Twice a year, at the spring and fall equinox, the sun is positioned directly over the equator, giving everywhere on the planet twelve hours day and twelve hours night. The spring or vernal equinox, which heralds the start of spring, usually falls on 20 March or 21 March, and is celebrated in many parts of the world as a time of fertility and rebirth.

Mexico is no exception, and here are the nine most magical places in Mexico to celebrate the spring equinox:

1. Chichen Itza, Yucatán

The Mayan archaeological site of Chichen Itza, between Mérida and Cancún, is a very popular place to witness the spring equinox. The Kulkulkan temple is a masterpiece, built according to precise astronomical specifications. At the equinoxes, the sun=s rays in the late afternoon dance like a slithering snake down the steps of the pyramid. Spectators may not realize that this pyramid has amazing acoustical properties as well:

The astronomical observatory known as El Caracol (“The Snail”) at Chichen Itza has features aligned so precisely that they helped the Maya determine the precise dates of the two annual equinoxes.

2. Dzibilchaltún, Yucatán

Dzibilchaltún, in the state of Yucatán, about 20 km from Mérida, is much less well known but equally fascinating. The rays of the rising sun (spectators arrive before 5 am) light up the windows and entrances of the Temple of the Seven Dolls in a spectacular display.

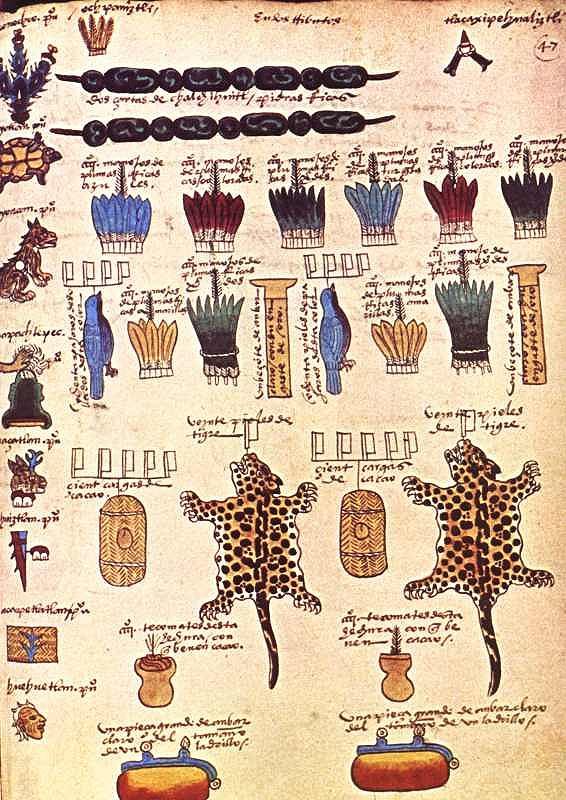

3. Great Temple, Mexico City

The Great Temple (Templo Mayor) in Mexico City marks the spot where legend says the Mexica priest Tenoch saw the promised sign of an eagle on a cactus indicating the original site for the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan. The city was renamed Mexico City when the Spanish conquistadors defeated the Aztecs and eventually became the largest city in the western hemisphere. As the sun rises at the Equinox, its rays shine precisely between the two major temples at this historic site. This spectacle, probably once reserved for the priests, can now be enjoyed by all.

4. Teotihuacan, State of México

Teotihuacan (“the city of the gods”) is the single most visited archaeological site in Mexico and an outstanding location to witness the spring equinox. Within easy day trip range of Mexico City, Teotihuacan was once a bustling city housing an estimated 200,000 people. It holds a special place in Mexico’s archaeological history since it was the first major site to be restored and opened to the public ~ in 1910, in time to celebrate the centenary of Father Miguel Hidalgo’s call for Independence.

The original inhabitants erected marker stones on nearby hillsides to mark the position of the rising sun at the spring equinox as viewed from the Pyramid of the Sun. Many of the visitors at the spring equinox today dress in white and climb to the top of the Pyramid of the Sun in order to receive the special energy of the equinox. There is some concern about the problems that so many spring revelers may cause:

5. Malinalco, State of Mexico

There is no direct evidence that the ancients celebrated the equinox at this location, though the archaeological site certainly has a carefully determined orientation. However, perhaps on account of its accessibility from Mexico City, Malinalco, in the State of México, has become a popular place to see in the spring.

6. Xochicalco, Morelos

Xochicalco, in the state of Morelos, is equally easy to reach from Mexico City and was the site of a very important calendar-related conference in the 8th century BC. It attracts equnox viewers on account of its considerable astronomical significance from pre-Hispanic times.

The site‘s main claim to archeo-astronomy fame is not connected to the equinoxes but to the two days when the sun is at its zenith (directly overhead) here each year, on 15 May and 28 July. The vertical north side of a 5‑meter‑long vertical “chimney” down into one particular underground cave ensures that the sunlight entering the cave on the day of the zenith is precisely vertical. The south side of the chimney slopes at an angle of 4o23′. Sunlight is exactly parallel to this side on June 21, the day of the Summer solstice.

7. Bernal, Querétaro

At the Spring Equinox, this town is invaded by visitors “dressed in long, white robes or gowns, and red neckerchiefs” who come seeking “wisdom, unity, energy and new beginnings”. (Loretta Scott Miller, in El Ojo del Lago, July 1997).

Since 1992, this Magic Town has held events each year from 19 to 21 March to celebrate the Spring Equinox. On 20 March, hundreds of people hike in the evening to the chapel of Santa Cruz, part-way up the Peña de Bernal, the giant monolith that overshadows the town, for hymns and prayers. They greet the sun as it rises on 21 March. Following a ceremony in the town square at noon (21 March), as many as 15,000 visitors form a human chain stretching from the plaza to the top of the monolith. Local attractions in Bernal include small museums about local history, masks and Mexico’s movie industry.

8. El Tajín, Veracruz

The amazing Pyramid of the Niches in El Tajín, Veracruz, is another great place to visit on the spring equinox. Crowds gather here to celebrate the equinox, despite the fact that in this location, there is no particular solar spectacle to observe. Today’s celebrations continue an age-old tradition at El Tajín, which has long been one of the most important ceremonial centers in this region.

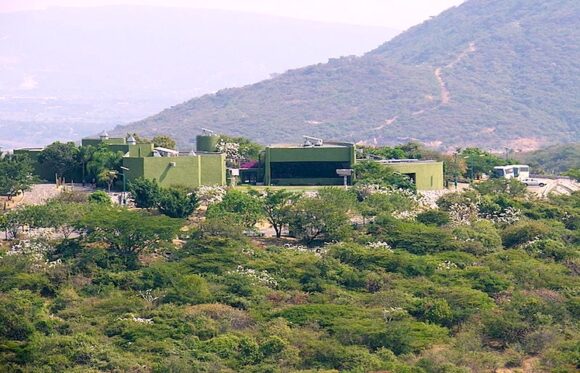

9. Monte Alban, Oaxaca

Monte Alban, just outside the city of Oaxaca, was the first planned urban center in the Americas, and was occupied continually for more than 1300 years, between 500 BC and AD 850. Visitors from all over the world, many of them dressed in white, converge on Monte Alban at the spring equinox to recharge their energy levels.

Magical Mexico!