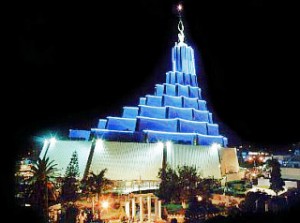

The map shows the percentage of the population of each state who profess themselves to be Catholic. Mexico’s population is predominantly Catholic but Mexican Catholicism is extremely varied in practice. It ranges from those who support traditional folk religious practices to those who adhere to the highly intellectualized liberation theology.

While the population remains predominantly Catholic, allegiance to the church has declined steadily since 1970. In 1970 96% of the population five years of age and older identified itself as Roman Catholic. By the 2010 census the figure had fallen to 84%. Though the proportion of Catholics is declining in Mexico, it is still considerably higher than in Mexico’s southern neighbors. For example, only about 70% in Guatemala are Catholic.

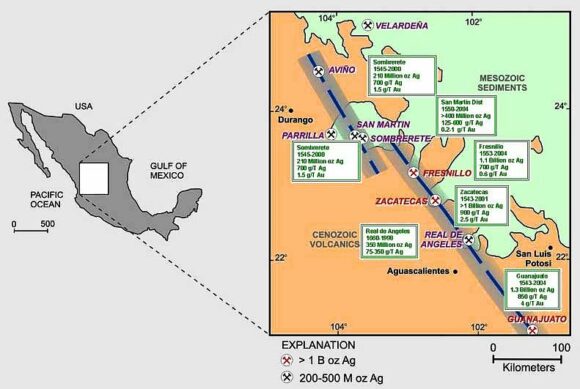

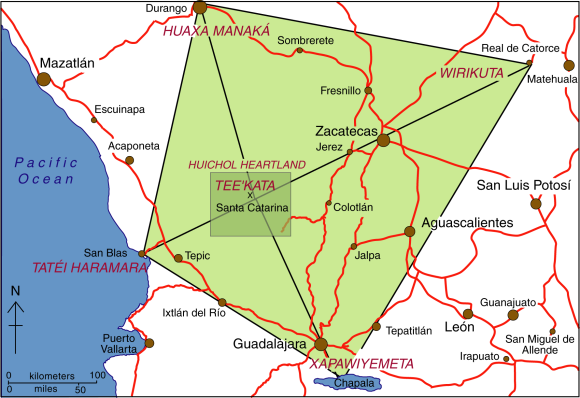

There are significant regional variations. Catholicism is strongest in a band of central-western states, extending from Zacatecas to Michoacán, where only one in twenty is not Catholic. In such areas, religion is a strong force in everyday life, with visible manifestations not only in the number of churches and other ecclesiastical buildings but also in the cultural importance and frequency of religious festivals and processions.

In contrast, about one in six is not Catholic in the northern border states. In southeastern Mexico (Chiapas, Campeche, Tabasco and Quintana Roo), about one in four is not Catholic. Interestingly, non-Catholics are concentrated in both the prosperous northern states and in the relatively poor south and southeastern states.

In summary, the pattern of Catholicism in Mexico exhibits a clear distance-decay pattern around the strongly-Catholic western states, with minor anomalies such as the state of Yucatán.

For more details, see these previous related posts:

- Easter celebrations in Mexico

- Western Mexico, Mexico’s Catholic heartland

- The decline of Catholicism in southern Mexico

- The growth of Protestant churches in Mexico

- The cultural geography of Mennonite enclaves in Mexico

The geography of Mexico’s religions is analyzed in chapter 11 of Geo-Mexico: the geography and dynamics of modern Mexico; many aspects of Mexico’s culture are discussed in chapter 13.