Mexico has a long history of honey (miel) production. Honey was important in Maya culture, a fact reflected in some place names found in the Yucatán Peninsula, such as Cobá (“place of the bees”).

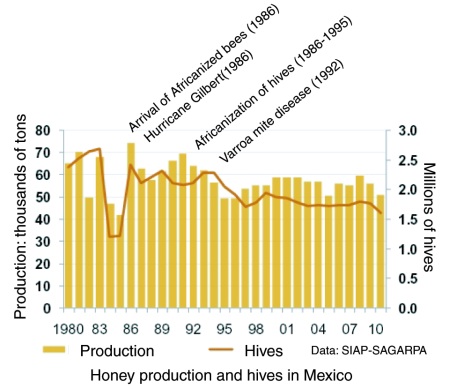

Faced by the arrival of Africanized bees – The diffusion of the Africanized honey bee in North America – Mexico’s modern commercial beekeepers initially feared the worst. With time, they became less antagonistic to Africanized bees, since, whatever their faults, they proved to be good honey producers.

Honey production has been on the rise in the past decade. Over the past five years, Mexican hives have yielded about 57,000 tons of honey a year, making Mexico the world’s sixth largest honey producing country. Preliminary figures for 2015 show that Mexico produced 61,881 tons of honey.

Mexico is also the world’s third leading exporter of honey with total exports (both conventional and organic honey) of 45,000 tons in 2015, a new record, worth over US$150 million. Mexico’s principal export markets for honey are Germany, the USA, the U.K. Saudia Arabia and Belgium.

Other major exporters of honey include China, Argentina, New Zealand and Germany.

There are 42,000 beekeepers nationwide, operating 1.9 million hives; the main producing area remains the southeast, especially the states of Campeche, Yucatán and Quintana Roo. Jalisco, Chiapas, Veracruz, Oaxaca, Guerrero, Puebla and Michoacán are also important for honey production.

The domestic consumption of honey in Mexico has risen from under 200 grams per person in the 1990s to more than 300 grams in 2010. This is mainly due to the use of honey in processed foods such as cereals, yogurts and pastries.

The major value of bees in an ecosystem is not for their honey production, but on account of their vital role in the pollination of trees and food crops, a contribution valued in the US alone at more than 10 billion dollars.

The major value of bees in an ecosystem is not for their honey production, but on account of their vital role in the pollination of trees and food crops, a contribution valued in the US alone at more than 10 billion dollars.

Views about the pollinating ability of Africanized bees, compared to European or native bees, are mixed. Some farmers dislike having to cope with potentially aggressive bees. Others claim that Africanized bees are far more efficient pollinators than European bees since they forage more often and at greater distances than their European counterparts. The available evidence does not appear to suggest that the arrival of Africanized bees had any impact on crop yields in Mexico.

Which Mexican honey should you buy? For a cautionary tale about choosing the best Mexican honey in overseas stores, see Honey, what’s on that label?

Sources:

- (a) La producción apícola en México by Carlos Angeles Toriz and Ana María Román de Carlos. (date unknown)

- (b) “Mexico ranks sixth in honey production” (reprinted from El Economista on mexicanbusinessweek.com), 2011.

This post was first written in October 2011, with updates in October 2015 and January 2016.