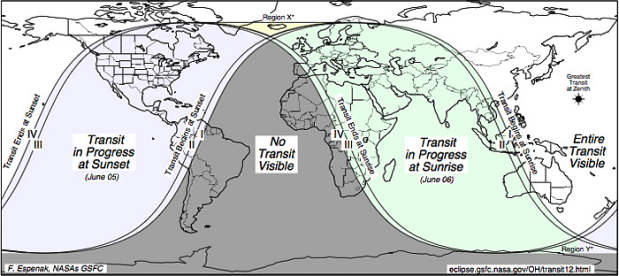

Next week, clear skies permitting, a Transit of Venus will be visible from all of Mexico (as well as the USA, most of Canada, etc). During a transit of Venus, the planet Venus passes slowly in front of the sun from the perspective of a viewer on Earth.

CAUTION: Never observe the sun directly, even during a transit of Venus, or your eyesight may be permanently damaged. Transit viewers should take similar precautions to those needed to observe an eclipse.

Such events are rare. This will likely be the last chance to see one in your lifetime since the next transit of Venus will be in more than 100 years time!

Back in the eighteenth century, scientists from France anxious to observe the 1769 transit of Venus were forced to seek permission from Spain to join a party of Spanish astronomers setting up a temporary observatory in a Spanish colony which was predicted to offer the best views. These astronomers congregated at a site very near the present-day settlement of San José del Cabo on the southern tip of the Baja California peninsula. A short distance away, a creole astronomer Joaquín Velázquez de León, who had traveled from Mexico City, set up camp to make his own independent observations. Scientific trips at this time were not without their perils; only days after the transit, three members of the Franco-Spanish party, including the two principal astronomers, died after contracting yellow fever.The next transit of Venus occurred in the year 1874. Mexico has a particular connection to this transit. To observe this event, and take scientific measurements, Mexico’s first ever international scientific expedition was undertaken. A distinguished group of Mexican scientists traveled to Japan to study this event. By the time they returned, they had been all the way around the world.

- Mexico’s international scientific expedition to observe the 1874 transit of Venus

- The route taken by Mexico’s first international scientific expedition, 1874-5

Mexico has a long history of astronomy. Several indigenous groups, including the Zapotecs in Oaxaca and the Maya in the Yucatán Peninsula undertook sophisticated astronomical observations, enabling the successful prediction, not only of annual events such as the summer solstice, but also of longer-term phenomena such as eclipses. Mexico (admittedly not called that at the time!) hosted one of the earliest international astronomical conferences in the world.

According to some, the Maya predicted that the world will come to an end on 21 December next year. The claims are based on the fact that the current Maya calendar cycle “ends” on that day. The Maya have several simultaneous calendar counts. Each long cycle count, or B’ak’tun, lasts 394.3 years. The very first B’ak’tun began on 11 August 3114 BC, the date when the Maya believe they were created. The 13th B’ak’tun ends on 21 December 2012, hence the concern propagated by panic-mongers.

The Maya themselves don’t seem too worried by these alarmist claims. They worked out years ago that their 14th B’ak’tun cycle will start the next day, 22 December 2012, and run to sometime in 2406. On the other hand, is it just a simple coincidence that on 21 December 2012, at the exact moment of the winter solstice at 23:11 UST, the sun will be precisely aligned with the center of the Milky Way galaxy, as seen from Earth— the first time this has happened for 26,000 years?

Will the claims be proven true? Unlikely, but perhaps we won’t plan to write any posts about the geography of Mexico for publication after 22 December 2012 until we’re absolutely sure…

Need more evidence about the Maya prediction? As a starting-point, try:

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.