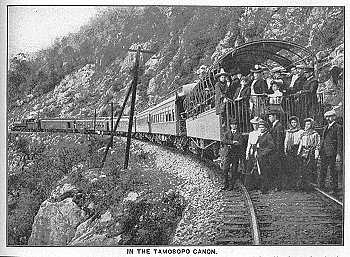

In the golden age of steam, railway lines were built all over Mexico. Rail quickly became THE way to travel. Depending on your status and wealth, you could travel third class, second class or first class. Anyone desiring greater comfort and privacy could add their luxury carriage to a regular train. To avoid mixing with the ordinary folk, the super-rich and the privileged few hired or ran their own special trains.

The railway era ushered in an entire new genre of travel writing, which culminated in the first genuine guidebooks, describing routes and places that other travelers could visit with relative ease. The earliest comprehensive guide to Mexico was Appletons’ Guide to Mexico (1883); it was soon followed by several others including Campbell’s Complete guide and descriptive book of Mexico, first published in 1895.

The 1899 edition of Reau Campbell’s famous Guide provides an idea of what visitors to Cuautla in the state of Morelos, for example, could expect when the train was in its heyday:

Here again the tourist finds another feature of Mexico’s scenery and people, totally different from all the other travels in the Republic. The houses are adobe as to walls and thatched as to roofs; the broad plains have curious trees; bands of Indians troop from one town to another in curious costumes, marching along totally oblivious to the passing locomotive and approaching civilization, and will not give way to the latter any quicker than they will to the engine if they happen to be on the track when it comes along. In fact, it is hard for them to understand that the train cannot “keep to the right” when it meets people in the road, and they claim the right of way from the fact that they were there first.

A decade later, the British-born journalist William English Carson (1870-1940) spent four months in Mexico. Carson also visited Cuautla, on the advice of a doctor as the result of catching influenza.

Upon making inquiries at the railway office about trains to Cuautla, the clerk handed me an illustrated pamphlet with a fine colored picture on the cover representing a Mexican tropical scene. It bore the title, “Cuautla, Mexico’s Carlsbad.” What! I thought, another Carlsbad? In glowing language the booklet described Cuautla as an earthly paradise with a magnificent climate, beautiful scenery, splendidly equipped hotels and a warm sulphur spring whose waters were a certain specific for almost every human ailment. What more could one desire?

Cuautla is about a hundred miles or so from Puebla, and the speedy trains of the Interoceanic Railway take about ten hours to make the journey. The train which I took left about seven o’clock in the morning ; it was not timed to reach Cuautla until five in the evening; and as there was not any restaurant at any intermediate station, a somewhat terrifying prospect of starvation faced travellers. How were they to get their luncheon? A little pamphlet given away by an American tourist agency and evidently written by an accomplished press-agent gave me the desired information: “At a certain station on the road,” said my traveller’s guide, “your train will stop for some twenty minutes. Here you will be greeted by graceful Indian women,— beauties, many of them, with their olive skins and dark, flashing eyes, bearing themselves with queenly grace in their dainty rebosos and flowing garments, white as the driven snow. They will offer you such dainties as tamales, chili-con-carne and tortillas, piping hot from their little stoves, and prepared with all the scrupulous cleanliness of a Parisian chef. They will bring you dainty refrescos of freshly gathered pineapple or orange to quench your thirst, and pastry such as your mother may have made when her cooking was at its prime.”

Now, what more could any reasonable traveller demand? What need was there for a restaurant when there were all these good things to be enjoyed? I showed my guide to an American friend before I started. He chuckled, gave a knowing wink and remarked, “Great is the faith of man, for after all your experiences you can still believe in a Mexican guide-book.”

Hotels were not always the same standard as those in the USA, but were certainly less expensive:

The attractions of the hotel were hardly up to those of a Carlsbad establishment, for it had neither a writing nor a smoking room; but the terms were rather more attractive than the usual Carlsbad tariff, being about two dollars a day inclusive. It is true there was a good deal of Mexican about the cooking, but the meals were not at all bad and the service very fair…

Railways may have opened up Mexico for tourism, but today, sadly, there are virtually no passenger lines still operating, the main exception being the justly famous Copper Canyon line from Los Mochis to Chihuahua.

Sources:

Campbell, Reau. Campbell’s New Revised Complete Guide and Descriptive Book of Mexico. Chicago. 1899.

Carson, William English. Mexico: the wonderland of the south. 1909

This is an edited version of an article originally published on MexConnect.

Click here for the complete article

The growth of the railway network and the importance of railways in Mexico are examined in depth in chapter 17, and tourism in Mexico is the subject of chapter 19. of Geo-Mexico: the geography and dynamics of modern Mexico.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.