Corn is one of the world’s major cereal crops and has long been a vitally-important crop to Mexico.

However, is it more efficient in energy terms to be a slash-and-burn farmer of corn in the jungle or a technologically-sophisticated corn farmer on the US or Canadian prairies?

David and Marcia Pimentel have compiled data from a variety of sources and analyzed this question and similar questions in some detail.

In Mexico, they calculated that about 1144 hours of human labor are required to produce 1 hectare (ha) of corn using only hand labor, and no animals or machinery. On the other hand, using machinery, cultivating a hectare of corn requires only 10 hours of labor in the USA.

The total energy required to cultivate a single hectare of corn by hand is 589,160 kcal for the 1144 hours of hand labor, plus 16,570 kcal for making the axe and hoe used by the farmer (this figure assumes a certain lifespan and maintenance needs for such tools), plus 36,608 kcal for the 10.4 kg of seed required. The grand total for energy inputs into the system is 642,336 kcal. [One kcal (kilocalorie) = 4184 joules.]

An average yield for corn in such a non-mechanized system is 1,944 kg/ha, equivalent to 6,901,200 kcal. The ratio between the energy output and the energy expended of this system is almost 11:1.

By way of comparison, the energy inputs (labor, machinery, gasoline, seeds, irrigation, herbicides, etc) in a typical, highly mechanized US or Canadian cornfield total 10,535,000 kcal/ha. The yield of corn is about 7,500 kg/ha, equivalent to 26,625,000 kcal. The energy ratio for this farming system is 2.5:1

More efficient than a tractor?

Which system is more efficient? This is where it becomes essential to define what is meant by efficiency. In terms of output per hour of labor, the US farm is far more efficient. In terms of yield per hectare, the US farm is more efficient. However, in terms of energy ratios, the Mexican farm is four times more efficient than its US counterpart.

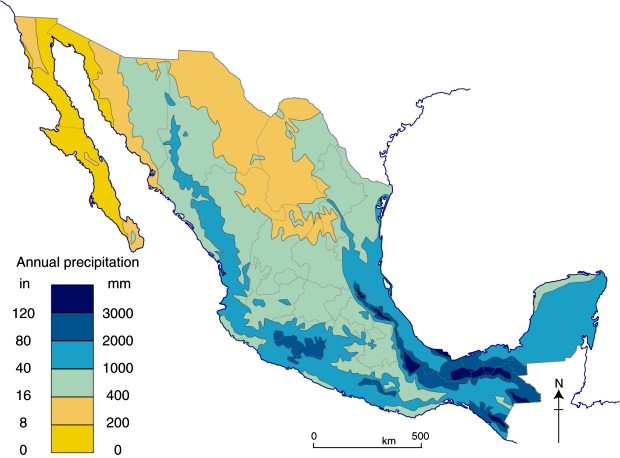

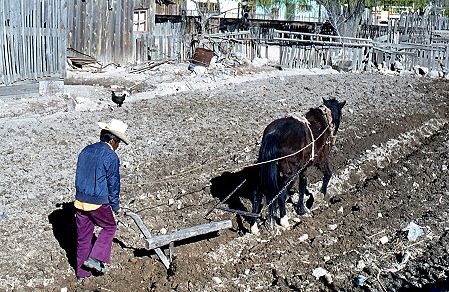

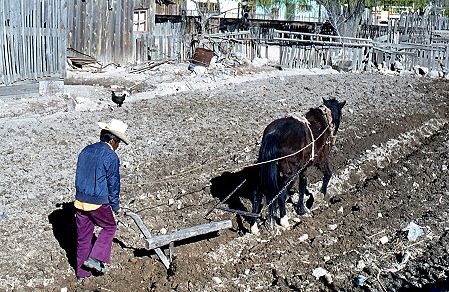

Looking at energy ratios makes it possible to make various generalizations about farming. In general, hand cultivation methods are the most energy efficient, followed by systems where animals are used, followed by systems based largely on machinery. The precise numbers for any type of farming will vary from one country to another, since the labor required and crop yields do depend to some extent on such geographic factors as soil types, terrain and the weather during the growing season.

It is also possible to look at what the additional energy inputs in a highly mechanized system actually achieve. For instance, in the USA, machinery and fuel account for about 20% of all the fossil energy employed; in other words, about 20% of the energy input reduces, or replaces, human and animal labor. The remaining 80% of fossil fuel inputs is employed in increasing corn yields by means of fertilizers, insecticides, herbicides and irrigation.

The table shows the energy ratios which have been calculated for a selection of crops in various countries.

| Type of farming | Location | Energy ratio (output/input) |

| Cassava | Tanzania | 23.0 |

| Corn (human power) | Mexico | 10.7 |

| Corn (human power) | Guatemala | 4,8 |

| Corn (oxen power) | Guatemala | 3.1 |

| Corn (oxen power) | Mexico | 4.3 |

| Corn (animal power) | Philippines | 5.1 |

| Corn (mechanized) | USA | 2.5 |

| Wheat (bullock power) | Uttar Pradesh, India | 1.0 |

| Wheat | USA | 2.0 |

| Rice (human power) | Borneo | 7.0 |

| Rice (mechanized) | Japan | 3.0 |

| Rice | California | 2.0 |

| Sorghum (human power) | Sudan | 14.0 |

| Sorghum | USA | 2.0 |

| Soybeans | USA | 4.0 |

| Oranges | Florida, USA | 2.0 |

| Apples | Eastern USA | 1.0 |

| Potatoes | New York state, USA | 1.2 |

| Potatoes | UK | 1.5 |

| Tomatoes | California | 0.6 |

| Spinach | USA | 0.2 |

| Eggs, battery | UK | 0.15 |

| Catfish | Louisiana, USA | 0.03 |

| Shrimp | Thailand | 0.01 |

| Oysters | Hawaii | 0.01 |

| Winter lettuce (glasshouse) | UK | 0.0023 |

| All agriculture, 1952 | UK | 0.47 |

| All agriculture, 1968 | UK | 0.35 |

| | |

An energy ratio below 1.0 for a particular item means that the inputs of energy exceed the output, or in other words more energy is expended on cultivation than is returned via the crop.

As Tim Bayliss-Smith concludes in the The ecology of agricultural systems, the evidence is that, “Only in fully industrialized societies does the use of energy become so profligate that very little more energy is gained from agriculture than is expended in its production.”

Why are energy ratios important?

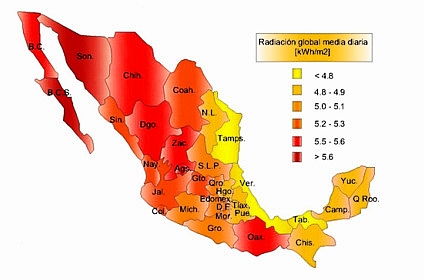

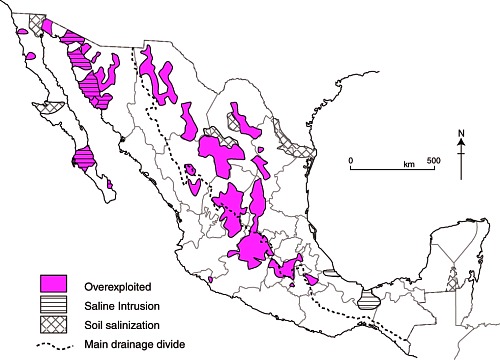

Energy ratios shed some light on the sustainability of farming. Cultivation relying only on human power, is clearly sustainable virtually indefinitely, provided that land degradation is avoided and yields do not decline. Farming using a mix of animal and human power is also likely to be fully sustainable. However, the same is not true for cultivation relying on power derived from fossil fuels. For mechanized farming, sustainability requires machinery to be powered by renewable sources of energy, such as solar or wind power. Such sources of energy may be impossible to harness in some climatic zones.

Of course, farm systems are not only about energy flows and ratios. As Tim Bayliss-Smith points out, farms ”also provide jobs, incomes and a way of life for agrarian societies, whose social and ideological characteristics cannot be ignored.”

Sources / further reading:

- Pimentel, David and Pimentel, Marcia H. Food, energy and society (3rd edition) CRC Press, 2008

- Bayliss-Smith, T.P. The ecology of agricultural systems. Cambridge University Press, 1982.

- Simmons, I.G. “Ecological-Functional Approaches to Agriculture in Geographical Contexts”, in Geography, 65: 305-316 (Nov. 1980)

Agriculture is analyzed in chapter 15 of Geo-Mexico: the geography and dynamics of modern Mexico. and concepts of sustainability are explored in chapters 19 and 30. Buy your copy today, so you have this handy reference guide to all aspects of Mexico’s geography available whenever you need it.