This short Postandfly video of an area known as Peñas Cargardas (“Loaded Rocks”) in the state of Hidalgo is the perfect excuse to add to our posts about Mexico’s geomorphosites – sites where landforms have provided amazing scenery for our enjoyment. This area of Mexico is definitely one of my favorites, partly because it is crammed with interesting sights for geographers, including the Basalt Prisms of San Miguel Regla, only a few kilometers away from the Piedras Cargadas, and an equally-stunning geomorphosite.

A few minutes east of the city of Pachuca, the Peñas Cargadas (sometimes called the Piedras Cargadas) are located in a valley in the surrounding pine-fir forest. The rocks comprising the Peñas Cargadas have capricious shapes; some appear to be balanced on top of others. Their formation may well be due to the same processes that formed the Piedras Encimadas in Puebla, which are actually not all that far away as the crow flies.

The nearest town, Mineral del Monte (aka Real del Monte) has lots of interest for cultural tourists. Among many other claims to fame, it was where the first soccer and tennis matches in Mexico were played ~ in the nineteenth century, when the surrounding hills echoed to the sounds of Cornish miners, brought here from the U.K. to work the silver mines.

The miners introduced the Cornish Pasty, chile-enriched variations of which are still sold in the town as pastes. Real del Monte also has an English Cemetery, testament not only to the many tragic accidents that befell miners when mining here was at its peak, but also to the long-standing allegiance that led many in-comers to remain here to raise their families long after mining was in near-terminal decline. The town has typical nineteenth century mining architecture. The larger buildings retain many signs of their former wealth the glory.

The following Spanish language video has some ground-level views, as well as more information about the scenery and the area’s flora:

How to get there

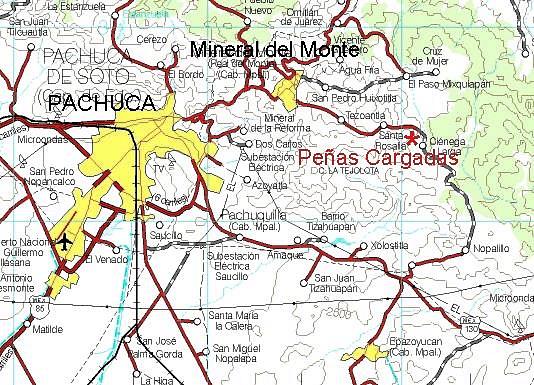

The Peñas Cargadas are about ten kilometers east of Pachuca (see map). From Pachuca, follow signs for Mineral del Monte, and then drive past the “Panteón Inglés” (English Cemetery) in that town on the road to Tezoantla. The Peñas Cargadas are about 3.5 kilometers beyond Tezoantla. This is a great place for a day trip from Mexico City.

Related posts:

- Geotourism and geomorphosites in Mexico

- The Basalt Prisms of San Miguel Regla, Hidalgo

- Piedras Encimadas in Puebla

- The Piedras Bola (Stone Balls) of the Sierra de Ameca, Jalisco

- Peña de Bernal, a monolith in Querétaro

- The crater lake of Santa María del Oro in Nayarit

- How were the Piedras Encimadas (Stacked Rocks) in Puebla, Mexico, formed?