El Pico de Orizaba, or Citlaltépetl (= “star”), is Mexico’s highest peak, rising to a summit 5,610 meters (18,406 feet) above sea level. The third highest peak in North America, it is also that region’s highest volcano, responsible for major eruptions in 1569, 1613 and 1687. The mountain was first explored by scientists as long ago as 1838.

Located east of Mexico City, some 30 kilometers (20 miles) northwest of the city of Orizaba, it is regularly climbed today by well-equipped groups, especially during the dry season, from December to April. Its classical cone shape masks an impressively large crater, which is more than 300 meters (1,000 feet) deep. The volcano and surrounding area were declared a national park by President Lázaro Cárdenas in 1936; the decree took effect the following January.

Among the first recorded ascents is that in August 1838 by a group of several European botanists: Henri Galeotti, Nicolas Funck, Auguste Ghiesbreght and Jean-Jules Linden. The group spent eleven days on the volcano and their subsequent accounts of the expedition show that they definitely reached the summit. Afterwards, they went on to have distinguished careers in their specialist fields.

By the time of the climb, Henri Guillaume Galeotti (1814-1858) had already written a landmark article about Lake Chapala, and made numerous botanical discoveries in Mexico. He went on to become Director of the Royal Botanical Gardens in Brussels, Belgium.

Less is known about the achievements of Nicolas Funck (1816-1896), who continued traveling in Mexico until 1842. He subsequently became director of Brussels Zoo (1861) and then Cologne Zoo.

After the climb, Auguste Ghiesbreght (1810-1893) set up his own business in Mexico, making a living by supplying plants and natural history specimens to European collectors and his botanist business partners. Who knows? Perhaps the plans for a cacti-exporting business (Galeotti) and large-scale orchid cultivation (Linden) were hatched while the group of young friends were battling their way towards the peak of Orizaba.

Jean Jules Linden (1817-1898), born in Luxembourg, collected for the Belgian government in Brazil, Mexico and Guatemala, before becoming one of the world’s most celebrated importers of plants. He set up nurseries for exotic plants in Brussels and Ghent in Belgium, as well as on the French Mediterranean coast. He also directed Brussels Zoo. He is credited with introducing and popularizing numerous plants, including begonias, palm trees and orchids. His superb publications on orchids and his marketing skills won him world-wide respect.

The nineteenth century craze for orchids in Belgium had numerous parallels with the craze three hundred years earlier for tulips in the Netherlands. The nouveau-riche industrialists satisfied their passion for expensive and unusual orchids by buying them from Linden who was propagating and growing them in massive, industrial-scale glasshouses. Even the Russian czar bought orchids from Linden!

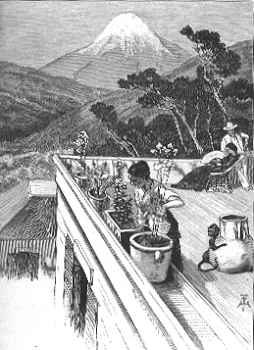

The explorations of Galeotti and his friends resulted in the volcano becoming much better known. A decade later, Carl Sartorius, an artist of German extraction who collected plants for the Berlin Botanical Gardens, and who owned the El Mirador hacienda close to the volcano, organized an expedition to reach the summit. When they reached the top, they found a simple plaque there already, left by two US soldiers, F. Maynard and G. Reynolds, who had served as troopers in Winfield Scott’s army during the 1846-1848 Mexican-American war.

Not surprisingly, the upper reaches of El Pico de Orizaba (above about 4,000 meters) are snow-capped all year. Though someone had probably skied down the mountain previously, the first recorded descent on skis was made by W. Furlinger in 1974. Schemes to open a skiing resort on its slopes have been suggested several times. Before any budding entrepreneurs get carried away with the possibilities, it should be pointed out that setting up permanent ski runs on the slopes of El Citlaltépetl may not be too smart an idea, given the likely impact of global warming.

This is an edited and updated version of an article originally published on MexConnect.

Acknowledgment

My thanks to Dr. Winston Crausaz. the author of Pico de Orizaba or Citlaltepetl (Geopress International, 1993), whose valuable comment on the original post (see below) has now been incorporated into the updated version above.

Mexico’s volcanoes, mountains and relief features are examined in chapters 2 and 3 of Geo-Mexico: the geography and dynamics of modern Mexico.