The latest United National Development Program (UNDP) report about the Human Development Index (HDI) in Mexico gives scores and ranks for each state. The full report, in Spanish, entitled “Índice de Desarrollo Humano para las entidades federativas, México 2015: Avance continuo, diferencias persistentes“, is readily available online, and is based on data up to and including 2012.

The HDI is a compound index based on several aspects of three major criteria: health, education and income.

HDI improved between 2008 and 2012 in all states except Baja California Sur. The greatest percentage increases in HDI were in Puebla (where HDI rose 3.7%), Chiapas (3.6%) and Campeche (3.6%). HDI in Baja California Sur fell 0.8%, mainly due to a lower score for education.

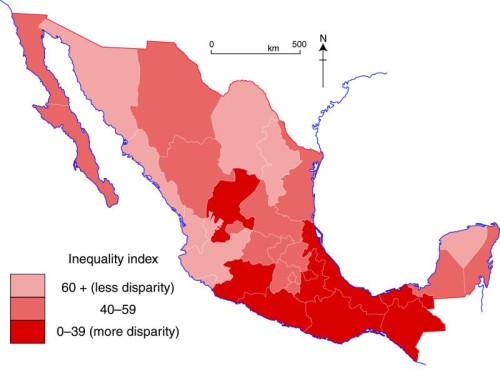

The pattern of HDI in Mexico, by state, is shown on the map. The highest HDI values in 2012 were for the Federal District with a score of 0.830, Nuevo León (0.790) and Sonora (0.779). At the other end of the spectrum, Chiapas had the lowest HDI (0.667), below Guerrero (0.679) and Oaxaca (0.681).

As noted previously on Geo-Mexico, the north-south divide in Mexico persists. In general, northern states, together with the Yucatán Peninsula states (Campeche, Yucatán and Quintana Roo) all have HDI values considered “medium” or higher, while southern Mexico (plus some other states, including Zacatecas, Guanajuato, Michoacán and Veracruz) all have “low” values.

The map includes international comparisons. For example, Oaxaca, one of most deprived states in Mexico, had a level of HDI in 2012 comparable to that of Botswana in Africa, even though that nation’s HDI is actually 38 positions below that of Mexico in the world rankings.

The report highlights the extent of disparities by calculating the number of years it will take each state, at the rates of change experienced from 2008 to 2012 to reach the HDI level of Mexico City. Interestingly, while it will apparently take Chihuahua 200 years to reach the HDI level of Mexico City, it will take Chiapas only 20 years to reach the same point.

The main conclusion that can be drawn is that the overall quality of life continues to improve in Mexico though not at equal rates throughout the country. Disparities persist and current patterns of public spending have failed to make significant inroads into diminishing these disparities. The UN report considers it a priority to close the development gaps in Mexico, especially in the two southern states of Chiapas and Oaxaca.