One year on from when we last reported on the desperate plight of Mexico’s “little sea cow”, the endangered vaquita marina, where are we now?

According to the World Wildlife Fund, “The vaquita is at the edge of extinction”. The latest population estimate suggests that the number of vaquita in the wild has fallen from about 100 in 2014 to just 60 today, despite a much-publicized ban on fishing in the main area where the little sea cows are found.

As we reported in Mexico’s “little sea cow” on the verge of extinction two years ago, the sea cow’s fate is inextricably tied to fishing for the (also endangered) totoaba, a fish in demand in China for its swim bladder, which is believed to have medicinal properties. Fishermen in Mexico’s Gulf of California (Sea of Cortés) are reported to have been offered more than $4,000 for a single totoaba bladder, which weighs only 500 grams. The price in China is reported to be between $10,000 and $20,000 each.

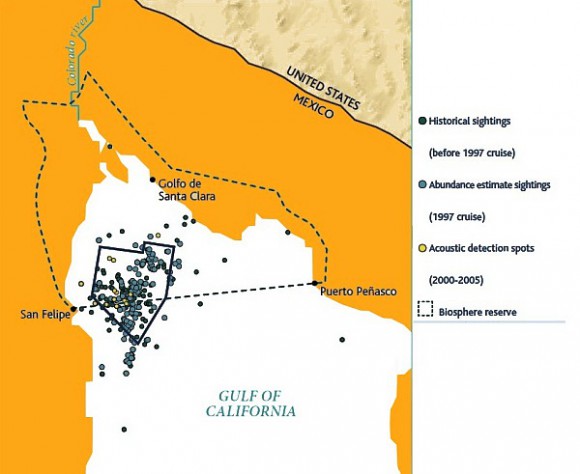

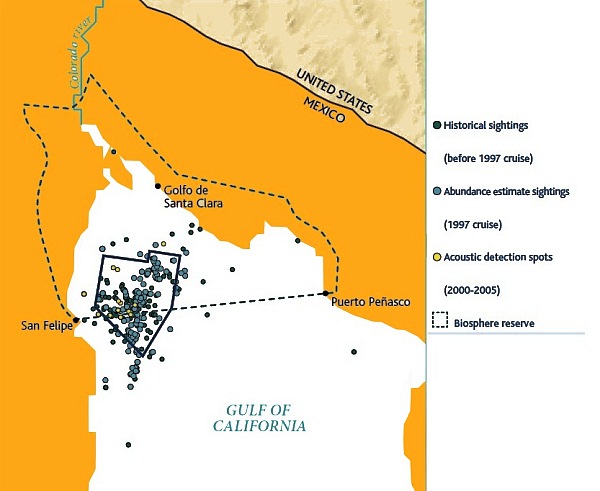

Map of sightings and acoustic detection spots. Adapted from North American Conservation Action Plan for the vaquita

In April 2015, federal authorities imposed a two-year ban on gillnets and expanded the vaquita protection area to cover 13,000 square kilometers (5,000 square miles) of the upper Gulf of California . Some 600 gill nets (each of which can be up to # meters long) were seized by the Mexican Navy in 2015 (and 77 individuals detained), and navy personnel claim they are still confiscating nets every day.

The International Committee for the Recovery of the Vaquita (CIRVA) is trying to make a difference. Among the options being considered by Mexico’s Environment Secretariat (Semarnat) is assisted breeding, though a vaquita expert, Barbara Taylor of the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, is quoted in The Guardian as claiming that “We have no idea whether it is feasible to find, capture and maintain vaquitas in captivity much less whether they will reproduce. The uncertainties are large.” The World Wildlife Fund Mexico is currently opposed to such a strategy, given the very low number remaining.

Mexico has had conservation successes in the past, allowing the populations of other marine animals, including the Guadalupe fur seal and the northern elephant seal, to recover.

Related posts:

- Mexico’s “little sea cow” on the verge of extinction

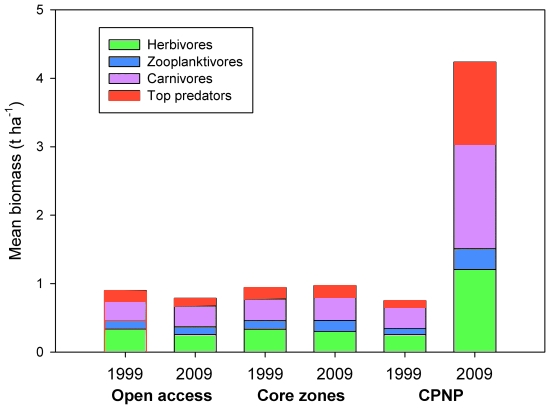

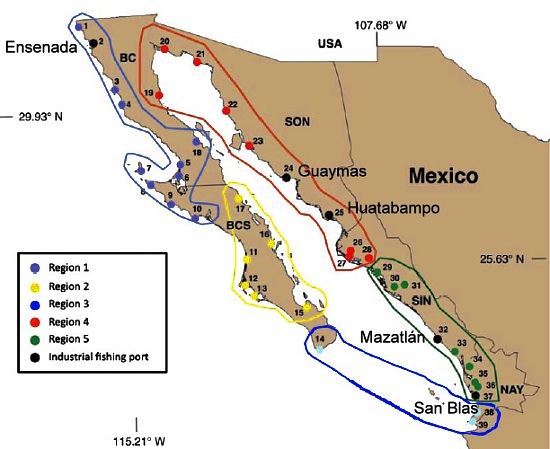

- Overfishing in Mexico’s Sea of Cortés (Gulf of California)

- How sustainable is commercial fishing in northwest Mexico?

- The extraordinary ecological recovery of Mexico’s Cabo Pulmo Marine Park

- Good news for Mexico’s little sea cow, the vaquita marina

Jacques Cousteau

Jacques Cousteau