This post looks at where branches of Banamex (Banco Nacional de México) were founded in the period prior to 1960. Banamex is one of the oldest banking institutions in Mexico. It is now a subsidiary of Citigroup, but remains the second largest bank in the country after BBVA Bancomer.

Banamex was formed on 2 June 1884 from the merger of Banco Nacional Mexicano and Banco Mercantil Mexicano, two banks that had only been operating for a couple of years. Shortly after its founding, Banamex had branches in Mexico City, Mérida, Veracruz, Puebla, Guanajuato, San Luis Potosí, and Guadalajara.

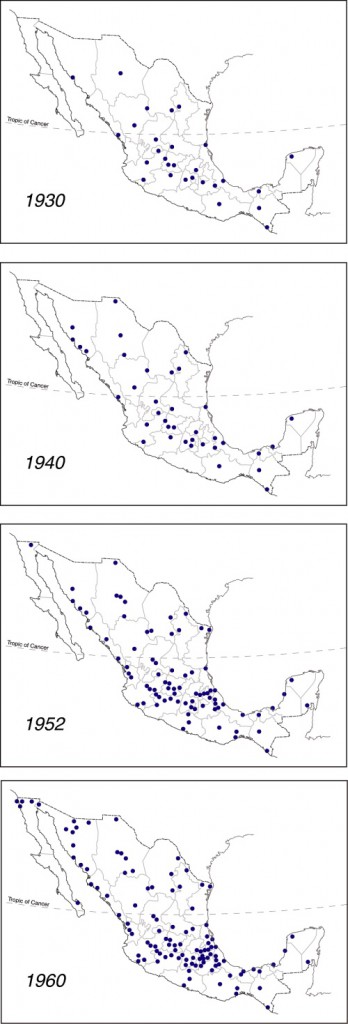

The maps to the left are based on Figure 8 of Las Regiones Geográficas en México by Claude Bataillon (8th edition, 1986, Siglo Veintiuno Editores).

Each dot represents the location of a branch of Banamex in the year shown. For simplicity’s sake, it is assumed that all branches present on any earlier map continued to exist through to 1960, and did not close or relocate in the interim.

The concept of spatial diffusion looks at the spread of an innovation, whether a new idea, technique, good, service or brand. The spatial diffusion of information or of the adoption of innovations is an important subset of spatial interactions. Looking at the spatial diffusion of a banking network offers lots of interesting insights into how Mexico’s economic geography has changed over the years.

There are three basic types of diffusion. The first is relocation diffusion where people travel or migrate and bring their cultural and technological practices with them. For example, modern studies in the genetics of corn (maize) have established that ancient Mexicans first domesticated corn in the Balsas valley. They then migrated both northwards and southwards, taking the practice of cultivating corn with them.

The second is contagious diffusion, which generally spreads from person to person and exhibits strong distance decay. An example is the spread of the Jehovah’s Witness faith in Mexico which required a considerable amount of face-to-face personal interaction. Many diseases also spread by contagious diffusion.

The third is hierarchical diffusion, which spreads across higher levels of a hierarchy and then down to lower levels. This is often how information from the top of an organization reaches those at the bottom. An example is the government’s 1970s family planning program that was first adopted in large cities, then smaller cities, and eventually penetrated into rural areas.

Combinations of these three types are also possible. One relatively recent example is the spread of the H1N1 influenza virus in early 2009. First reports were that it started in a rural village, probably in Oaxaca, and spread by contagious diffusion to others in the village. From there an infected person temporarily relocated to Mexico City where the flu again spread by contagious diffusion. From Mexico City, the top of the Mexican hierarchy, it spread down the hierarchy as carriers of the virus traveled to smaller Mexican cities and to other cities worldwide.

In the case of the diffusion of Banamex branches shown on the maps, the main type of diffusion involved is hierarchical. In this case, given that Banamex is a banking institution, the hierarchy reflects where most economic activity is taking place at the time. (There would be little point in placing a new branch in a location where little money was in circulation).

