The short answer to “What is the elevation of Mexico’s cities?” is “somewhere between zero and 3000 meters (8200 ft) above sea level!” Mexico’s extraordinarily varied relief provides settlement opportunities at a very wide range of elevations. Many Mexican cities are at or near sea level. This group includes not only coastal resort cities such as Acapulco, Cancún and Puerto Vallarta, but also Tijuana on the northern border and, at the opposite end of the country, Mérida, the inland capital of Yucatán state.

Mexico City, the nation’s capital, has an average elevation of about 2250 meters (7400 ft.), similar to that of nearby Puebla. Toluca, the capital city of the state of México, is almost 400 m higher, while both Huixquilucan and Zinacantepec (also in the state of México) are at an elevation of over 2700 meters. Moving northwards from Mexico City, numerous major cities are at elevations of between 1500 meters and 1850 meters above sea level. The cities nearer the lower end of this range include Saltillo, Oaxaca and Guadalajara, while Aguascalientes, Querétaro, Guanajuato, Morelia and León are all situated at elevations close to 1800 meters.

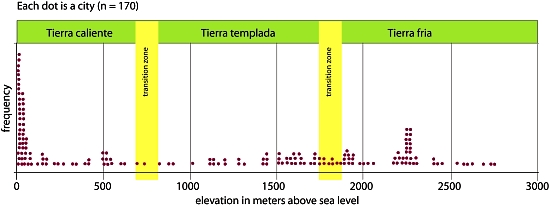

Frequency plot of city elevations in Mexico. Credit: Geo-Mexico

Are there more cities at some elevations than others? Each dot on the graph above represents one of Mexico’s 170 largest cities and towns, plotted against its average elevation. The two major clusters of cities occur at elevations of close to sea level and at 2250 meters, with another smaller, more spread out cluster between 1500 meters and 2000 meters. Perhaps somewhat surprisingly, there are relatively few Mexican cities at elevations of between 100 and 1500 meters (4920 ft.).

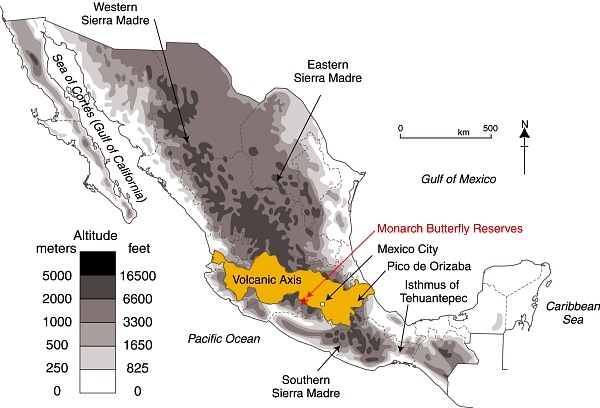

- Q. Can you suggest any reasons for this? [Hint: Look at a relief map of Mexico to see how much land surface there actually is at different elevations].

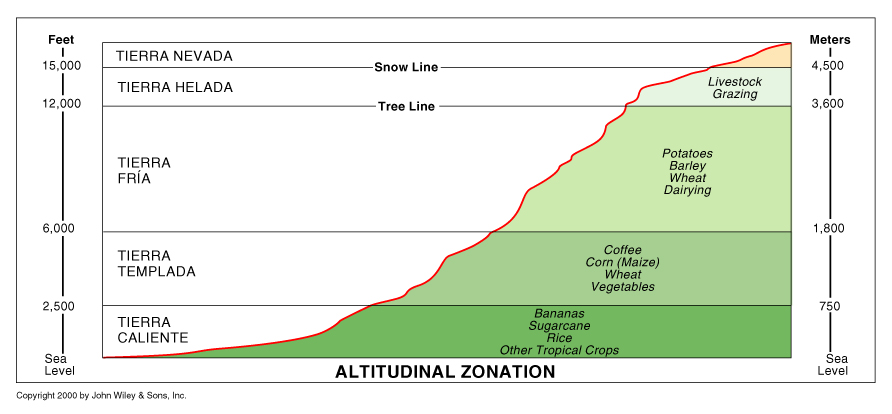

The graph also shows the division of Mexico’s climate and vegetation zones by elevation first proposed by Alexander von Humbuldt following his visit to Mexico in 1803–1804. The terms tierra caliente, tierra templada, and tierra fría are still widely used by non-specialists today to describe the vertical differentiation of Mexico’s climatic and vegetation zones (see cross-section below).

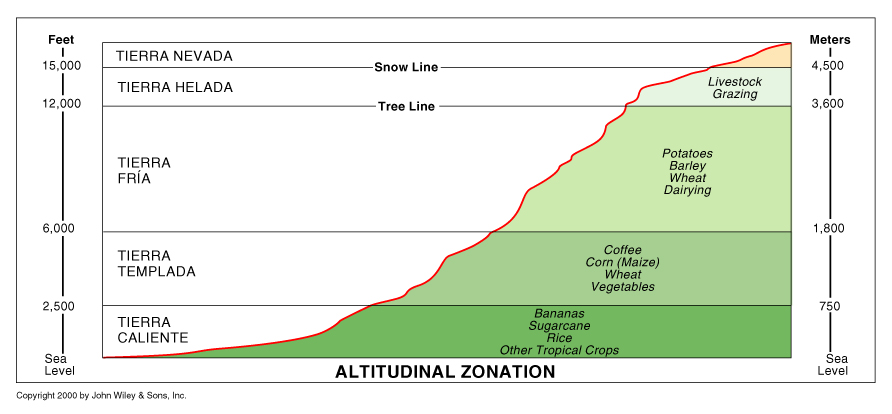

Altitude zones. Copyright John Wiley & Sons Inc. 2000.

The tierra caliente (hot land) includes all areas under about 900 m (3000 ft). These areas generally have a mean annual temperature above 25°C (77°F). Their natural vegetation is usually either tropical evergreen or tropical deciduous forest. Farms produce tropical crops such as sugar-cane, cacao and bananas. Tierra templada (temperate land) describes the area between 900 and 1800 m (3000 to 6000 ft) where mean annual temperatures are usually between about 18°C and 25°C (64°F to 77°F). The natural vegetation in these zones is temperate forest, such as oak and pine-oak forest. Farms grow crops such as corn (maize), beans, squash, wheat and coffee. Tierra fria (cold land) is over 1800 m (6000 ft) where mean annual temperatures are in the range 13°–18°C (55°–64°F). At these altitudes pine and pine-fir forests are common. Farm crops include barley and potatoes. On the highest mountain tops, above the tierra fría is tierra helada, frosty land.

Interestingly, the tierra templada appears to have fewer cities than might be expected. Equally, while archaeologists have sometimes argued for the advantages of siting settlements close to the transition zone between climates, where a variety of produce from very distinct climates might be traded, the graph shows no evidence for this.

It would be misleading to read too much into this superficial analysis of the elevations of Mexican settlements. First, we have only considered the 170 largest settlements. Second, an individual settlement may extend over a range of elevation, so using an average figure does not reveal the entire picture. Thirdly, the precise elevations for tierra caliente, templada and fria all depend on the latitude and other local factors. Even so, it might be interesting to extend this analysis at some future time to include far more settlements to see if the patterns identified are still present or if others emerge.

Related posts: