In a previous post – Mexico’s shoe (footwear) manufacturing industry: regional clustering – we looked at the concentration of the shoe-manufacturing industry in three major areas: León (Guanajuato), Guadalajara (Jalisco) and in/around Mexico City. We have also taken a look at Mexico’s international trade in shoes – Mexico’s footwear industry: imports and exports. We now turn our attention to the distribution of shoe retailers within a large Mexican city.

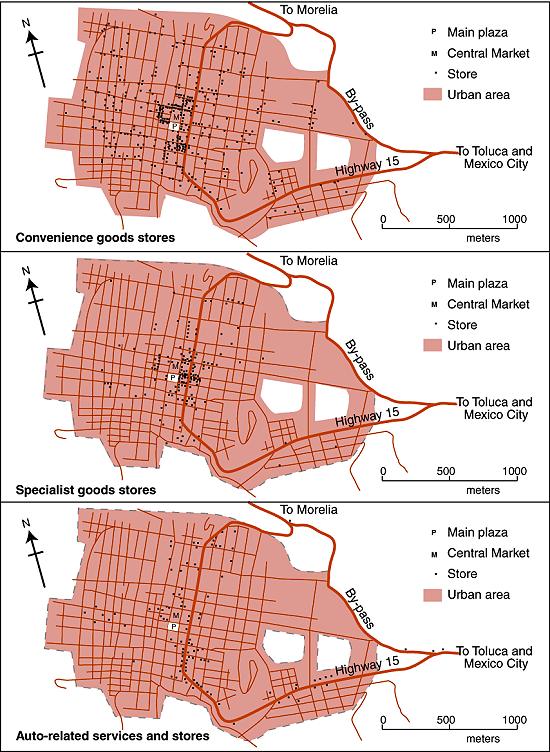

The retailing of shoes within cities often exhibits distinctive spatial patterns. Many older and larger Mexican cities tend to have all the retailers for a particular item (furniture, electronics, autoparts, etc) concentrated in a very small area. For example, dozens of retail outlets for electronics are located within a few blocks of Mexico City’s main square or zócalo. Electronics stores are in very close proximity to one other, and occupy both sides of the street for several blocks, leaving little or no room for any other retailers.

Another example of retail specialization is Corregidora street, which has several blocks dedicated to the sale of pots and pans, kitchen utensils and table settings.

Elsewhere in Mexico City’s downtown area:

… turn right and continue down Chile street to the intersection with Tacuba street. One of the most fascinating aspects of commercial life in the downtown area of Mexico City is that each area is specialized in some trade or retail activity. Such trading ghettos were also a feature in Tenochtitlán and the practice still exists today. Where you are now walking is the barrio of bridal shops. The greatest concentration of these shops is north of the Heras y Soto House…” (Candace Siegle, Walking through History, a series of walks through Mexico City’s historic center, 1989)

Returning to the subject of shoes, without which no bridal outfit is complete, shoe retailing is also often heavily concentrated in certain sections of Mexico’s larger cities. Perhaps the most extreme example is in Guadalajara, where shoe retailing is concentrated in two main zones. One of these zones is within the central business district, and is comprised of both regular storefronts and a market. The other area is several kilometers west of the center, around Galería del Calzado, a shopping plaza of more than 60 stores entirely dedicated to shoes. The Galería, located where Yaquis meets Avenida México, has a total floor space in excess of 8,600 square meters (92,500 square ft). The shops in Galería del Calzado stock every major brand and type of shoe, and eagerly compete for your pesos.

From a consumer’s perspective, this is all highly convenient and allows for easy comparison shopping. However, I have never been convinced of the advantages of such concentration from the point of view of the retail store owners, unless perhaps they get their stock from a relatively limited number of (shared) shoe distributors?

Despite the success of many Mexican shoe manufacturers, one of the fundamental weaknesses of the supply chain for footwear in Mexico (according to sector analysts) is the absence of any strong specialized marketer dedicated to shoes. Fancy a job marketing cowboy boots, anyone?

Related posts:

- León hosts Latin America’s largest trade fair for footwear (2014)

- Mexico’s shoe (footwear) manufacturing industry: regional clustering (2011)

Chapters 21 and 22 of Geo-Mexico: the geography and dynamics of modern Mexico analyze Mexico’s 500-year transition to an urban society and the internal geography of Mexico’s cities. Chapter 23 looks at urban issues, problems and trends. Buy your copy of this invaluable reference guide today!