In a recent post, we looked at an Enchanted Lake in southern Mexico, in the Sierra de las Tuxtlas, near Catemaco in the Gulf Coast state of Veracruz. In this post we take a look at the surrounding Las Tuxtlas Biosphere Reserve.

Scenically, the entire Tuxtlas region is one of the most fabulously beautiful in all of Mexico. High temperatures combined with lots of rainfall result in luxuriant vegetation and boundless wildlife. Average monthly temperatures range from a pleasant 21 degrees C (70 degrees F) in January to a high of 28 degrees C (82 degrees F) in May, just before the rainy season kicks in. During the rainy season, from June to October, some 2000 mm (79 inches) of rain falls, often in late afternoon tropical deluges.

The jungle masking the lower slopes of the San Martín volcano gradually merges into tropical cloud forest at higher altitudes. Competing with the Silk Cotton (Kapok) and Ficus trees for light and sustenance are ground-hugging ferns. Overhead, the tangle of tree branches provides support for thousands of non-parasitic bromeliads (“air” plants) and orchids. More than 1300 species of flowering plants have been identified in this classic area for Neotropical ecology.

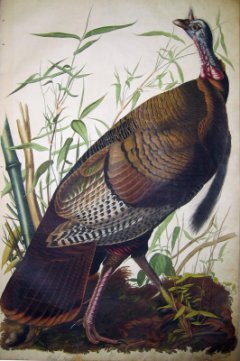

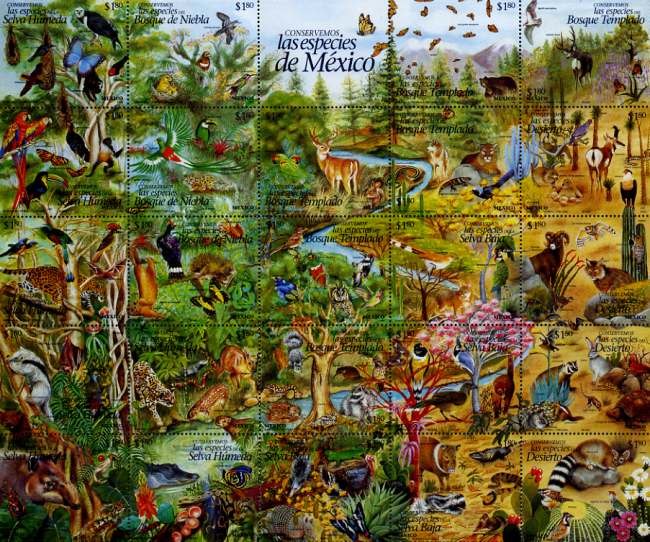

Bird-watchers are likely to spot the spectacular Keel-billed Toucan, or hear a Tody Motmot. Smaller birds include several species of hummingbird; look for the endemic Long-tailed Sabrewing. About half of all the bird species recorded in Mexico have been seen here, but birds are not the only wild animals inhabiting the jungle. Ocelots and tapirs are regularly seen and you may be lucky enough to see spider monkeys playing overhead in the canopy.

Clearance of the land for grazing and cultivation of the slopes to grow tobacco, bananas and sugar cane have reduced the original jungle to a relatively small number of isolated fragments. Fortuitously, this provides more varied habitats than the original vegetation, helping to enrich the area’s wildlife, further enhancing the region’s reputation as an ornithological and botanical paradise.

Fortunately an extensive area of this region was declared a Biosphere Reserve in 1998, ensuring that conservation programs now go hand-in-hand with human activities. The total area forming the Reserva de la Biósfera “Los Tuxtlas” is 155,122 hectares (380,000 acres).

Chapter 5 of Geo-Mexico: the geography and dynamics of modern Mexico focuses on Mexico’s ecosystems and biodiversity. Chapter 30 analyzes environmental issues and trends including current environmental threats and efforts to protect the environment. Buy your copy today to have a handy reference guide to all major aspects of Mexico’s geography!