The Sea of Cortés (Gulf of California) is one of the world’s top five seas in terms of ecological productivity and biological diversity. The region is world famous for its recreational sports fishing.

Background to the region’s wetlands

Among rivers feeding the Sea of Cortés are the Colorado, Fuerte and Yaqui. Its coast includes more than 300 estuaries and other wetlands, of which the delta of the Colorado River is especially important. The vast reduction in the Colorado’s flow has negatively impacted wetlands and fisheries.

These wetlands are also threatened by the development of marinas, resorts and aquaculture, especially shrimp farms. The plant and animal communities in these wetlands provide a constant supply of nutrients which support large numbers of fish and marine mammals. These include the humpback whale, California gray whale, blue whale, fin whale, sperm whale and the leatherback sea turtle.

Wetland degradation and declining fish stocks have had inevitable consequences on many marine mammals. Concern over endangered mammals such as the vaquita porpoise, which is endemic to the area and was being taken as by catch in gill nets, led to the establishment of the Biosphere Reserve of the Upper Gulf of California and Delta of the Colorado River in 1993.

The Biosphere Reserve aims to protect breeding grounds and conserve endangered species, including the vaquita, the totoaba, the desert pupfish and the Yuma clapper rail. This was the first marine reserve established in Mexico; several other marine protected areas has since been established on Mexico’s other coasts.

Did changes in technology hasten the decline of commercial fishing?

In the Sea of Cortés, changes in technology, coupled with high demand for fish (especially in Japan), and greed, help to explain the demise of fish stocks.

Commercial shrimp fishing started here in the 1940s. The introduction of outboard motors in the 1970s allowed small fiberglass boats (pangas) to travel further afield in search of fish. Up to 20,000 pangas using gill nets had an immediate adverse impact on fish stocks, with large decreases in roosterfish, yellowtail and sierra mackerel.

In the 1980s, as the sardine stocks close to Guaymas had been depleted, new sardine boats were built with refrigeration facilities which allowed them to catch sardines further offshore, in their feeding grounds near Midriff Island.

In the 1990s a longline fishing fleet began to operate out of Ensenada. Licensed boats were required to fish beyond a non-fishing zone extending 80 km (50 mi) from the coast. A single longline boat may have 5 km (3 mi) of line with 600 to 700 baited hooks in total. The swordfish populations outside the protected zone were quickly depleted, leading fishing boat owners to apply for permits to catch shark inside the 80-km limits.

The Sea of Cortés faces numerous pressures. Decades of commercial overfishing are causing a total collapse of fish stocks. As late as 1993, the area, less than 5% of all Mexico’s territorial waters, produced about 75% of the nation’s total fish catch of 1.5 million metric tons; however, by some estimates, fish populations have declined by 90% since.

What are the solutions?

Reversing decades of overfishing requires more effective enforcement of fishing regulations, especially the 80-km zone of no commercial fishing; vessel monitoring systems; a ban on the use of gill nets; and a prohibition on the catch of certain fish such as bluefin tuna.

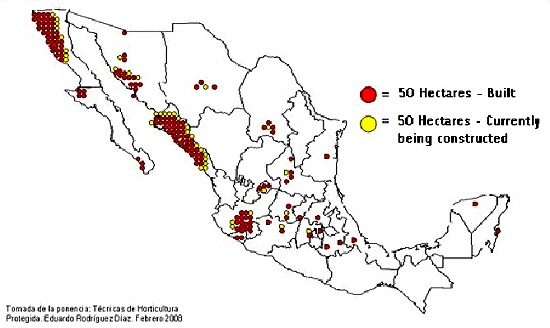

Fish farming may be a viable alternative and several commercial tuna farms, where wild tuna are raised in near-shore pens, have been established in Baja California but more research on the ecological pros and cons of establishing such farms is urgently needed.

In our next post, we will take a closer look at some recent research connected to the restoration of fish stocks in this region.

Fishing in Mexico is analyzed in chapter 15 of Geo-Mexico: the geography and dynamics of modern Mexico. Ask your library to buy a copy of this handy reference guide to all aspects of Mexico’s geography today! Better yet, order your own copy…