In an earlier post—Can Mexico’s Environmental Agency protect Mexico’s coastline?— we took a critical look at proposals for a tourism mega-development near Cabo Pulmo on the eastern side of the Baja California Peninsula. Cabo Pulmo (see map), a village of about 120 people, is about an hour north of San José del Cabo, and on the edge of the Cabo Pulmo National Marine Park (CPNP).

Jacques Cousteau, the famous ocean explorer, once described the Sea of Cortés as being the “aquarium of the world.” The protected area at Cabo Pulmo, ideal for diving, kayaking and snorkeling, covers 71 sq. km of ocean with its highly complex marine ecosystem.

Jacques Cousteau, the famous ocean explorer, once described the Sea of Cortés as being the “aquarium of the world.” The protected area at Cabo Pulmo, ideal for diving, kayaking and snorkeling, covers 71 sq. km of ocean with its highly complex marine ecosystem.

Cabo Pulmo is on the Tropic of Cancer, about as far north as coral usually grows. The water temperatures vary though the year from about 20 to 30 degrees C (68 to 86 degrees F).

The seven fingers of coral off Cabo Pulmo comprise the most northerly living reef in the eastern Pacific. The 25,000-year-old reef is the refuge for more than 220 kinds of fish, including numerous colorful tropical species. Divers and snorkelers regularly report seeing cabrila, grouper, jacks, dorado, wahoo, sergeant majors, angelfish, putterfish and grunts, some of them in large schools.

On my last visit to Cabo Pulmo in 2008, local fishermen and tourist guides regaled me with positive comments about the success of the National Marine Park, and the area’s recovery since the area was first protected in 1995. Ever since, I’ve wondered how much their positive take was due to wishful thinking, and how much was due to a genuine recovery in local ecosystems. My doubts have been answered by the publication of Large Recovery of Fish Biomass in a No-Take Marine Reserve in the Public Library of Science (PLoS) ONE journal. The article’s authors present compelling evidence, based on fieldwork, that the area has undergone a remarkable recovery.

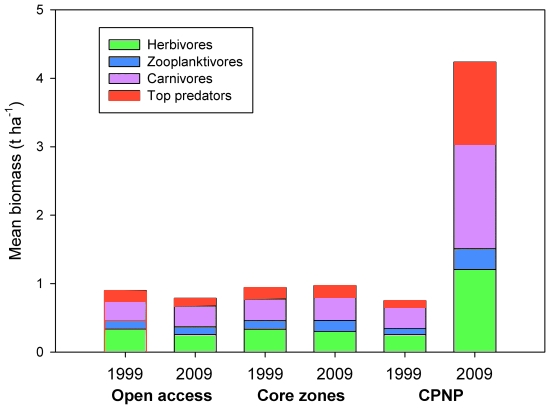

The graph above shows the changes in biomass for three distinct zones of the Sea of Cortés. The open access areas allow commercial fishing. The “core zones” are the central areas of other Marine Parks in the area, including those near Loreto, north of Cabo Pulmo. The CPNP is the Cabo Pulmo National Marine Park, where no fishing is allowed. Clearly, since the CPNP was established, the number and weight of fish inside the park boundaries really have increased rapidly.The total amount (biomass) of fish increased by a staggering 460% over 10 years.

The major reason for the success of the CPNP has been the strength of local residents in undertaking conservation initiatives, and their cooperative monitoring and enforcement of park regulations, sharing surveillance, fauna protection and ocean cleanliness efforts.

The Cabo Pulmo National Marine Park is perhaps the world’s best example of how local initiatives can lead to genuine (and hopefully permanent) environmental protection. The researchers describe it as “the most robust marine park in the world” and say that “The most striking result of the paper… is that fish communities at a depleted site can recover up to a level comparable to remote, pristine sites that have never been fished by humans.”

Here’s hoping that the residents of other parts of Mexico’s coastline threatened by fishing or tourism developments take similar actions and manage to achieve equally positive results for their areas.

Citation:

Aburto-Oropeza O, Erisman B, Galland GR, Mascareñas-Osorio I, Sala E, et al. (2011) Large Recovery of Fish Biomass in a No-Take Marine Reserve. Public Library of Science (PLoS) ONE 6(8): e23601. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0023601

Further reading:

For an exceptionally informative series of papers (in Spanish) on all aspects of tourism and sustainability in Cabo Pulmo, see Tourism and sustainability in Cabo Pulmo, published in 2008 (large pdf file).

Another valuable resource (also in Spanish) is Greenpeace Spain’s position paper entitled Cabo Cortés, destruyendo el paraíso (“Cabo Cortés: destroying paradise”) (pdf file)

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.