The Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto, Canada, continues to showcase Mexican textiles in a major exhibition entitled Viva México! Clothing and Culture.

The exhibition opened in May this year and closes 23 May 3, 2016. It occupies the museum’s Patricia Harris Gallery of Textiles & Costume. Even though the museum’s collection of Mexican textiles is one of the largest and most important collections of its kind in the world, very few items from the collection have ever been publicly displayed previously.

“Vibrant expressions of creativity, the pieces in this exhibition combine remarkable technical skill with exquisite artistry. Over 150 stunning historic and contemporary pieces are on display, including complete costume ensembles, sarapes, rebozos, textiles, embroidery, beadwork and more.”

As the promotional material claims, “The evolution of Mexican fashion reflects the history of Mexico, where the textile arts reach back over many centuries. After the Spanish Conquest of 1521, European styles influenced the distinctive clothing of the Maya, the Aztec and other great civilizations. Contemporary Mexican textiles owe their vitality to the fusion of traditions. ¡Viva Mexico! celebrates this rich and enduring cultural legacy.”

The guest curator for this exhibition is Chloë Sayer, a specialist in Mexican popular art and author of numerous works on the subject, including Costumes of Mexico (1985); Arts and Crafts of Mexico (1990); Mexican Patterns: A Design Source Book (1990); Mexico: The Day of the Dead: An Anthology (1993); Mexican Textile Techniques (1999); Textiles from Mexico (2002); and Fiesta: Days of the Dead & Other Mexican Festivals (2009).

Sayer believes, with good reason, that Mexican textile handcrafts should be named a UNESCO cultural heritage, due to their centuries-old history, and because they are still worn by Mexico’s indigenous peoples. She sees the challenge as being how to ensure that “new generations of Mexicans continue to learn how to make these textiles”

The exhibition comprises about 200 pieces, some dating back to the nineteenth century. “The collection tells the story of Mexican textiles through centuries, and that’s why it’s so valuable,” Sayer said. Sessions when visitors to the exhibition can watch Mexican artists hand-crafting traditional textiles are also scheduled on a regular basis.

There are significant regional differences in the “typical” traditional textiles in Mexico. This exhibition delves into the geography of Mexican textiles and brings long-overdue attention to their extraordinary diversity.

Related posts:

- Oaxaca is the most culturally diverse state in Mexico

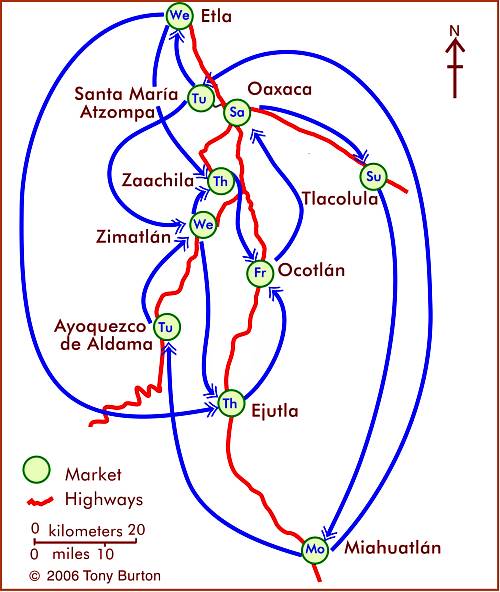

- Markets in and near the city of Oaxaca

- Map of Oaxaca state, with an introduction to its geography

- The geography of the craft towns of Michoacan

- The geography of Mexico’s street markets (tianguis)

- The origins of street markets (tianguis) in Oaxaca, Mexico

- Striking photographs of Oaxaca by Cynthia Roderick