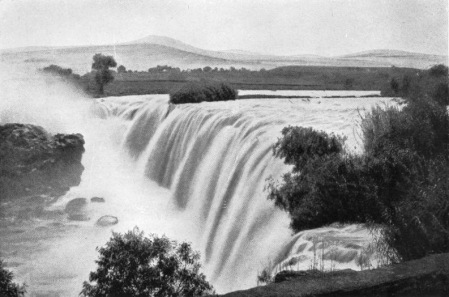

Geo-Mexico has repeatedly lamented the sad state of the Juanacatlán Falls, the “Niagara of Mexico”, near Guadalajara. More than a century ago, they were considered a national treasure. Indeed, in 1899, they were among the earliest landscapes to be featured on Mexican postage stamps.

In 2012, we reported that Greenpeace demands action to clean up Mexico’s surface waters. Greenpeace activists chose to protest at the Juanacatlán Falls to call attention to the poor quality of Mexico’s rivers and lakes. The activists cited government statistics showing that 70% of Mexico’s surface water was contaminated, mostly from toxic industrial dumping, rather than municipal sewage.

Last year, we returned to the theme and looked at how the Juanacatlán Falls had been transformed from the “Niagara of Mexico” to the “Silent River”.

Our concluding paragraph on that occasion bears repeating:

Is it too much to hope that the government, corporations and society in the El Salto area can all come together to remedy this appalling tale of willful mismanagement? Local residents are right to insist on the enforcement of existing water quality regulations and on the implementation of remedial measures to reverse the decline of this major river and its once-famous waterfalls. Even more importantly, urgent measures are needed to reverse the deteriorating public health situation faced by all those living or working nearby.

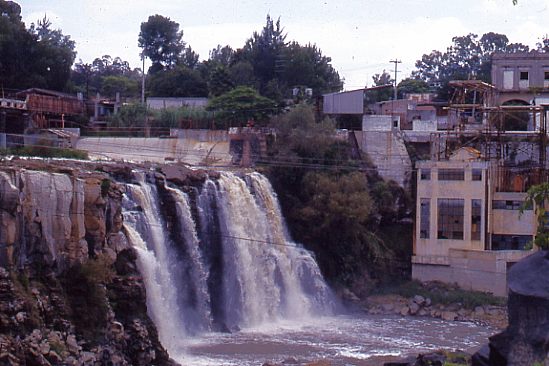

Finally, some good news. Author and activist John Pint, who has done far more than most to publicize the scenic wonders of Western Mexico (including dozens of places that fall way outside the usual tourist guides) reports that the inflow from the 66-km-long Ahogado River, one of the rivers that feeds into the Santiago River just before the Juanacatlán Falls is being cleaned up, with a dramatic, positive impact on the beauty of the Falls themselves. According to Pint’s first-hand report and photographs – Is Guadalajara’s most infamous waterfall now clean? – the smelly, toxic foam that has marred the Falls for decades has become a thing of the past. While this does not mean the water is completely clean, it is certainly an encouraging start.

The Ahogado River itself continues to receive pollutants, and its water remains heavily contaminated, but a 300-million-peso treatment plant, which apparently began operations in 2012, is removing some of the worse contaminants prior to the river joining the Santiago River. There is still a lot of work to be done here if the Juanacatlán Falls are going to be restored to their former pristine beauty, but Geo-Mexico is delighted to hear that progress is (finally) being made.

What a shame that it took the death of eight-year-old Miguel Ángel López in 2008, and years of adverse effects on the health of local inhabitants, before federal and state authorities took decisive action. Later this year, Geo-Mexico hopes to revisit the Falls for the first time in twenty years to see just how much they’ve improved. Watch this space!

Related posts:

- The “Niagara of Mexico”, the Juanacatlán Falls near Guadalajara

- The River Santiago and the Juanacatlan Falls: from the “Niagara of Mexico” to the “Silent River”

- Earliest landscapes on Mexican postage stamps

- Mexico’s freshwater aquifers: undervalued and overexploited

- Greenpeace demands action to clean up Mexico’s surface waters (Apr 2012)