The 1930 distribution of Banamex branches looks to be quite scattered across the country, though Baja California and north-west Mexico have no branches and fall outside the network. By 1940 more additional branches have opened in the northern half of Mexico than the southern half, and the north-south economic divide that we have commented on in many previous posts is beginning to become apparent. Between 1940 and 1952 many new Banamex branches are added in central Mexico (this is the period when in-migration was turning Mexico City into a monster) and along the west coast, following the line of Highway 15 which runs from Guadalajara to the border with California. Overall, the north-south divide is now quite clear.

Between 1952 and 1960 additional branches open close to the US border, a branch finally reaches Baja California Sur (in La Paz) and the economic dominance of northern Mexico over southern Mexico is clearly established.

One of the most striking features, when comparing all four maps, is how the number of Banamex branches in southern and south-eastern Mexico (defined as the states of Chiapas, Tabasco, Campeche, Yucatán and Quintana Roo) barely changed between 1930 and 1960.

It would be interesting to update this example with similar maps for more recent years. Please contact us if you have access to suitable data or know where such data may be found.

Other posts related to the concept of diffusion:

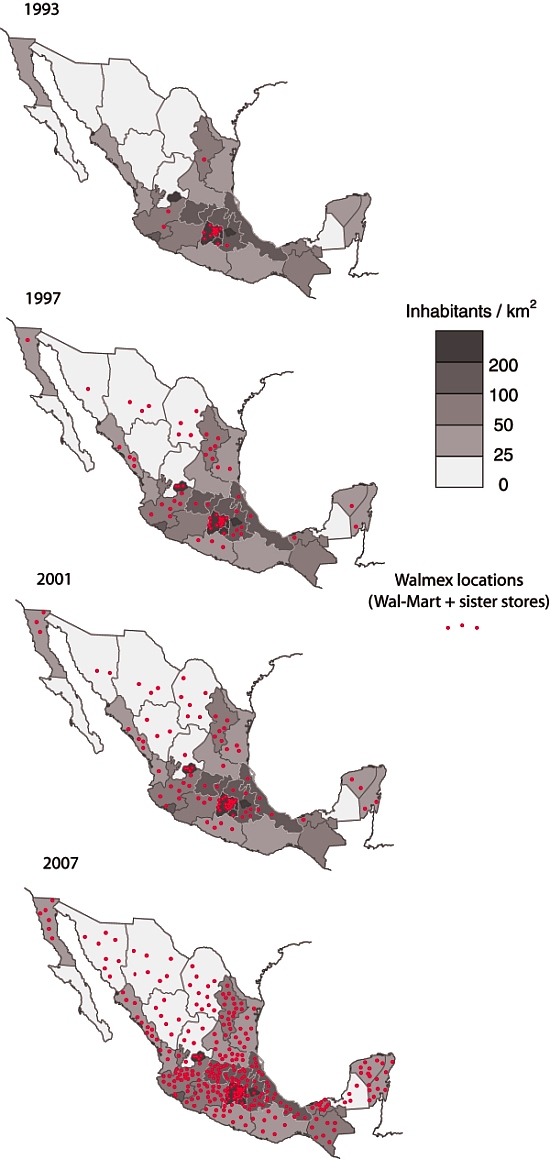

- The growth and expansion of Wal-Mart in Mexico

- The diffusion of the Africanized honey bee in North America: a bio-geographical case study

- Cultural diffusion: Thousands of students in Mexico receive classes by TV

- The diffusion of violence in Mexico since the early 1980s

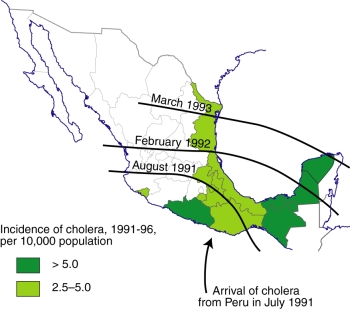

Another instance of diffusion, of cholera in Mexico during the 1991-1996 epidemic, is mapped and discussed in chapter 18 of Geo-Mexico: the geography and dynamics of modern Mexico. Geo-Mexico also includes an analysis of the pattern of HIV-AIDS in Mexico, and of the significance of diabetes in Mexico.