Corn (maize) has been the principal food of the Tarahumara Indians since long before the Spanish arrived in Mexico. There are several precolumbian varieties that are still grown, including the ancient and delicious “blue corn”. Maize is the source of a wide variety of foodstuffs and drinks including flour (pinole), a non‑alcoholic drink called esquiate, tortillas, atole and tamales. Green corn and blue corn tortillas are made when in season, for special occasions. A version of corn beer (Spanish “tesgüino“) is also important, and is described separately below.

The Tarahumara continue to “hunt and gather” locally available foodstuffs, though these activities now supply only about 10% of their diet. Several varieties of cactus fruit are collected, edible agaves are cooked, and small river fish are caught where possible. Small animals are ruthlessly hunted. Squirrels, birds and deer, though rare today, are considered particular delicacies.

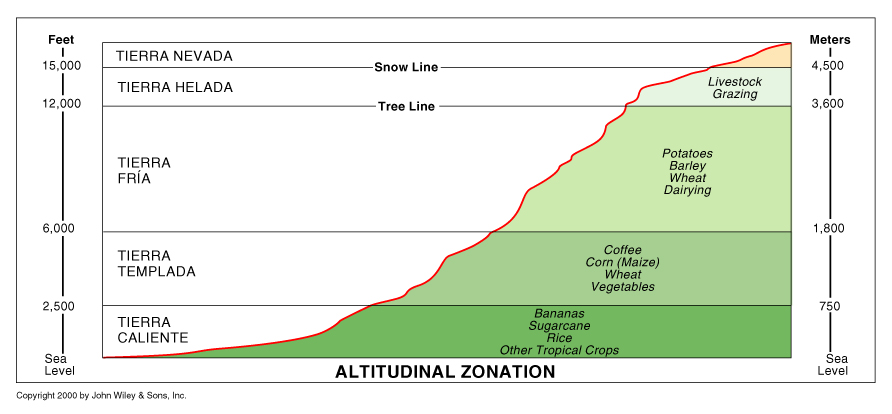

Beans, mustard green and squash also play important parts in the Tarahumara diet which is rounded out by wheat, potatoes, peaches and sweet potatoes. Those Tarahumara with access to lower elevations, such as Batopilas Canyon, also include crops typical of warmer regions such as oranges, figs and sugar‑cane. Chiles and tobacco are also cultivated.

Meat is hard to come by, and eaten only on ceremonial occasions when a goat or cow is sacrificed. It probably accounts for less than 5% of the average Tarahumara diet. Most protein comes from beans; these are usually prepared by roasting, grinding and then boiling with water, to produce a hot soup. Pork, chicken and eggs are rarely found, while sheep are kept mainly for their wool.

Squash is only eaten in season though the Indians know how to preserve it by drying. The squash flowers are eaten too, boiled with water and salt. Mustard greens (Tarahumara “maquasori“, Spanish “quelites“) are grown in the rainy season and carefully gathered and dried, for use throughout the year, providing minerals and vitamins. Quelites include the epazote plant (Chenopodium ambrosioides), described by Diana Kennedy, the world’s foremost authority on Mexican cuisine, as “the Mexican herb par excellence”.

Many families have a small number of scrubby fruit trees, usually peaches, near their house. Fruit is often picked and eaten green. Peaches are an important trading item, and may be exchanged for cigarettes or cloth. At higher elevations, apples are grown.

Given the well-documented endurance feats of Tarahumara runners, this diet clearly provides adequate nutrition! In the 1994 Denver, Colorado, “Sky Race”, Tarahumara Indian Juan Herrera (25 years old) smashed 25 minutes off the previous record, completing the 160 kilometers in 17 hours, 30 minutes, 42 seconds. He came in more than half an hour ahead of his nearest rival!

However, in many years (including 2011, 2012), and seemingly with increasing frequency, food is in extremely short supply by the time the summer growing season arrives. Fortunately for the less successful Tarahumara farmers, an age‑old tribal custom,

korima is still observed. This custom requires the better‑off to share food with the less fortunate in times of need. The poor person visits successive

ranchos, collecting small quantities of food to last him a week or two, then repeats this procedure as necessary. No lasting debt is incurred. The severe drought in northern Mexico over the past 24 months – see

Many states in Mexico badly affected by drought – has meant that many Tarahumara have no food reserves left and have had to rely on infrequent emergency aid organized by charitable organizations, and the federal and state government.

Tesgüino (corn beer)

The average Tarahumara family expends 100 kg of corn a year to make tesgüino. This is sufficient corn to last a family of 4‑5 about a month, a significant quantity, given the regular annual food deficiencies in this region.

Tesgüino is a form of corn‑beer. It is a thick, milky, nutritious drink, supplying much needed vitamins, minerals and calories. The corn is first dampened and allowed to sprout in a dark place, then ground and boiled for about 8 hours with a catalyst to promote fermentation. The catalyst may be local grass seed (basiahuari) ground in a metate, or bark, leaves, lichens or roots, depending on the place. The liquid is then strained and left to ferment for about three days. The total preparation time is therefore about seven days. To avoid spoilage, the beverage must be drunk quickly. It’s at its best for only 12‑24 hours. This explains why it would be so wasteful to leave any corn beer tesgüino undrunk at a “tesgüinada” (see below); it would be far too wasteful, even if as many as 50 gallons have been made.

Other alcoholic drinks are also made, one based on green corn (pachiki or caña) and another on maguey (meki). In earlier times, there were no alcoholics as we define the term, since tesgüino can’t be stored, but today the greater availability of commercial alcohol poses a serious problem.

Why are tesgüinadas so important?

The tesgüinada system is the social device which ties individual settlements (ranchos) together in a cooperative framework for performing all kinds of agricultural tasks. The person requiring assistance with a particular task will invite his neighbors and friends to a “tesgüinada”. He takes responsibility for providing the tesgüino, other refreshments and food. In return, the persons who attend will help plow. sow, reap or weed..

Lumholtz, recognizing from his time among the Tarahumara at the end of the last century the importance of the tesgüinada, summed up their philosophy writing that, “Rain cannot be obtained without tesgüino. Tesgüino cannot be made without corn and corn cannot grow without rain.”

The tesgüinada is necessary since many families cannot supply the labor required for both herding and cultivation at certain times of the year. In small groups like the ranchos, high mortality inevitably leaves some families unable to manage on their own. The tesgüinada is their response to the economic uncertainties facing them just as collective religious rituals help them face the unpredictability of weather, sickness and plagues. The cooperative effort moves from one rancho to another, from one tesgüinada to the next.

The tesgüinadas, which are like large, boisterous parties, provide a focus for Tarahumara social life, a chance for entertainment and to make extra-familiar friendships. Being held in a succession of different ranchos, they offer some communal resilience against the risks of becoming further isolated and marginalized. The Tarahumara attach no shame to being drunk; indeed, they positively revel in getting as drunk as humanly possible at tesgüinadas. Children are excluded until they are 14 years old or so.

Tesgüinadas do come at a cost. They increase the incidence of accidents, such as adult men falling off precipitous rock ledges that would normally pose little risk, even when running. They increase violence, which may result in serious injury or death. They also limit the amount of corn that can be held over from one year to the next. Assuming an average of 4‑6 tesgüinadas per year per family, with additional visits to tesgüinadas held in perhaps 15 other households, many Tarahumara Indians would be likely to attend more than sixty tesgüinadas a year. Even if the true figure is only 50% of this total, it still means that the Tarahumara spend as many as 100 days a year either preparing for a tesgüinada, attending one, or recovering from one.