Retirees, mainly from the USA and Canada, form a special subgroup of tourists. About 1 million US visitors to Mexico each year are over the age of 60. Their total expenditure is about $500 million a year. Three-quarters arrive by air; half of these stay 4-8 days and almost one in ten stays 30 days or longer. Half stay in hotels, and one-third in time-shares; the remainder either stay with family or friends, or own their own second home. Of the 25% arriving by land, almost one in three stays 30 days or more. For Canadians, the patterns are broadly similar except that a higher percentage arrive by air.

The number of retiree tourists is relatively easy to quantify. However, it is extremely difficult to place accurate figures on the number of non-working, non-Mexicans who have chosen to relocate full-time to Mexico. Technically, these “residential tourists” are not really tourists at all but longer-term migrants holding residency visas. They form a very distinct group in several Mexican towns and cities, with lifestyle needs and spending patterns that are very different from those of tourists. Their additional economic impact is believed to exceed $500 million a year.

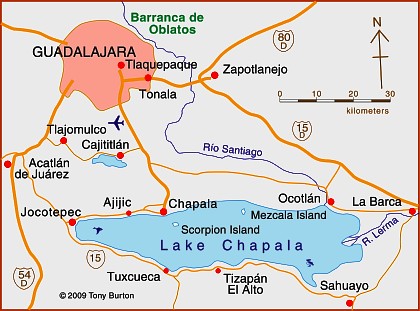

The largest single US retirement community outside the USA is the Guadalajara-Chapala region in Jalisco, according to state officials (see map). The metropolitan area of Guadalajara, Mexico’s second city, has a population of about 4 million. The villages of Chapala and Ajijic (combined population about 40,000) sit on the north shore of Lake Chapala some 50 km (30 mi) to the south. Historically, Chapala was the first lakeshore settlement to attract foreign settlers, as early as the start of the 20th century. Today the area is home to a mix of foreign artists, intellectuals, escapees (of various non-judicial kinds), pensioners and ex-servicemen. In the last 40 years, Ajijic has become the focal point of the sizable non-Mexican community living on the lakeshore. Depending on how they are defined, there are probably between 6000 and 10,000 foreign residents in the Chapala-Ajijic area, the higher number reflecting the peak winter season. About 60% of retirees in the area own their own homes or condos, though many still own property in the USA or Canada as well, and many make regular trips north of the border.

The main pull factors for residential tourists are an amenable climate; reasonable property prices; access to stores, restaurants and high quality medical service; an attractive natural environment; a diversity of social activities; proximity to airports; tax advantages, and relatively inexpensive living costs.

David Truly has suggested that conventional tourist typologies do not work well with Ajijic retirees. He identified migrant clusters with similar likes and dislikes. Retirees vary in education, travel experience and how they make decisions about relocation. Early migrants tended to dislike the USA and Canada and adapted to life in Mexico. They were generally content with anonymity unlike many more recent migrants. Traditional migrants appreciate all three countries, but have chosen Mexico as their place of permanent residence. Many new migrants do not especially like the USA or Canada but are not particularly interested in Mexico either. They seek familiar pastimes and social settings and are content to have relatively little interaction with Mexicans.

The large influx of residential tourists into small lakeside communities like Ajijic inevitably generates a range of reactions among the local populace. From empirical studies of regular tourism elsewhere, George Doxey developed an “irritation index” describing how the attitudes of host communities change as tourist numbers increase. His model applies equally well to residential tourists. In the initial stage the host community experiences euphoria (all visitors are welcome, no special planning occurs). As numbers increase, host attitudes change to apathy (visitors are taken for granted) and then annoyance (misgivings about tourism are expressed, carrying capacities are exceeded, additional infrastructure is planned). If numbers continue to grow, hosts may reach the stage of antagonism, where irritations are openly expressed and incomers are perceived as the cause of significant problems.

Residential tourism in the Chapala-Ajijic area has certainly wrought great changes on the landscape. Residential tourists have created a distinct cultural landscape in terms of architectural styles, street architecture and the functions of settlements. (Browse the Chapala Multiple Listing Service New Properties). Gated communities have been tacked on to the original villages. Subdivisions, two around golf courses, have sprawled up the hillsides. Swimming pools are common. Much of the signage is in English. Even the central plazas have been remodeled to reflect foreign tastes. Traditional village homes have been gentrified, some in an alien “New Mexico” style.

On the plus side, many retirees, as a substitute for the family they left behind, engage in philanthropic activities, with a particular focus on children and the elderly. Retiree expenditures also boost the local economy. Areas benefiting from retirees include medical, legal and personal services, real estate, supermarkets, restaurants, gardening and housecleaning. Employment is boosted, both directly and indirectly, which improves average local living standards.

On the minus side, decades of land speculation have had a dramatic impact on local society. Land and property prices have risen dramatically. Many local people have become landless domestic servants, gardeners and shop-keepers with a sense that the area is no longer theirs. Crime levels have risen and some local traditions have suffered. The abuse of water supplies has resulted in declining well levels. Over zealous applications of fertilizers and pesticides have contaminated local water sources.

Other locations besides Chapala-Ajijic where a similar influence of non-Mexican retirees on the landscape can be observed include San Miguel de Allende (Guanajuato), Cuernavaca (Morelos), Mazatlán (Sinaloa), Puerto Peñasco (Sonara), Rosarito (Baja California) and Todos Santos (Baja California Sur). The most preferred locations are all on the Pacific coast side of Mexico.

As more baby-boomers reach retirement age, residential tourism offers many Mexican towns and cities a way of overcoming the seasonality of conventional tourism. Lesser-developed regions have an opportunity to cash in on their cultural and natural heritage and improve their basic infrastructure.

This is a lightly edited excerpt from chapter 19 of Geo-Mexico: the geography and dynamics of modern Mexico.

References:

- Boehm S., B. 2001 El Lago de Chapala: su Ribera Norte. Un ensayo de lectura del paisaje cultural. 2001. Relaciones 85, Invierno, 2001. Vol XXII: 58-83.

- Burton, T. 2008 Lake Chapala Through the Ages, an Anthology of Travellers’ Tales. Canada: Sombrero Books.

- Doxey G.V. 1975 A causation theory of visitor‑resident irritants: methodology and research inferences. Proceedings of the Travel Research Association, San Diego, California, USA: 195‑8.

- Stokes, E.M. 1981 La Colonia Extranero: An American retirement Community in Ajijic, Mexico. PhD dissertation, University of New York, Stony Brook, cited in Truly, D. 2002.

- Truly, D. 2002 International Retirement migration and tourism along the Lake Chapala Riviera: developing a matrix of retirement migration behavior. Tourism Geographies. Vol 4 # 3, 2002: 261-281.

- Truly, D. 2006 The Lake Chapala Riviera: The evolution of a not so American foreign community, in Bloom, N.D. (ed) 2006 Adventures into Mexico: American Tourism beyond the Border. Rowman & Littlefield: 167-190

Related posts:

- Map of the state of Jalisco, including Guadalajara and Chapala

- How big is Lake Chapala?

- How Lake Chapala, Mexico’s largest lake, was formed

- The sacred geography of Mexico’s Huichol Indians

- Population change in Jalisco, 2000-2010

- Population change in the Guadalajara Metropolitan Area

- Giant whirlpool swallows several boats in 1896

- Where in Mexico will U.S. baby-boomers choose to live?

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.