that, in 2010, there are more wage-earners (and tax payers) for every person of non-working age (assumed for simplicity to be youth under 15, and the elderly aged 60+) than at any previous time. In other words, the total dependency rate is lower than ever before.

Economists argue that this “demographic dividend” should raise GDP, and could offer many significant advantages, such as enabling greater government expenditures on infrastructure or on social services. They point to several countries in East Asia as examples where economic growth spurts went hand-in-hand with a period of demographic dividend.

Despite the claims of economists, I’m not convinced that Mexico will prove to be an equally good example of the benefits of a demographic dividend. In Mexico’s case, the early phase of higher youthful population (and considerable economic growth) was accompanied by a high rate of emigration of working age Mexicans to the USA. Admittedly, emigration has now slowed, or stopped.

As Aaron Terrazas and his co-authors point out in Evolving Demographic and Human-Capital Trends in Mexico and Central America and Their Implications for Regional Migration [pdf file],

“But across Latin America, and in sharp contrast to East Asia, favorable demographic change has failed to translate into economic growth and prosperity. National income per capita has increased only modestly since the start of the demographic dividend, with Mexico outperforming its southern neighbors at comparable points in time. And emigration from the region has continued to grow despite the demographic transitions in Mexico and El Salvador, with the United States absorbing between one-fifth and one-quarter of the region’s annual population growth.”

Whether or not Mexico experiences a demographic dividend, it will not last for ever. In Mexico’s case, it looks set to last only about about 20 years. By 2050, according to current predictions, about 26.4% of the Mexico’s population will be youthful, and 27.7% elderly, while the percentage of working age will have fallen to 45.9%.

Related posts:

- Mexico’s population is aging fast

- Mexico’s population pyramid (age-sex diagram) for 2010

- Mexico’s population keeps growing, but at a slower pace

- The average size of households in Mexico in 2010

- Map of population change in Mexico, 2000-2010

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.