Mexico has some of the finest markets in the world. The variety of produce and other items sold in markets is staggering. But not all Mexican markets are the same. The two major groups are the permanent markets (mercados), usually housed in a purpose-built structure and open for business every day, and the street market or tianguis, usually held once a week.

Street market in Oaxaca. Photo: Tony Burton

Most tianguis temporarily occupy one or more streets or a public square, though some also use privately-owned land. The origins of the tianguis lie in pre-Columbian times, whereas mercados are a much more recent innovation. In this post, we focus on the tianguis.

The geography of a street market or tianguis

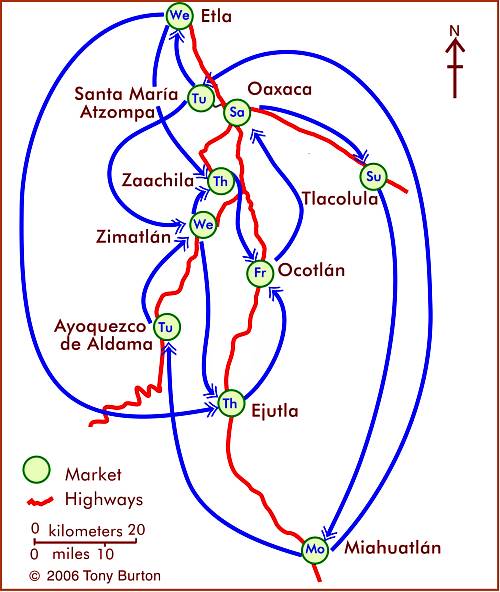

The merchants selling goods in a street market generally visit several markets each week, on a regular rotation (see map for an example of a weekly cycle of markets around the city of Oaxaca). In terms of economic geography, weekly markets allow merchants to maximize their “sphere of influence” and exceed the sales “threshold”, the minimum sales required for them to make a profit, even if they are selling items that may not cost very much, and for which individual consumers are not prepared to travel very far. By visiting, say, four markets a week, these merchants effectively quadruple their potential customers. In terms of social and human geography, these weekly markets are a valuable means of communication, and news from one community quickly travels, via the merchants, to another.

At the same time, these markets give consumers access to a much wider range of goods than would otherwise be possible.

The map shows the market day for major markets, and the major weekly marketing cycles, in the area around the city of Oaxaca. With the exception of Oaxaca city (population 480,000) and Miahuatlán (33,000), all the other towns have populations between 13,000 and 20,000. The merchants at such markets generally carry their wares from village to village on the days of their respective markets. Some local farmers also sell their produce at such markets. For more details, see Markets in and near the city of Oaxaca.

The weekly cycle of markets in and around the city of Oaxaca, Mexico. Map: Tony Burton. All rights reserved.

Mexico has a very long history of street markets, certainly dating back more than two thousand years. The Spanish conquistadors saw, first hand, the very large market of Tlatelolco, in what is now Mexico City, which attracted between 40,000 and 45,000 people on “market day”, which was held every five days.

Markets enabled people living in one region to trade goods produced in another region. In the case of food items this allowed residents of the “hot lands” (tierra caliente) to gain access to food items coming from the “temperate lands” (tierra templada). Some ancient settlements in Mexico are located close to the division between either tierra caliente and tierra templada [usual elevation about 750 meters above sea level] or tierra templada and “cold lands” (tierra fria), at an elevation of about 1800 meters a.s.l. These locations clearly favored the trading and exchanging of items from one major climate zone to another.

Food was by no means the only item traded in markets. Many plants with medicinal value were traded, as were others used for construction materials. It was also common to trade textiles, minerals and household items such as baskets, ceramics and grinding stones, as well as salt, prized feathers and animals.

Even today, most Mexican markets have a distinctive spatial pattern of stalls, with vendors of similar items setting up side-by-side, allowing for comparison shopping. It is a relatively easy and revealing fieldwork exercise to map a Mexican market and then analyze the distribution of different kinds of goods.

We looked in a previous post at how the same basic principle applies to the distribution of shops in many towns and cities.

While most markets traded a variety of items, a handful of specialist markets emerged, especially in the Mexico City area. For example, there were specialist markets for salt in Atenantitlan, dogs (as a source of food) in Acolman, and for slaves in Azcapotzalco and Iztocan.

In a future post, we will look at the origins of the tianguis in the Oaxaca region, a region that is still one of the most fascinating areas in Mexico for markets of all kinds.

Further reading:

Related posts: