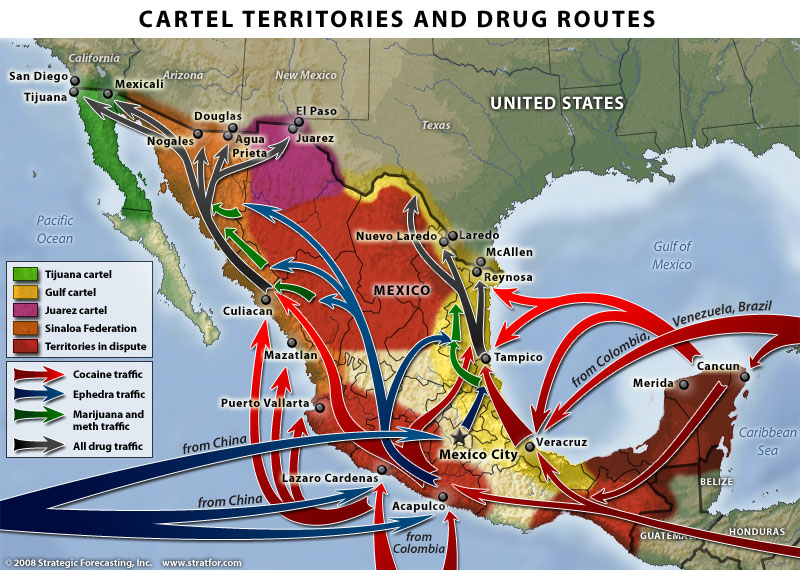

Drug trafficking is one of the North America’s major contemporary issues, with widespread ramifications not only for Mexico, but extending well beyond her national borders. This is the first of an occasional series of updates examining some of the numerous different effects of the war on drug-related violence on Mexican society, the environment and the economy.

How many members of Mexico’s military have lost their lives in the war against the cartels?

In “InSight Map: Counting Federal Casualties in Mexico”, Patrick Corcoran takes a look at the confusing statistics relating to the deaths of members of the military in Mexico. The number claimed by the government (470 federal forces killed since 2000) does not match any of the conflicting numbers released on separate occasions by the Defense Secretariat for the number of military personnel killed in the on-going war against the drug cartels.

Drug war violence has decreased press freedom in Mexico

Freedom House, in its annual report, says that Mexico has experienced one of the world’s most radical declines in press freedom. Mexico’s press is now categorized on the Press Freedom Index as “not free”, alongside press in Cuba, Honduras and Venezuela.

More than 60 journalists have been killed in Mexico in the last decade, including 10 in 2010. Many others have been kidnapped, or intimidated. Several journalists have sought asylum in the USA. Drug cartels have increasingly pressured local press and news stations to broadcast partisan material, regardless of its accuracy.

Earlier this year, several major media groups in Mexico agreed to de‑glorify drug trafficking by refusing to show any grisly photos or menacing messages. The pact has been heavily criticized in some sectors, however, mainly on the grounds that it downplays the gravity of the on-going violence.

New laws enacted to protect all migrants in Mexico

It is not only the USA that has problems coping with undocumented or unauthorized migrants. More than 300,000 immigrants pass through Mexico each year on their way from Central America to the USA. Mexico actively patrols its southern border to limit the number of Central Americans who succeed in reaching the interior of the country.

Now, a new federal law expressly recognizes and protects the human rights of all migrants in Mexico, regardless of their place of origin, nationality, gender, ethnicity, age and immigration status. The new law guarantees access to basic services such as health and education. It comes in the wake of the horrific discovery in northern Mexico in recent months of several mass graves of migrants, mainly originating from Central America. The graves are believed to be linked to people-trafficking operations, known to be a source of revenue for drug cartels.

Drug gangs and the price of limes

One unexpected by-product of Mexico’s on-going drug wars in January 2011 was a steep rise in the price of limes, a quintessential ingredient of Mexican food and drinks. Prices in Mexico City quadrupled to almost four dollars a kilo ($1.80 a pound).

The interesting story behind the sudden increase in lime prices is given by Nacha Cattan in The Christian Science Monitor. An accompanying graphic shows how drug traffickers intervened in the normal supply chain, “extorting farmers, attacking produce trucks, or causing more time‑consuming border inspections”.

Most of the limes sold during winter months come from the semi-tropical orchards around Apatzingán, a town in Michoacán, western Mexico. Local truckers have to pay drug gangs up to 800 pesos ($66) a truckload for safe passage. Thefts of fully-laden trucks rose 50% in some areas last year. Allegedly, the gangs also influence prices by limiting harvesting and restricting the operation of packing plants.

Fortunately for Mexican lime-lovers, the price of limes has since returned to normal, with drugs gangs switching their attention to the much more lucrative trade in avocados.

How long will drug-related violence in Mexico last?

Even the Public Security Secretary, Genaro García, has now stated publicly that Mexico’s war on drug cartels will not be over any time soon. He argues that Mexico’s campaign against the cartels is having success, but that organized crime and violence related to drug production and trafficking are unlikely to fall within the next seven years.

Previous posts about the geography of drug trafficking and drug cartels in Mexico:

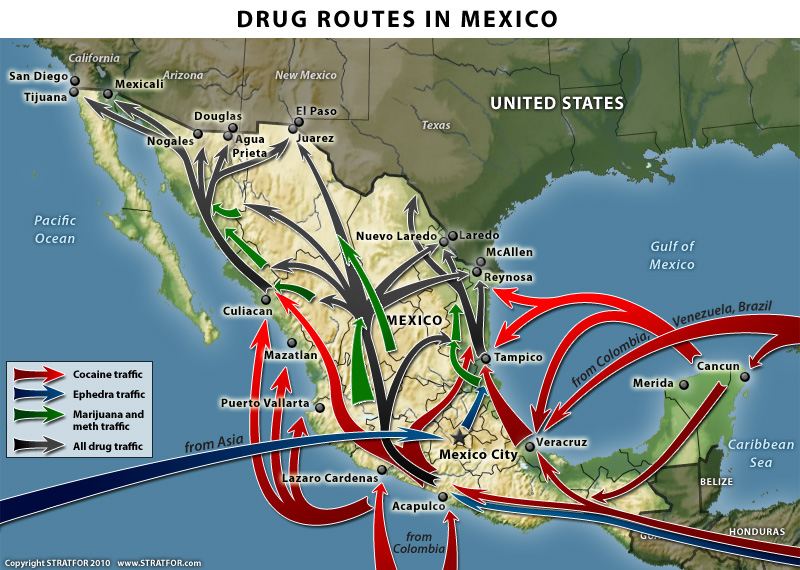

- The geography of drug trafficking in Mexico

- The background to Mexico’s fight against drug cartels

- Mexico’s export trade in drugs

- The economic benefits to Mexico of the drugs trade

- Mexican drug traffickers expand their influence to Central America

- Is drug war violence concentrated in Mexico’s largest cities?

- The rates of drug war deaths vary enormously in Mexico’s states

Geo-Mexico: the geography and dynamics of modern Mexico discusses drug trafficking in several chapters. A text box on page 148 looks at trends in the drug trafficking business and efforts to control it. Buy your copy today to have a handy reference guide to all major aspects of Mexico’s geography!